Tom and Fowler

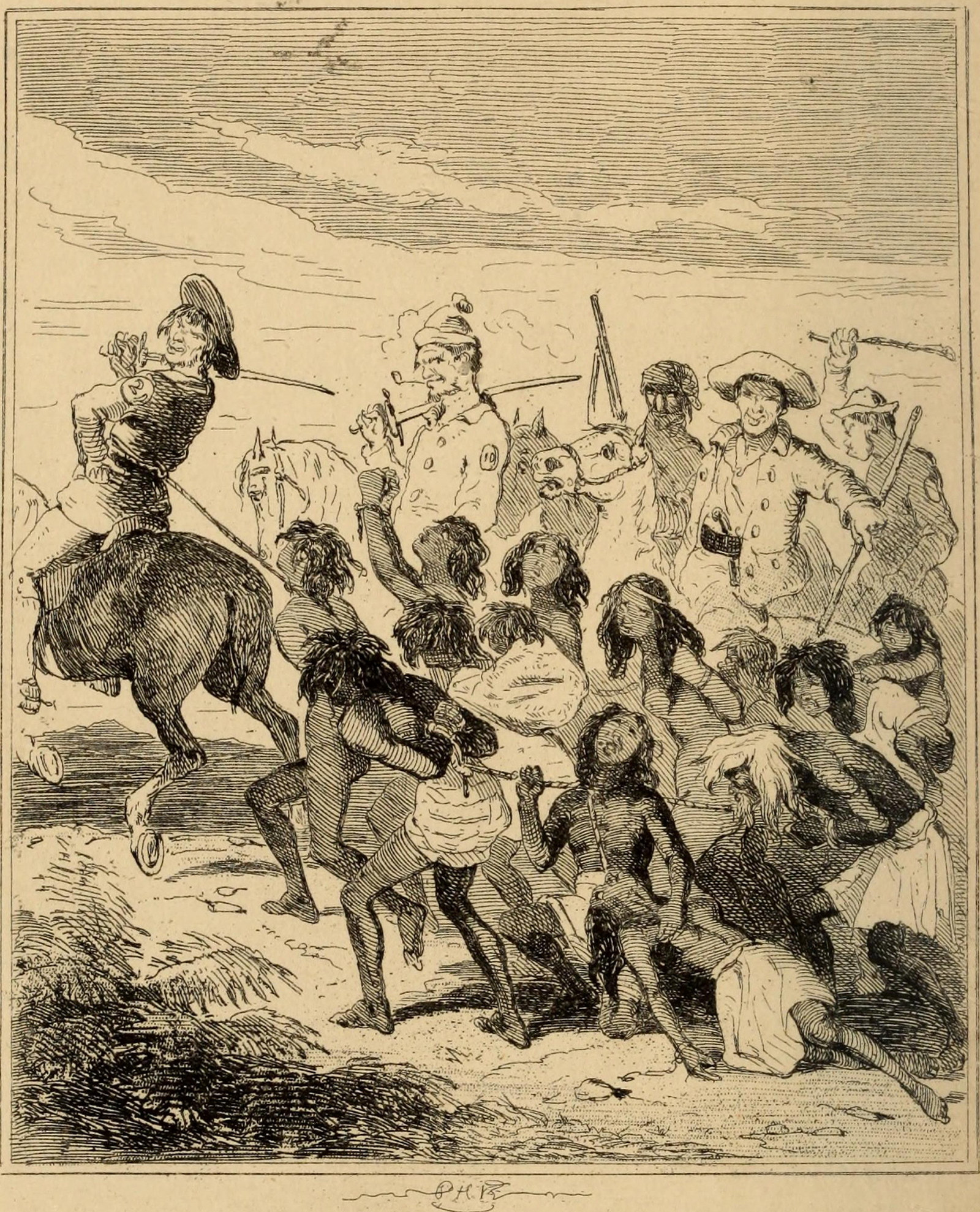

On 4 May 1843, Fowler and fifteen other Aboriginal men broke into watchman Patrick Carroll’s hut near the McLeay River, 107 miles from Port Macquarie.

The shepherds who shared the hut were out working at the time. Carroll offered the intruders sugar, flour, and tea. This failed to appease them and a couple of the men, including Fowler, hit Carroll with their tomahawks. As Carroll fled the hut, he was hotly pursued. One of the men slashed at the fleeing shepherd. As Carroll raised his hands to protect his head, the tomahawk cut his hand and throat. He then fell to the ground and feigned death. Eventually, his dog came up and stood over him, howling, at which point he realised the Aboriginal men had gone.1

Carroll took six weeks to recover. Meanwhile Commissioner of Crown Lands Robert Massey Esq. issued arrest warrants for several of the men and eventually, with trooper James Smith, located Fowler on 30 May. They found a waistcoat in his possession that Carroll later identified as his own. Fowler was gaoled to await trial on a charge of being present and aiding and abetting the wounding of Patrick Carroll with intent to kill him.2 The following month, the Maitland Mercury referred to the ongoing ‘serious depredations’ in the district and mentioned how several of ‘the most notorious’ Aboriginal men were recently captured. Three Aboriginal men were rumoured to have been shot in the affray preceding the arrests. Fowler was mentioned by name, and described as ‘a desperate character, supposed to have been concerned in some murders at Gogo [sic] some years back’.3

