Alexander Riley, legendary Aboriginal police tracker

The remarkable talents of Aboriginal trackers who worked for NSW Police in the 20th century are featured in a display at the Justice & Police Museum. Accompanied by collection items, the centrepiece of the display is the documentary Black tracker, exploring the life of Tracker Alec Riley.

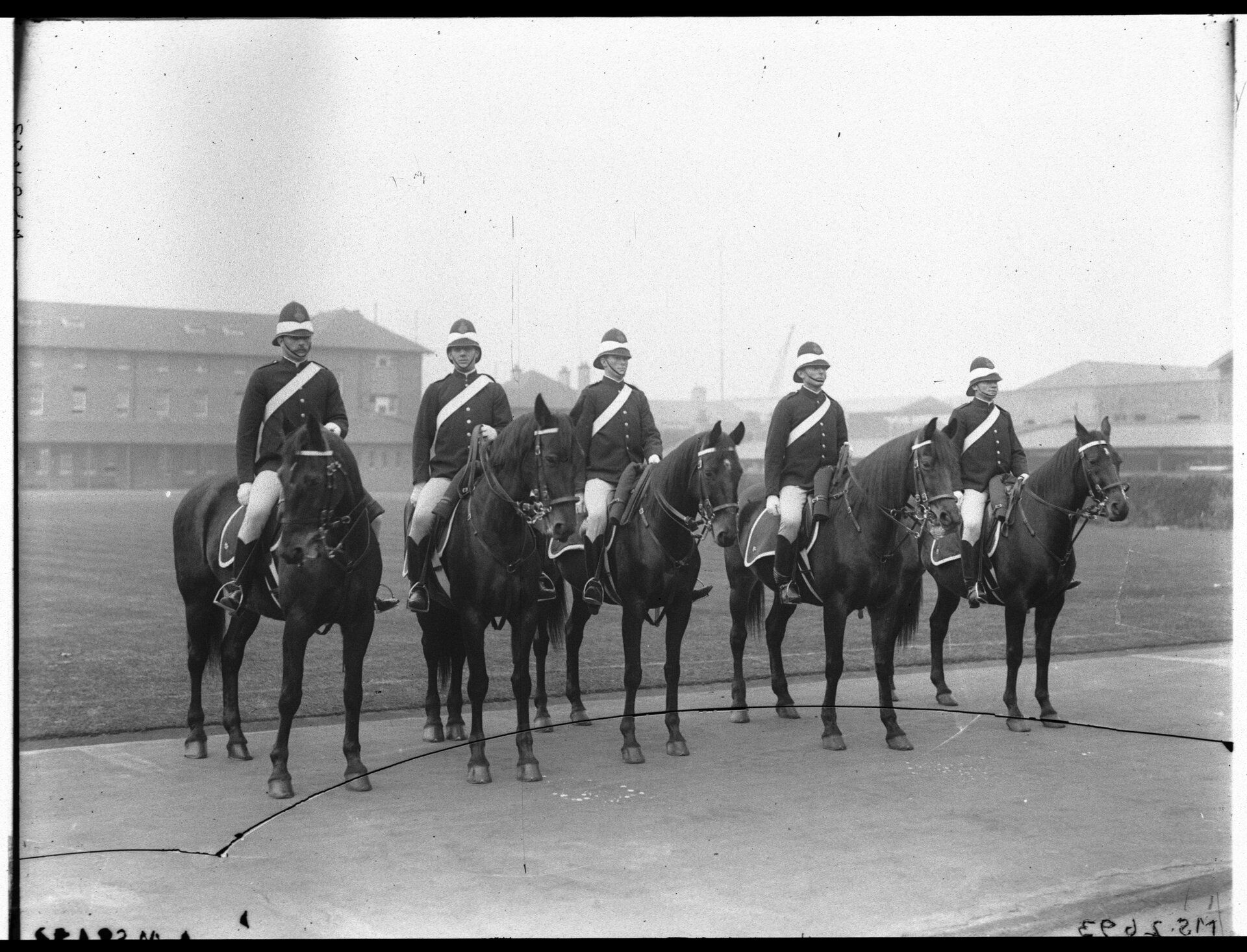

From the earliest days of the NSW colony, the authorities saw First Nations people’s deep understanding of Country as useful to help search for criminals on the run, stolen property, and people and livestock lost in the bush. These early trackers don’t appear to have been employees but were hired for specific search parties. However, when the centralised NSW Police Force was established in 1862, trackers were listed as a police role, and police returns the following year show that around 30 trackers were employed.

