Convict hulks

In the 21st century we are accustomed to thinking of imprisonment as one of the more obvious forms of punishment for convicted criminals. This was not so in the past.

The industrial revolution, social change and war caused great changes in the lives of British people in the 17th and 18th centuries. Extreme poverty was a fact of life for many, and desperate people resorted to crimes such as theft, robbery and forgery in order to survive. If caught and convicted, they faced a harsh and complicated criminal code. Imprisonment was only one of a range of sentences that judges could inflict and, with no national prison system and few purpose-built prisons, it was often not their first choice. Instead, most criminal offences were punishable by death, public humiliation in the form of branding, whipping, hair cutting, the stocks or the pillory, the imposition of a fine, or transportation overseas.

British authorities had used the transportation of criminals overseas as a form of punishment since the early 17th century, particularly to provide labour in the American colonies. When in the 18th century, the death penalty came to be regarded as too severe a punishment for offences such as theft and larceny, transportation to North America became an even more popular form of sentence.

The American War of Independence (1775–1783) put an end to this human export. Convicts sentenced to transportation were sent instead to hulks, old or unseaworthy ships, generally ex-naval vessels, moored in rivers and harbours close enough to land for the inmates to be taken ashore to work. Although originally introduced as a temporary measure the hulks quickly became a cost-efficient, essential and integral part of the British prison system.

Once tried and sentenced convicts were sent to a receiving hulk for four to six days, where they were washed, inspected and issued with clothing, blankets, mess mugs and plates. They were then sent to a convict hulk, assigned to a mess and allocated to a work gang. They spent 10 to 12 hours a day working on river cleaning projects, stone collecting, timber cutting, embankment and dockyard work while they waited for a convict transport to become available. In some cases convicts sentenced to transportation spent their entire sentence (up to seven years) on board the hulks and were never sent overseas.

From 1776 to 1802 all English hulks were operated by private individuals such as the shipowners Duncan Campbell and James Bradley, under contract to the British government. These included the Justitia, Censor, Ceres and Stanislaus on the River Thames at Woolwich, the Chatham and Dunkirk at Plymouth, the Lion at Gosport and La Fortunee at Langstone Harbour near Portsmouth.

In 1784, the British government passed legislation authorising the transportation overseas of convicts from the hulks. The notion of using hulks as floating prisons was exported along with the convicts. Eventually convict hulks were established at many British colonies including Gibraltar, Bermuda, New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania).

From 1802 the private contractors in England came under the direct supervision of Aaron Graham, the first government-appointed Inspector of Hulks. All overseas hulks were operated by the British or colonial governments, including those in Bermuda (from 1799), Malta (1800), Nova Scotia (1813), Barbados (1814), Ireland (1817), Van Diemen’s Land (1824), New South Wales (1825), Gibraltar (1842) and Victoria (1852).

With Graham’s retirement in 1814 John Capper was appointed Superintendent of Prisons and the Hulk Establishment. The private contractors were phased out and replaced by government-operated hulks. Initially Capper responded to his onerous responsibility with great enthusiasm. He commenced an improvement program that involved refitting the hulks to allow for the easier separation of convicts, and made regular inspections and reports to parliament on the conditions of the hulks. He also introduced a six-tiered convict classification system that included the possibility of government pardons for good behaviour, and literally separated the men from the boys by commissioning a hulk, the Bellerophon, for boys under the age of 18.

A Bermudan Connection

Of all British convict establishments, the one in Bermuda was arguably the most brutal.1 From 1824 to 1863 it was home to thousands of male convicts sentenced by British and Irish courts to transportation with hard labour for terms of up to 14 years. Of the 9000 convicts sent to Bermuda close to 2000 died.

Established by a British Government Order in Council in 1824 the Bermuda Convict Establishment was the responsibility of the Home Office until the late 1840s when it was transferred to the Colonial Office. Unlike other colonies established using convict labour, such as New South Wales or Van Diemen’s Land, the vast majority of convicts sentenced to Bermuda were not allowed to settle in Bermuda but were either returned to Britain or sent on to another colony such as Western Australia at the end of their sentence.

