Convicts and scorbutus at the General ‘Rum’ Hospital

Convicts who were lucky enough to survive the transportation voyage, often arrived at Sydney Cove suffering infectious disease or other illness, and were admitted directly to the colony’s General 'Rum' Hospital.

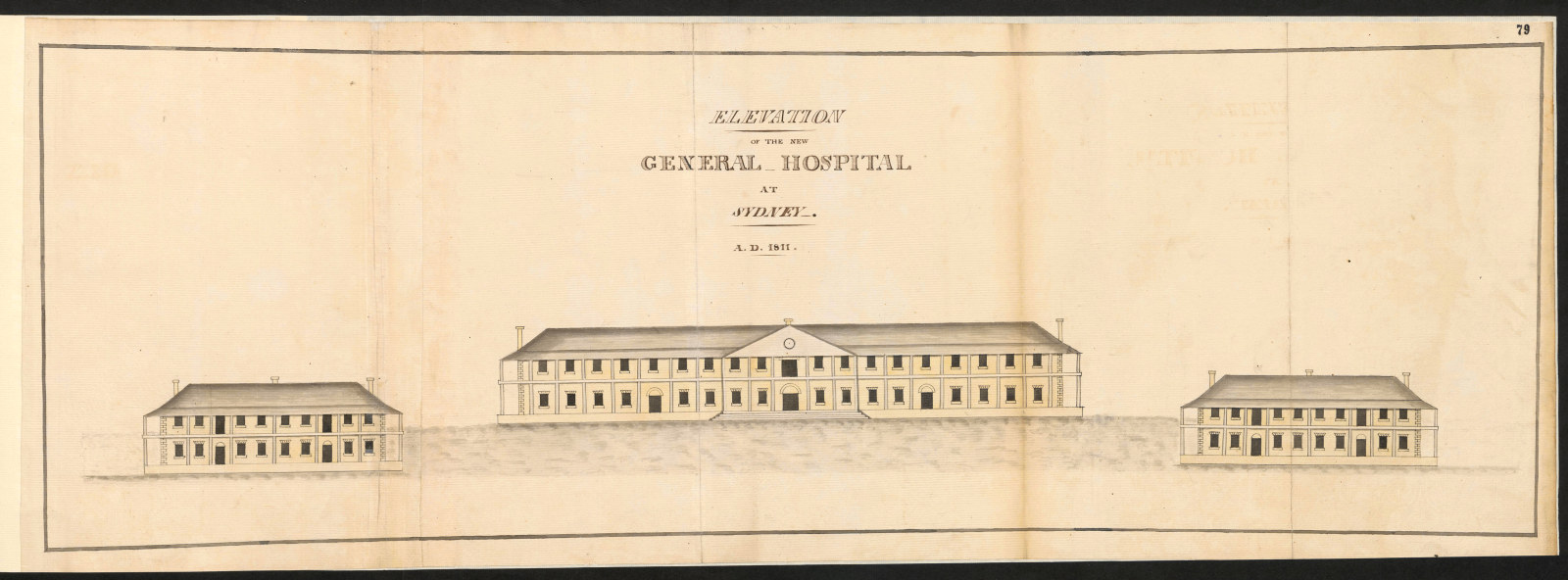

Despite observations about shipboard hygiene and disease prevention made by Captain Cook in the late eighteenth century, convicts on the transport ships sailing to New South Wales continued to die from preventable diseases. It has been calculated that between 1795 and 1801, one convict in ten died during the transportation voyages.1 Convicts who were lucky enough to survive the transportation voyage, but arrived at Sydney Cove suffering disease, were admitted directly to the colony’s General Hospital. After the opening of the three-winged General ‘Rum’ Hospital on Macquarie Street in 1816, ill convicts were admitted to the central building, where the wards were sometimes overcrowded with patients suffering the illness referred to at the time as scorbutus (scurvy). The central building is now long gone, but the south wing where the surgeons lived survives today as The Mint, and the north wing as Parliament House.