Fowler was one of three Aboriginal defendants brought before Justice Alfred Stephen at the Maitland circuit court on Friday 15 September 1843 in relation to Carroll. After hearing the evidence, Stephen ‘highly complimented’ Massey ‘on the promptitude which he had exhibited in the apprehension of the prisoners’.4 Such an observation from the judge could have left no room for doubt in the minds of the jurymen as to the verdict Stephen was anticipating. Unsurprisingly the jury immediately returned a guilty verdict. When this was interpreted to the prisoners they all denied that they had committed any offence. Stephen sentenced the defendants, including Fowler, to death. He claimed that hanging provided the ‘most humane course which (sic) could be adopted both towards the blacks, and towards the unprotected stockmen and shepherds’. He pointed to the ‘necessity of making examples of them’.5

At the same Maitland circuit court sitting an Aboriginal man known as Tom or Kambago appeared before Stephen to answer a charge of ‘wounding William Vant in the back with a spear, with intent to kill him, on the 24th of April last, at Durrundurra’. Defence counsel W A Purefoy argued that under the statute 1 Victoria, c.85, s.2 Tom was entitled to be acquitted as the law required the wound to be shown to have been dangerous to life. He claimed that the evidence tendered to the court did not show that to have been so in this case. Stephen would not entertain Purefoy’s argument, and nor would he allow the point to be decided by the jury. Instead, he overruled Purefoy’s objection and claimed that if the wound was inflicted by the prisoner with the intent to kill, regardless of whether or not the wound was dangerous to the victim’s life, then that was sufficient to constitute a capital offence. It took the jury only a few minutes to find Tom guilty. True to form, Stephen sentenced him to death. Tom responded through his interpreter that he ‘did not do it – white people told lies’.6

Eventually the Governor and his Executive Council rescinded the death sentences imposed on Fowler, Tom, and two other Aboriginal defendants from the same Maitland circuit court hearings. The men were instead sentenced to transportation.7 Fowler and Tom were amongst a group of prisoners who arrived at the penal station on Cockatoo Island in Sydney Harbour on 1 November 1843. They remained there until 17 April the following year. They were then sent to Darlinghurst Gaol before being put on board the Governor Phillip to be transported to the penal station at Norfolk Island.8

Fowler and Tom spent two years on Norfolk Island before being relocated to Van Diemen’s Land as the second penal station at Norfolk Island was gradually being closed down.9 The administration of Norfolk Island officially shifted from New South Wales to Van Diemen’s Land on 29 September 1844.10 As part of the preparations for this transfer and the relocation of convicts, a register was compiled in August 1844 of all the convicts sent to Norfolk Island from New South Wales.11 Fowler’s and Tom’s names appear on this register alongside several other Aboriginal convicts. The men arrived in Hobart Town on the Lady Franklin on 19 June 1846.12 They were sent to join a work gang at Darlington probation station on Maria Island.

The following month, July 1846, Fowler and Tom were sent back to the Prisoners’ Barracks in Hobart, then returned to New South Wales on the brig Louisa.13 After a brief stay at Hyde Park Barracks, where they were authorised to receive rations, Fowler and Tom were to be sent back to their respective districts.14 On 28 September 1846, the Principal Superintendent of Convicts was informed by the Colonial Secretary’s Office that approval had been granted for their return to Port Macquarie and Moreton Bay respectively ‘at an expense not exceeding two pounds fifteen shillings, to be defrayed out of Colonial Funds’.15 These two men were a couple of just a handful of Aboriginal convicts who lived long enough in custody to be able to return home.

Notes

1. Maitland Mercury, 16 September 1843, 2-3.

2. Maitland Mercury, 16 September 1843, 2-3.

3. Maitland Mercury, 17 June 1843, 4.

4. Maitland Mercury, 16 September 1843, 2-3.

5. Maitland Mercury, 16 September 1843, 2-3.

6. Maitland Mercury, 16 September 1843, 2-3.

7. Maitland Mercury, 14 October 1843, 3.

8. ‘A Return Shewing the Number of Aboriginal Blacks Who Have Been Received on Cockatoo Island From the 1st of January 1839 to the 16th December 1850’, 28 December 1850, 50/12485 4/3379, State Archives and Records New South Wales (SARNSW).

9. Gipps to Stanley, 23 February 1844, Historical Records of Australia (HRA), Series I, Volume XXIII, 418.

10. Stanley to Gipps, 10 November 1843, HRA, Series I, Volume XXIII, 215.

11. Alphabetical Register of Convicts Secondarily Transported from New South Wales to Norfolk Island and Remaining There in August 1844, CON 148, Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office (TAHO).

12. CON 17/1, 176-177, TAHO.

13. CON 37/3, 669-670,TAHO; CUS 36/1/347, TAHO.

14. Colonial Secretary to the Principal Superintendent of Convicts, 21 September 1846, Reel 1054, 4/3692, p. 175, SARNSW.

15. Colonial Secretary to the Principal Superintendent of Convicts, 28 September 1846, Reel 1054, 4/3692, p. 178, SARNSW.

Published on

First Nations stories from Convict Sydney

Browse all

Convict Sydney

Myall Creek massacre

On Sunday 10 June 1838, at least 28 Aboriginal people were massacred by a group of 12 Europeans at Myall Creek Station

Convict Sydney

Duall

When Duall was born in the mid-1790s conflict over resources and competing land use practices in districts surrounding Sydney was giving rise to tensions between the original inhabitants of the land and the newcomers

Convict Sydney

William Dawes

Officer of marines, scientist, astronomer, engineer, surveyor, teacher and administrator

Convict Sydney

Murphy

‘Murphy’ was one of a few Aboriginal men who tragically found themselves trapped in the British convict system