Duall

When Duall was born in the mid-1790s conflict over resources and competing land use practices in districts surrounding Sydney was giving rise to tensions between the original inhabitants of the land and the newcomers.1

Duall frequented a bountiful inland plain that the British called the Cowpastures, an area used as both hunting ground and meeting place by Dharawal, Darug, and Gundungurra people. He entered the colonial record in 1814 as an expedition guide taking seventeen-year old Hamilton Hume on the latter’s first exploratory journey south of the Cowpastures to Berrima.2 By the time the youths returned, the colony was in the grip of ‘Very Extraordinary and Unprecedented Droughts’ that continued until March 1816.3 The already stressed Districts of Airds and Appin, adjacent to and including the Cowpastures, came under increasing strain from an influx of settlers that displaced Aboriginal people and put pressure on existing resources.4 Tensions escalated. In 1814, Governor Lachlan Macquarie ordered a punitive expedition against Aboriginal people at the Cowpastures, yet this failed to restore peace.

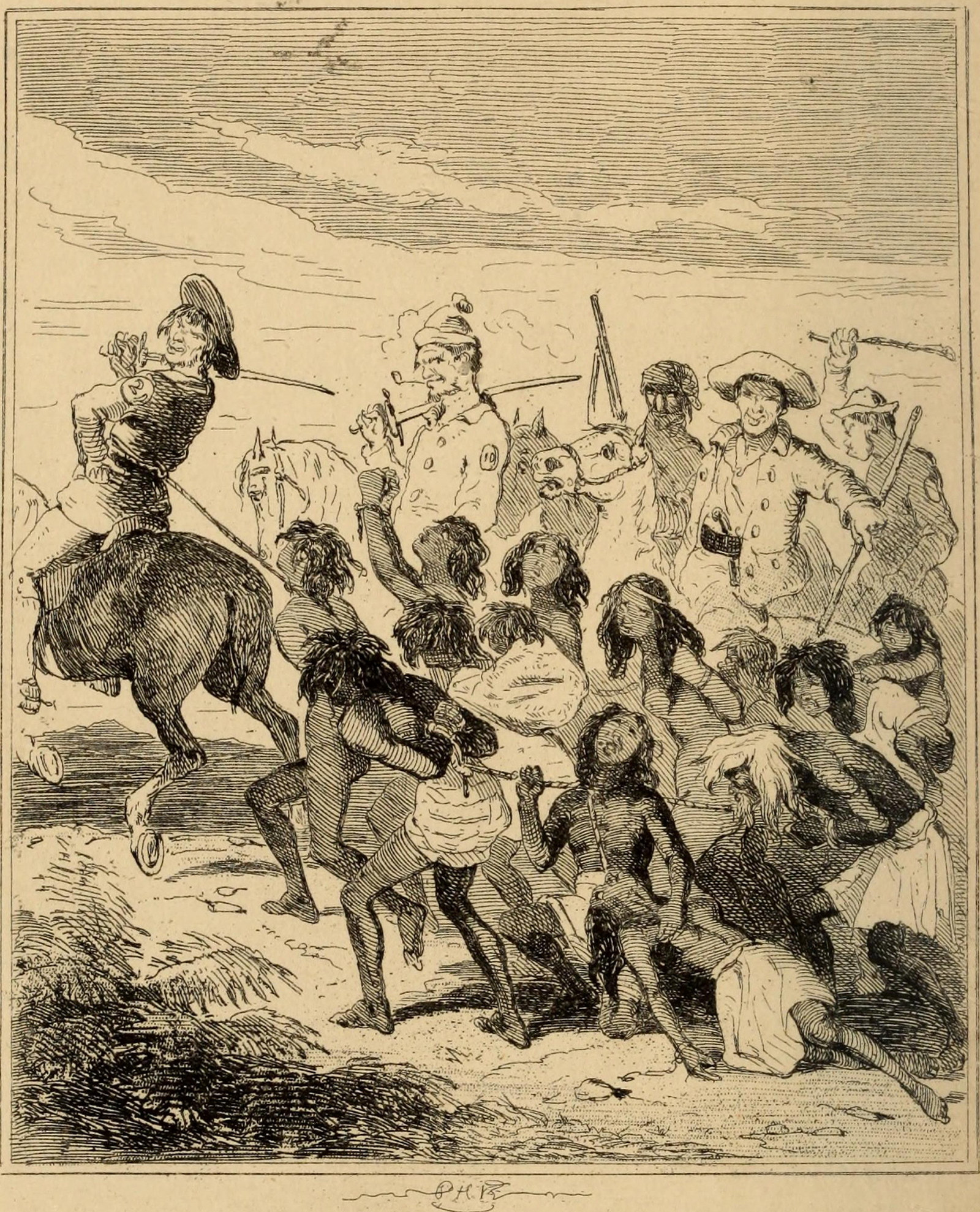

Within two years of being lauded as an expedition guide, Duall, whose name translates as ‘painfaced’ and apparently derived from his screwing up his face when smoking a bulbaloo (pipe), experienced one of several marked reversals of fortune.5 As hostilities escalated, Duall’s name appeared on a list of ‘hostile natives’ that Macquarie circulated to the ‘fittest and best troops’ from the colonial garrison whom in April 1816 he ordered out on another punitive expedition against Aboriginal people in the ‘disturbed districts’.6 As part of this extensive military operation, Lieutenant Parker and some soldiers went to the settler Woodhouse’s farm to retrieve ‘Duall and Quiet two hostile natives who had been taken on Mr Kennedy’s farm in the morning’.7 Hamilton Hume’s uncle John Kennedy was a known sympathiser towards Dharawal people. He offered them shelter during times of turmoil, and in turn his family’s farms had been protected by Dharawal from Aboriginal attacks.8 On 22 April 1816 Parker arrested the fugitives and Duall was taken to Liverpool Gaol. Quiet was kept on hand to show Parker the location of ‘that body of natives to which he belong’d’ before also being sent to Liverpool.9

Duall was in custody for three months before his fate was made public by Macquarie in the Sydney Gazette. The Governor described him as ‘dangerous to the peace and good order of the community’ and explained how Duall had been sentenced to death.10 However, Macquarie had remitted the sentence, replacing it with seven years’ banishment to Van Diemen’s Land.11 By the time Duall’s fate was printed in the newspaper, he was on the brig Kangaroo with one hundred other male convicts bound for Van Diemen’s Land. Macquarie instructed the Commandant at Port Dalrymple, Brevet-Major James Stewart, that the ‘Black Native’ Duall was ‘to be kept at Hard Labour and to be fed in the same manner as the other Convicts.’12