The primary purpose of the Bermuda establishment was strategic in that it provided essential and valuable labour to the Royal Engineers constructing the Royal Naval Dockyards and fortifications. Under the direction of these engineers and the guards, the convicts were employed as carpenters, quarrymen, stone cutters and carters, lime washers and labourers as well as sail makers, engine men, teachers, shoemakers, stewards, bookbinders, gas men, tailors, nurses, cooks, servants, washermen, pump operators, scavengers, gardeners, barbers, mat makers, rope makers, oakum pickers and painters.

In 1826 the British Government sent the Dromedary, an ex-naval store ship, to Bermuda to provide accommodation for convicts working on the dockyards and fortifications. The Dromedary had an Australian connection: as a convict transport it had undertaken several voyages to the Australian colonies, including ferrying Governor Lachlan Macquarie and the 73rd Regiment to New South Wales in 1809. Once in Bermuda, the Dromedary remained moored for nearly 40 years in the same part of the harbour, serving as hulk, store ship and kitchen for the thousands of male convicts and their guards.

In 1982 Chris Addams and Mike Davis obtained permission from the Bermudan Government to excavate the Dromedary hulk’s anchorage area. One of the major aims of the archaeological project was to augment historical research and find out what conditions were really like on the Bermudan convict hulks. Working in appalling conditions in almost zero visibility the divers used a suction dredge to peel away metres of sand, shell, coal and limestone deposits to uncover what is arguably the largest collection of 19th century convict material directly associated with convict life on the hulks.

Thousands of artefacts were recovered during the course of the excavations, including whale oil lamps, pewter mugs, engraved spoons, clay pipes, bottles, buttons, seals, coins, trinkets, charms, rings, beads, gaming pieces, religious items, knife handles and gaming boards. Careful plotting of the artefacts not only revealed what items were associated with the guard and what items were related to the convicts but also uncovered evidence of a large-scale shipboard economy based on the production of mementoes, curios and specimens. Beautifully made objects carved out of bone, shell, metal and stone were sold by their convict makers to the guards, visiting sailors and free settlers for tobacco, alcohol, food and money.

Over 500 artefacts of Bermudan convict hulk material has been brought to Australia for the first time, exclusively for this exhibition. Australia’s own history of convict hulks is the other focus of the exhibition.

Hulks in Australia

Although the Australian colonies were established as penal settlements with the prisoners assigned within the community, the need for more secure accommodation quickly became apparent, especially for refractory or rebellious offenders and those found guilty of an offence in the colony, called secondary offenders. Following the British example, colonial authorities in New South Wales, Van Diemen’s Land and Victoria purchased old or unseaworthy ships and converted them into floating prisons.

The hulks in Australia had two main uses. They provided prison accommodation when existing colonial gaols were unsuitable or already full, and they served as floating holding pens for prisoners convicted of secondary offences while they awaited ships to transfer them to dreaded places like Norfolk Island or Port Arthur in Van Diemen’s Land.

The Phoenix was the first floating prison used in Australian mainland waters.2 Between 1825 and 1837, it was moored in Sydney Harbour at Lavender Bay, known then as Hulk or Phoenix Bay, as a sobering symbol of the ‘strength and terror’ of the colony’s police, according to Governor Brisbane. It housed up to 260 prisoners at a time, including those awaiting trial, convict witnesses giving evidence, invalid convicts waiting for a ship to Port Macquarie Invalid Station, and those under colonial sentence of re-transportation. As with other prison hulks around the world, the human cargo on board was a source of cheap labour. Phoenix convicts worked from dawn to dusk predominately in ‘shore parties’ quarrying stone, cutting timber, building fortifications, reclaiming land and working in dockyards.

The Anson hulk on the Derwent River in Hobart was unusual in that it housed only female convicts. It was used to alleviate overcrowding at Hobart’s Cascades Female Factory and to stop newly arrived convict women mixing with ‘old hands’ there by having them spend six months probation on the Anson. At the end of their probation the women were sent to hiring depots to be assigned to settlers as domestic servants, or, occasionally, were hired directly from the hulk. Over 4000 women spent time on the Anson between 1844 and 1850, when the last inmates were moved to Cascades. The women worked at spinning, sewing, dressmaking and laundering. They made straw bonnets, knitted stockings from the wool processed on board, made shoes, picked oakum and prepared food.

