Over-loved modern – conserving Rose Seidler House

Once perceived as the ‘modern’ and most robust house in our collection, Rose Seidler House is now seen as quite possibly the most fragile.

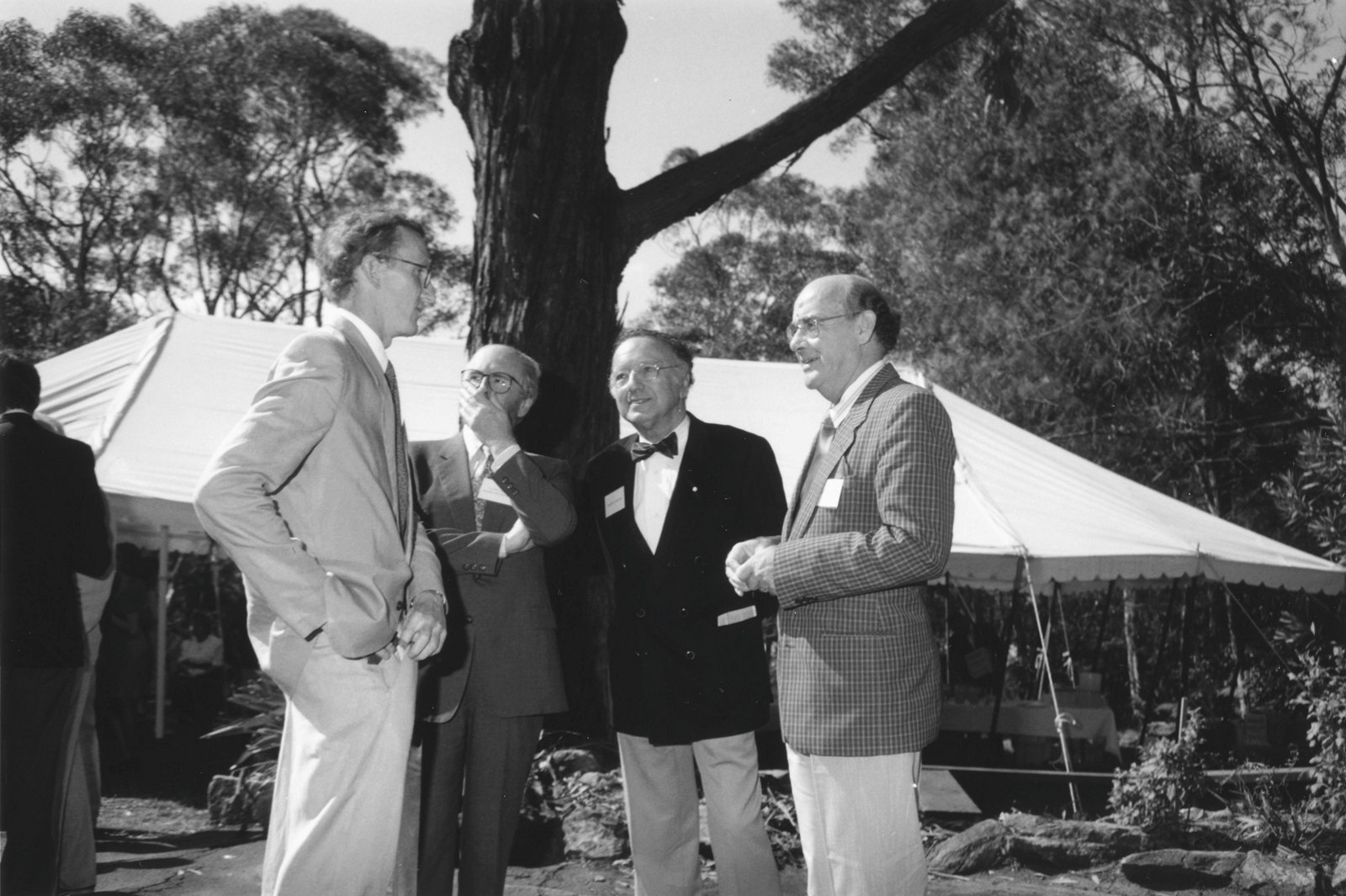

In July 2009 we hosted conference delegates from across the globe who met to discuss the issues confronting 20th-century buildings and landscapes at the (Un)loved Modern conference run by Australia ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites).