When Duall arrived in Van Diemen’s Land in 1816, the island colony was in a state of chaos. Many convicts were ‘totally without bedding’ and ‘a large portion of the prisoners have not had Jackets, etc., for three Years.’13 Convict absconders known as bushrangers or banditti plagued the land.14 Such men committed ‘very violent Excesses’, particularly in the area around Port Dalrymple where Duall had been sent, robbing houses and stealing stock to survive.15 Soldiers garrisoned at Port Dalrymple had descended into a ‘state of intoxication and insubordination’, setting fire to their barracks, burning their fences and those of their officers, destroying the gardens of the Commandant’s house, and robbing the Assistant Pilot and Acting Chief Constable before driving them away.16 After serving two years of his seven year sentence, Duall was recalled in late 1818 to Sydney by Macquarie where he arrived in late January 1819 on the Sindbad.17

Duall’s early recall from Van Diemen’s Land was precipitated by Charles Throsby’s request to utilise him as an interpreter on an exploratory journey. As Throsby appreciated, indigenous diplomacy was an essential prerequisite to successful attempts to explore the Australian continent. Throsby and his party, including Duall, set out from Airds on 25 April 1819 to find a direct route from the Cowpastures to Bathurst. They were accompanied by another interpreter, Bian, and guided by Coocoogong, a Gundungurra man. Throsby did not make extensive mention of any members of his expeditionary party, either black or white, in his journal. However, he was clearly concerned for their health and recorded in his journal after two days traveling ‘a Native Boy, who came with us being taken very ill, was obliged to stop … and made a hut for the night’.18 The journal entry does not reveal whether the afflicted person was Duall, Coocoogong, or Bian. By the next morning the patient had recovered sufficiently to travel up the Mittegong Range.

Following the expedition’s success, Throsby asked Macquarie to make Coocoogong ‘Chief of the Burrakburrak Tribe, of which place he is a Native’, as a means of ‘tranquilizing the Natives about Bathurst’, an area intended for more intensive colonial occupation.19 He asked that Duall and Bian be given ‘a Plate as a Reward of Merit’.20 Such titles and breastplates awarded to Aboriginal people in the early years of colonial contact functioned as symbols of colonial power and authority. Their bestowal formed part of a strategy British colonists used to try to break down traditional power structures and replace clan-selected chiefs with leaders sympathetic to the colonial administration. Throsby was given a land grant of 1,000 acres. The remaining white expeditioners received smaller land grants for their services.21

Duall enjoyed a distinguished career as an interpreter and guide to numerous exploratory expeditions.22 In 1826 he was named as one of seven ‘chiefs’ who participated in the Government’s ‘corroborie or annual festival’ for Aboriginal people at Parramatta. The leading men were ‘seated at the head of their respective tribes’ who ‘gave three loud cheers’ when they were served a dinner of ‘roast and boiled beef, soup, plum pudding, and grog’. About two hundred Aboriginal people attended the festivities along with well-known colonial personalities including Governor Ralph Darling, Reverend William Cowper, and Reverend Samuel Marsden.23 Duall was last mentioned in the colonial records in 1833 when he received a blanket in the annual distribution. At the time, he was aged around 40 and was living at the Cowpastures with his wife and child.24

Notes

1. James Kohen, The Darug and their Neighbours, Blacktown, Darug Link, 1993, 62-63.

2. Carol Liston, ‘The Dharawal and Gandangara in Colonial Campbelltown, New South Wales, 1788-1830’, Aboriginal History, Volume 12, 1988, 60.