The hulks established in the Victorian colony were an indirect result of the discovery of gold in 1851. Victoria’s population grew rapidly and the prison system was soon over-stretched. The newly constituted government established floating prisons on the President, Success, Deborah and Sacramento in Hobson’s Bay at Williamstown. By the end of 1853, 455 prisoners were held on these hulks. A fifth hulk, the Lysander, was added in 1854. Conditions were the most severe on the President, where shackled inmates were confined without work in cramped conditions under orders of silence. The next level was the Success, from where prisoners were sent ashore in chain gangs to work cutting or quarrying stone. Insubordination could mean transfer to the President. If well behaved, prisoners could be moved to other hulks and eventually to one of the stockades before ultimately obtaining their freedom. In 1857, a group of Success prisoners was hanged for the murder of John Price, Inspector General of Penal Establishments in Victoria. Price had a reputation for inhumane treatment of prisoners and his assassination triggered an inquiry into the use of the hulk system, leading to its ultimate demise.

The Floating Museum

In 1890 the Success was bought by entrepreneurs and fitted out as a floating museum. It featured life-like wax figures wearing prison clothes and manacles, and sensationalised stories of the convicts who had filled its cells when it was a prison hulk. Thousands of tourists visited the Success in Sydney but in June 1892, it took on water and sank. The submerged ship was sold and re-floated and re-opened for tourists at Circular Quay, touring afterwards to Newcastle, Brisbane, Hobart and Port Adelaide.

In 1895, the Success sailed to England and toured British coastal cities until 1912 when American interests bought it. It then successfully toured both the east and west coasts of the United States for many years. In 1925, the Australian Commissioner in New York actively sought to have the floating museum closed, arguing it was ‘an exhibit to be condemned as the worst advertisement for Australia in any part of the world’. Australian government lobbying continued well into the 1930s without effect. In 1946, after near continual exhibition for over 50 years, the Success was burnt and sunk in Lake Erie, near Detroit.

The value of the work carried out by the convicts on board the hulks both in England and the overseas colonies was immense.3 However, following several parliamentary inquiries, John Capper retired in 1847 and the British government set about reforming the system. More land prisons were built and the hulks were slowly decommissioned. They were similarly closed down in Britain’s colonies, with the last hulk being decommissioned in Gibraltar in 1884.

Between 1776 and 1884 the British government had converted more than 150 ships into convict, guard, receiving, hospital and school hulks. Over time these hulks and the thousands of male and female convicts they housed played an essential and integral function in British military and colonial expansion.

Kieran Hosty / Bridget Berry Curators

Notes

- Medical Officer returns for 1826 to 1856 indicate that the Bermuda Convict Establishment had a much higher rate of sickness and death than English prisons and hulks due to cholera, typhus, yellow fever, dysentery, and construction and quarrying accidents.

- Supply had been converted into a hulk in Sydney before 1824 but was not used as a floating prison but rather for the storage of provisions and as a receiving depot for newly arrived prisoners. Another prison hulk, the Duke of York, housed convicts in Hobart from as early as 1824.

- In 1852 it was estimated that each of the convicts generated more than £17 a year towards the cost of their confinement compared to less than £5 for prisoners at Pentonville and £3 for those at Parkhurst.