We were well placed to join this discussion given our role as custodian of Australia’s premier 20th century domestic icon, Rose Seidler House.

Our approach to the conservation of the house and collection has been guided in the most part by the original conservation management plan written in 1989, but has naturally evolved over the intervening period. The plan recognised that ‘it is easier to find an 1840s colonial oven than a 1940s Simpson electric stove’1 and that we lacked the craftspeople and materials to easily re-create or restore 1950s furnishings and finishes.

When architect Harry Seidler donated the house to the then HHT (Historic Houses Trust), a formal agreement bound us to maintain the property ‘as designed in 1949 and as fully restored in 1982’.2 This was to be a modern house museum, the first in Australia, with an implied durability and ability to provide wide-ranging opportunities for open visitation, study groups, lectures, concerts, exhibitions, filming, photography, commercial functions and other events. After 18 years of a 'hands-on' approach to public access (the house was opened to the public for the first time in 1991), it has become clear that the public, the environment (chiefly light and heat) and our own activities, such as holding functions and moving objects around, have had an impact on the house and its collection.

Moreover, the 'Simpson stove scenario' is compounded by the distance we now have from the HHT's original decisions about the property and a changing environment that makes it more difficult to embark once again on some of the ambitious re-creations and acquisitions that, under the guidance of the conservation management plan, were carried out in the late 1980s. Over the past 18 years there has been a growing realisation that Rose Seidler House and its unique 20th-century collection are very fragile. Re-created and genuine 'prop' objects obtained to represent items that were known to exist in the house are themselves now so rare that they warrant their own conservation plans and collection policy. Fabrics, carpets and paint finishes are now so difficult to re-create that we must re-evaluate the amount of wear and tear they sustain. As the 'modern' house itself ages, the natural desire of a heritage organisation to preserve original fabric is increasingly at odds with our commitment to showcase the property in its 1950s appearance and condition. In 2008 we formed a curatorial advisory panel to bring together different views and expertise from within the organisation to develop a strategy of care and interpretation for Rose Seidler House for the next 20 years. The panel commissioned a comprehensive assessment of the collection and provided a revised set of guidelines for our care and management of the property into the future. The changes reflect our realisation that we must have effective control over public access and be able to protect the house and contents from possible damage caused by light and heat. We must be proactive in caring for and maintaining the collection. Critically, to satisfy the terms of the original agreement and to maintain the 'significance' of the whole, we may, in the future, when all in situ conservation strategies have been exhausted, need to consider retiring objects from display and replacing items in the collection. The 'significance' of Rose Seidler House has changed dramatically in 20 years and will almost certainly continue to change in the future. A theme of the (Un)loved Modern conference was 'the single house under threat'. Given today's demand for ever larger houses, the modest dimensions of mid-20th-century houses make them particularly vulnerable to demolition and renovation. Outstanding examples such as Rose Seidler House are increasingly valuable, as they demonstrate the aesthetic and functional potential of small houses and offer an ongoing challenge to current trends. Rose Seidler House is not just an evolving museum. It is an international architectural icon that requires its own set of principles that may at times appear to be at odds with our preconceptions of standard museum and conservation practice.

Notes

1. Peter Emmett, Mid century modern: Rose Seidler House conservation management plan, November 1989

2. International Conservation Services, Rose Seidler House: Conservation assessment of furniture and fixed fittings, October 2008

Published on

Related

Browse all

Conserving Harry Seidler’s sofa

A sofa Harry Seidler designed for Rose Seidler House was conserved and reupholstered, and the process revealed some unexpected findings

Eulogy Harry Seidler AC OBE 1923-2006

This is an edited version of a eulogy given by Peter Watts at Harry Seidler's Memorial Service at the Theatre Royal, Sydney, 6 April 2006