Alexander ‘Alec’ Riley (1884–1970) joined NSW Police as a tracker in 1911. For nearly 40 years until his retirement in 1950, he served in the Western District around Dubbo in central northern NSW, on Wiradjuri Country. With his highly regarded skills, he was also called on to assist searches in other parts of NSW, as well as Queensland and Victoria.

Riley was the first tracker to attain the rank of sergeant, in 1941, and two years later he was awarded the King’s Police and Fire Service Medal for distinguished service. However, his retirement drew attention to the unequal status of trackers in NSW. Like female police officers, trackers were designated as ‘special constables’, which meant that they were not entitled to receive a police pension. Although Riley was a deeply private man, his supporters campaigned against this injustice, taking his case all the way to the NSW Parliament, without success.

Riley remained living with his family on the Talbragar Aboriginal Reserve near Dubbo, where he continued his lifelong sporting interests, including coaching athletes. He died in 1970.

High-profile cases

Two high-profile cases Riley investigated during his long career were the Narromine Murders, and the disappearance of Desmond Clark.

In 1939, labourer Albert Andrew Moss was arrested on suspicion of killing three men near Narromine, a town 40 kilometres west of Dubbo. At Moss’s trial, a witness testified that Moss claimed he had killed a ‘baker’s dozen’ (13 people), but this number was never proven. It was Riley who had tracked the path of a stolen horse-drawn sulky belonging to one of the victims and found human remains in a campfire. Thanks to this evidence, Moss was found guilty and spent the rest of his life in prison.

A year later, in December 1940, two-year-old Desmond Clark wandered away from his grandparents’ farmhouse in Bugaldie, north of Dubbo. Joining the large search two weeks later, Riley believed that the searchers were looking in the wrong place. The search team rejected his theory, insisting the boy must have wandered into the thick scrub. Eight months later, with Desmond still missing, Riley was sadly proven correct when he returned to the farm and found the boy’s remains in a creek bed where he had predicted.

This case was the subject of a 2001 feature film, One night the moon, directed by Rachel Perkins. It was the second time Riley had inspired a filmmaker: in 1996, his grandson Michael Riley made the documentary Black tracker about his grandfather’s life. This film forms part of the Justice & Police Museum display.

Trackers in the archives

The resources of the NSW State Archives Collection are invaluable for researching trackers’ careers. Historian Michael Bennett gives an insight into what the archives hold in his video presentation Aboriginal trackers, a useful starting point for anyone interested in exploring the topic further. The archives also provide a helpful guide to navigating the records relating to NSW Police personnel, including trackers.

A wealth of information can be found in documents such as police pay records and service cards. For example, Riley’s pay record shows his mid-1911 start date with NSW Police in Dubbo and his pay grade. A police officer’s career, including any transfers, can be traced through registers such as this.

Riley’s service card reveals more personal details. The first page lists physical characteristics: height, and hair and eye colour. Any previous careers are noted along with birthplace and marriage status. Career promotions, qualifications, commendations and retirement date are also recorded. If Riley had been issued any special equipment, it would also be included here.

The last of the NSW Police trackers, Norman Walford, retired in 1973. Although it is no longer a designated NSW Police role, the story of the trackers and their remarkable skills lives on, waiting to be found in the State Archives Collection.

Visit the display

Permanent display

Alexander Riley, legendary Aboriginal police tracker

The remarkable talents of Aboriginal trackers who worked for NSW Police in the 20th century are featured in a display at the Justice & Police Museum

Monday 18 September

Published on

Related

Police service guide

The first police force in the Colony was made up of eight of the best-behaved convicts. This guide provides information for researching police officers in NSW

Aboriginal trackers & gaol photos

This webinar highlights records that Aboriginal people can access to discover more about their own family history on the colonial frontier