We now know that scurvy is caused by a vitamin C deficiency, and while it was known by at least 1753 that scurvy could be treated with citrus fruit,2 the introduction of a daily ounce of lemon or lime juice to the convict shipboard rations did not entirely prevent the disease. Scurvy was a major contributing factor to convict death rates throughout the transportation era. It was not just convicts who suffered scurvy – it was commonly suffered by sailors for centuries, and it is thought that scurvy has caused more human suffering throughout history than any other nutritional deficiency disease.3

Surgeon William Redfern was appointed to the hospital to provide medical care for the convict patients, and he moved in to his quarters in the south wing (now The Mint) with his wife Sarah in 1816. Redfern was the colony’s expert in the prevention of disease on board convict ships, having been appointed two years before to investigate the huge losses of life on board the convict transport ships Surry, General Hewitt and Three Bees. Redfern proposed fundamental changes to ventilation, cleanliness, fumigation, diet and clothing, provision of water and wine, allowing convicts on deck, and the employment of competent surgeons with independent authority over the convicts on board.4 With these measures in place from 1814, there were far fewer convict deaths on subsequent voyages,5 and Redfern’s report is now considered the greatest administrative development in the history of convict transportation.6

Shipboard conditions were greatly improved and mortality was reduced, but there were still plenty of newly arrived convicts that required medical care at the Rum Hospital. Convicts with scurvy accommodated in the wards would have suffered weakness, fatigue, bleeding gums, loose teeth, bad breath, diarrhoea, dysentery, stiffness in the joints, and blackening of the skin.

In January 1829, The Australian reported that sixteen prisoners suffering scurvy from a ship in the harbour were ‘brought on shore, and conveyed in carts along the streets to the General Hospital’.7 When the Ocean arrived (1823), forty convicts suffering scurvy were admitted directly to the hospital, and from the Earl St Vincent (1823) there were 192 cases, but only one death. By far the worst outbreak of scurvy was on the Lord Lyndoch in 1838, with 128 cases of scurvy.8 Eight died from scurvy during the voyage and on arrival in Sydney, 113 were taken directly to the General Hospital, where a further 20 died.9 With the care of the surgeons and staff however, and the more varied diet available on land, many scurvy sufferers at the Rum Hospital would have recovered within weeks. Governor Gipps stated however, that those convicts discharged from the hospital would ‘feel the effects of the disease for the rest of their lives’.10

Notes

1. Edward Ford, The Life and Work of William Redfern: the Annual Post-Graduate Oration (Sydney: Australasian Medical Pub. Co., 1953), p15.

2. James Lind, A Treatise on the Scurvy (London: A. Millar, 1753).

3. K.J. Carpenter, The History of Scurvy and Vitamin C (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

4. Redfern’s report enclosed in the despatch between Governor Macquarie and the Commissioners of the Transport Board, 1 October 1814, HRA Series 1, Volume 8, pp274-292.

5. J. McDonald and R. Shlomowitz, ‘Mortality on Convict Voyages to Australia, 1788-1868’, Social Science History, 13, 1989, pp285-313.

6. Brian Gandevia, Tears Often Shed: Child Health and Welfare in NSW from 1788 (Sydney, 1978), p16.

7. The Australian, 20 January 1829, p4.

8. Mark Staniforth, ‘Deficiency Disorder: Evidence of the occurrence of scurvy on convict and emigrant ships to Australia, 1837-1839’, The Great Circle 13(2), 1991, pp119-132.

9. Charles Bateson, The Convict Ships, 1787-1868 (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1983), p269.

10. Gipps to Glenelg, 8 March 1839, HRA series 1, Volume 20, p57.

Related

What was the ‘Rum’ Hospital?

Between 1816 and 1848, the General Hospital on Sydney’s Macquarie Street, provided medical care for the colony’s convict workforce

Published on

Related

Browse all

Convict Sydney

James Hardy Vaux

Some convicts were transported more than once. Vaux was sent to the colony three times, each time arriving under a different name

Convict Sydney

Pick of the crop

Convicts could earn good money doing private work, so many tried to conceal their skills during the initial muster to avoid being assigned to government projects

Convict turned constable

A recently donated letter, signed by the governor of NSW in 1832, offers a tangible connection to the story of Samuel Horne, a convict who rose to the rank of district chief constable in the NSW Police

Cultivating a therapeutic landscape

Tracing the evolution of the Parramatta Female Factory to a hospital