Cook & Curator

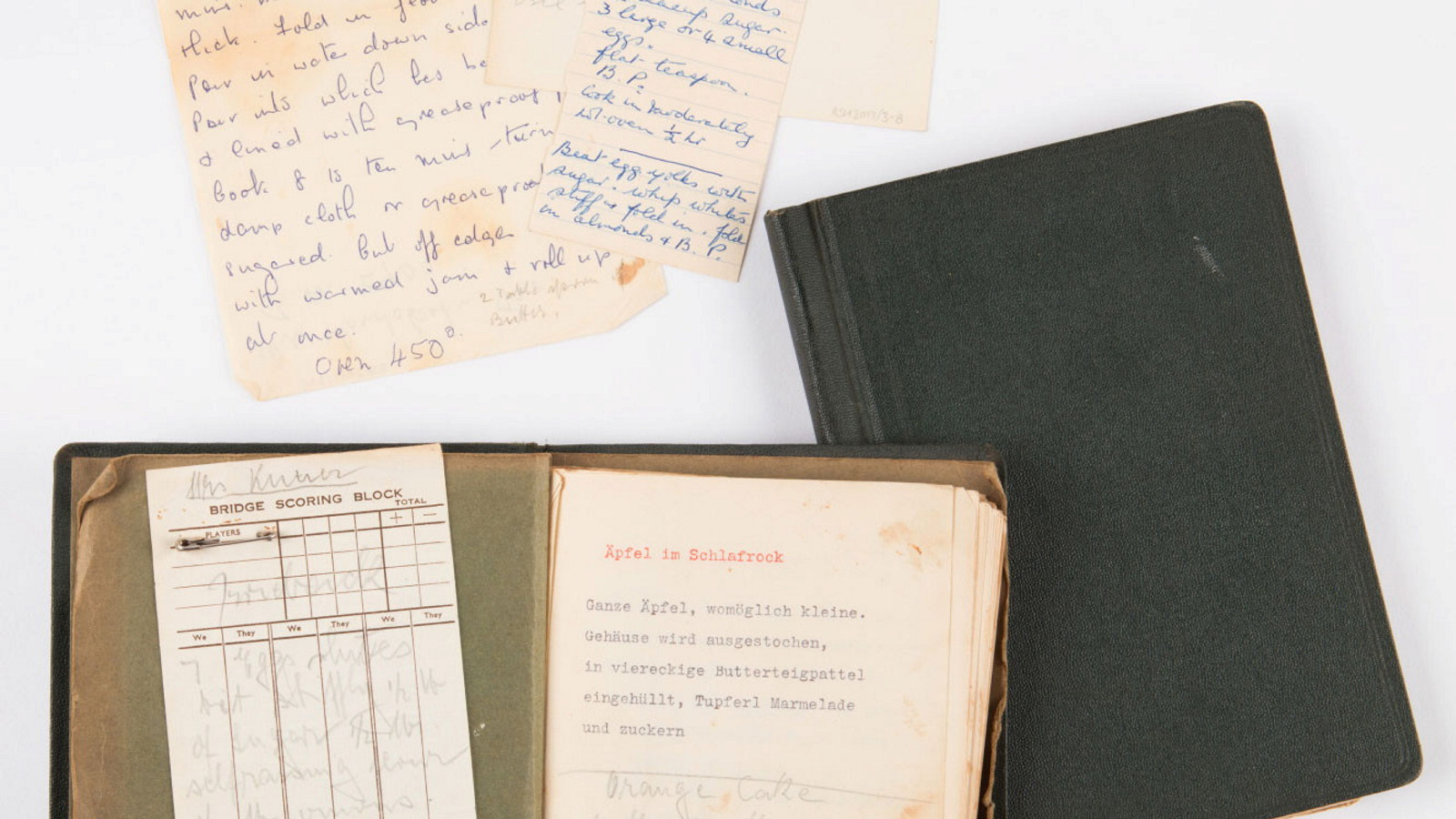

Translating tastes: the Rose Seidler recipe collection

Recently translated from the original German, recipes kept by Rose Seidler provide valuable insight into her culinary heritage and Austrian identity

Cook & Curator

Eier auf Florentiner Art (Eggs Florentine)

This classic recipe is simple to make yet rich and flavoursome. Perfect for a weekend brunch or a light supper