Convict Sydney

Convict Sydney

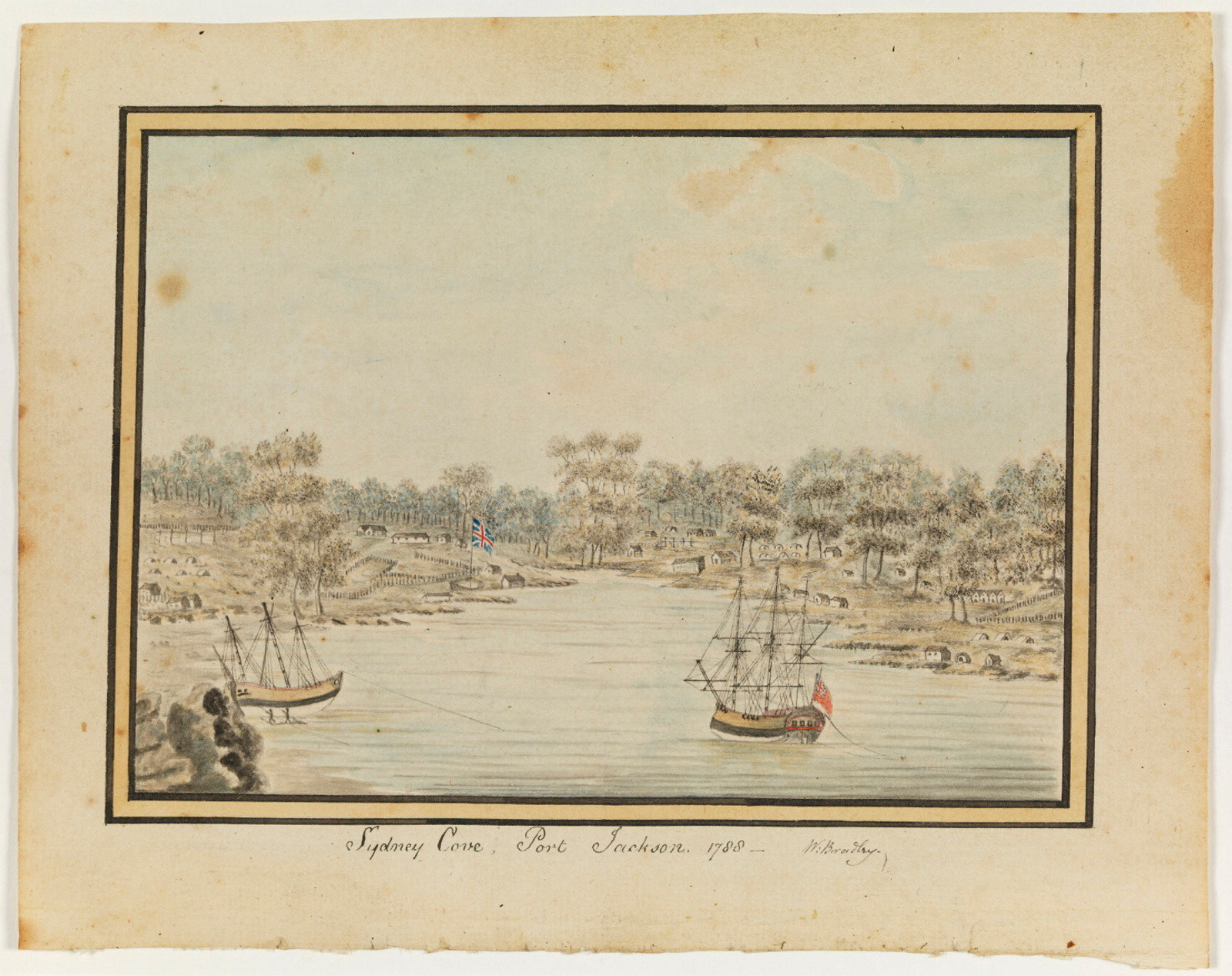

From a struggling convict encampment to a thriving Pacific seaport, a city takes shape

First Fleet Ships

First Fleet Ships

At the time of the First Fleet’s voyage there were some 12,000 British commercial and naval ships plying the world’s oceans

Published on

Day in the life of a convict

Convict Sydney

1801 - Day in the life of a convict

In the young colony, there was no prisoner’s barrack - the bush and sea were the walls of the convicts’ prison

Convict Sydney

1820 - Day in the life of a convict

By 1820 the days of relative freedom for convicts in Sydney were over

Convict Sydney

1826 - Day in the life of a convict

The hot Sydney summer of 1826 ended with almost 1,000 convicts living at the overcrowded Barracks

Convict Sydney

1836 - Day in the life of a convict

By 1836, two-thirds of the convicts in the colony were out working for private masters, and government convicts made up only a small group

Convict Sydney

1844 - Day in the life of a convict

Fraying at the edges, these were the Barracks’ darkest days with only the worst convicts remaining

Related

Why were convicts transported to Australia?

Until 1782, English convicts were transported to America, however that all changed after 1783

Who were the Hyde Park Barracks convicts?

Pick-pockets and pirates, confidence tricksters and conspirators, rebels and rascals – between 1819 and 1848, Hyde Park Barracks had them all

First Fleet Ships

Voyage

The First Fleet voyage took between 250 and 252 days to complete, with 68 of these days spent anchored in ports en route

Hyde Park Barracks – the convict years

In 1788, the penal colony of New South Wales was established on the Country of the Gadigal people