3. Macquarie to Earl Bathurst, 18 March 1816, Historial Records of Australia (HRA), Series I, Volume IX, 52-3.

4. Liston, ‘The Dharawal and Gandangara in Colonial Campbelltown’, 50.

5. John McGuanne, ‘Centenary of Campbelltown: Appin’s Pride’, Lone Hand, 1920, cited in Robert Webster, Currency Lad: the Story of Hamilton Hume and the Explorers, Avalon Beach, Leisure Magazines, 1982, 19.

6. Lachlan Macquarie, ‘Instructions to Schaw, Wallis, and Dawe’, New South Wales Colonial Secretary’s Office Correspondence, Reel 6045, 149-50, TAHO; John Connor, The Australian Frontier Wars, 1788-1838, Sydney, University of New South Wales Press, 2002, 49-52.

7. Lieutenant A E Parker to Macquarie, ‘Report of a Detachment of the 46th Regt. from the 22nd April to the 5th May 1816’, Reel 6045, 60, TAHO.

8. Liston, ‘The Dharawal and Gandangara in Colonial Campbelltown’, 52-4.

9. Parker to Macquarie, ‘Report’, Reel 6045, 60-61, TAHO. Quayat is a spelling variant for Quiet.

10. Parker to Macquarie, ‘Report’, Reel 6045, 60-61, TAHO. Quayat is a spelling variant for Quiet.

11. Sydney Gazette, 3 August 1816, 1.

12. Macquarie to Brevet-Major James Stewart, 31 July 1816, HRA, Series III, Volume II, 471.

13. Lieutenant-Governor William Sorell to Macquarie, 8 December 1817, HRA, Series III, Volume II, 289.

14. Macquarie to Earl Bathurst, 7 May 1814, HRA, Series I, Volume III, 250.

15. Macquarie to Earl Bathurst, 7 May 1814, HRA, Series I, Volume III, 250.

16. Sorell to Macquarie, HRA, Series III, Vol II, 340-41; Macquarie to Sorell, HRA, Series III, Vol II, 354.

17. New South Wales Colonial Secretary’s Office Correspondence, Reel 6006, 188-89, TAHO; ‘Transfer of Dicall [Duall] from Port Dalrymple to Sydney’, New South Wales Colonial Secretary’s Office Correspondence, Reel 6006, 188, TAHO. ‘Arrival in Sydney from Port Dalrymple per “Sindbad”’, New South Wales Colonial Secretary’s Office Correspondence, Reel 6006, 296, TAHO.

18. Charles Throsby, ‘Journal of a Tour to Bathurst Through The Cow Pastures Commencing on April 25th 1819’, New South Wales’ Colonial Secretary’s Office Correspondence, Reel 6038, 78, TAHO.

19. Charles Throsby, ‘Journal of a Tour to Bathurst Through The Cow Pastures Commencing on April 25th 1819’, New South Wales’ Colonial Secretary’s Office Correspondence, Reel 6038, 89, TAHO.

20. ibid. Breastplates were based on military gorgets. Often crescent shaped, they were inscribed metal plaques that hung from chains and were worn around the recipient’s neck.

21. Macquarie, ‘Government and General Orders’, 31 May 1819, 48-49.

22. Webster, Currency Lad, 19.

23. ‘The Corroborie at Parramatta’, Australian, 19 January 1826, 3.

24. ‘Return of the Cowpasture Aborigines for 1833’, State Archives and Records New South Wales (SARNSW) 4/6666.3, cited in Liston. ‘The Dharawal and Gandangara in Colonial Campbelltown’, 1988, 58-9.

Published on

First Nations stories from Convict Sydney

Browse all

Convict Sydney

Myall Creek massacre

On Sunday 10 June 1838, at least 28 Aboriginal people were massacred by a group of 12 Europeans at Myall Creek Station

Convict Sydney

William Dawes

Officer of marines, scientist, astronomer, engineer, surveyor, teacher and administrator

Convict Sydney

Tom and Fowler

On 4 May 1843, Fowler and fifteen other Aboriginal men broke into watchman Patrick Carroll’s hut near the McLeay River, 107 miles from Port Macquarie

Convict Sydney

Murphy

‘Murphy’ was one of a few Aboriginal men who tragically found themselves trapped in the British convict system