Grief in the archives: a Blak reflection on Sorry Day

In this article, Dylan Hoskins, Project Assistant on the First Nations Community Access to Archives project, reflects on the significance of National Sorry Day through his lived experience as an Aboriginal person. The article critically examines the systemic removal of Aboriginal children through legislation such as the Aborigines Protection Act 1909 (NSW) and its 1943 amendment and engages with the findings of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families, outlined in the Bringing them home report, published in 1997. Drawing on the NSW State Archives Collection and his personal narrative, Dylan explores how colonial bureaucracy inflicted intergenerational trauma, and calls for genuine, reparative change beyond symbolic gestures.

Content sensitivity statement

Please be advised this article contains language and images that depict frontier violence and removal of children.

Sorry Day is not a footnote in Australian history. It is an open wound of this nation. For many of us Aboriginal people, it is not just remembrance, it is survival. It is waking up with stories half told and half known. It is reclaiming the echoes of stolen lullabies. This piece is a personal and political reckoning with the institutional systems that removed Aboriginal children from their families, and the silence that still surrounds them.

The Aborigines Protection Act 1909 marked a pivotal moment in the legal codification of Aboriginal child removal. Under the guise of ‘protection’, the Act enabled the NSW Board for the Protection of Aborigines to take sweeping control over the lives of Aboriginal people, particularly children. Section 7(c) gave the Board the authority to ‘provide for the custody, maintenance, and education of the children of aborigines’, a clause that became the foundation for decades of child removals without consent.

The 1943 amendment to the Act restructured this system, renaming the Board the Aborigines Welfare Board and granting it new corporate powers, including the right to buy and sell land, issue exemption certificates, and determine who was subject to the Act (Aborigines Protection (Amendment) Act 1943, sections 3A, 3B and 4B). These certificates of exemption stripped people of their Aboriginal identity while overtly fracturing communities through bureaucratic erasure.

The State Archives Collection holds the earliest records that document the forced removal of Aboriginal children and the beginnings of a calculated system of family separation. These records, though framed in administrative language, reveal a disturbing moral detachment from the lives they upended. They are not neutral documents; they are colonial artefacts of violence. As an Aboriginal person, reading these materials feels like reviewing a cold case murder: silent, filed, categorised, but not forgotten.

The 1997 Bringing them home report offered the most comprehensive public acknowledgement of the Stolen Generations. It catalogued personal testimonies of trauma, loss and institutional abuse. It also exposed the widespread use of duress, deceit and force in removing children.1

One submission to the inquiry recounts how mothers were physically removed from police vehicles while their screaming children were taken away: ‘They pushed the mothers away and drove off, while our mothers were chasing the car’.2 These were not isolated incidents; they were the result of coordinated state policy.

As an Aboriginal person, I exist in a world that tried, and still tries, to erase me. The Aboriginal child welfare system and, later, the education and adoption systems, operated on nuclear family ideals. Kinship, cultural knowledge and identity had no place in their records. But we existed. We still do.

My identity is a form of resistance. Our Aboriginality has always persisted – before the words, before the laws, before forced governance. The state may not have recorded our actuality, but the land remembers.

Saying ‘sorry’ is not enough. Of the 54 recommendations made in Bringing them home, including reparations, culturally safe healing services and improved access to personal records, many remain unimplemented.

True reparation means more than an apology. To me, it means returning land, funding Indigenous-led services, embedding truth-telling in the national curriculum, and recognising the sovereignty of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in legal and cultural frameworks.

The Aborigines Protection Act, its amendments, and the silence that followed have cast long shadows over generations. For Aboriginal people, the past is not past. It is encoded in our trauma, our relationships, our love and our art. Sorry Day should not be a moment. It should be a movement.

Notes

1. Bringing them home: report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families, Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC), Sydney, 1997, pp61–70

2. ibid, p6

Published on

Read more

Browse all![NRS 12061 [12/8749.1] 62/1515pt1, p334](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/zl9du87e/production/f95209714e7233f28b7abc814dbc999c0d9033e3-1404x2000.jpg?rect=0,525,1404,861&fit=max&auto=format)

First Nations

Advocacy, allyship and the rise and fall of the Aborigines Protection Board

In the lead-up to 26 January, the State Archives Collection provides opportunities to explore and reflect on past examples of advocacy and allyship in the fight for First Nations rights

![[Sydney from the north shore], Joseph Lycett, 1827.](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/zl9du87e/production/efb0ca986f6e159dd142f8014c35c3b1010cbc06-1346x908.jpg?fit=max&auto=format)

Hearing the music of early New South Wales

A new website documents an exciting partnership between Museums of History NSW and the University of Sydney in an exploration of Indigenous song and European settler vocal and instrumental music in early colonial NSW

First Nations

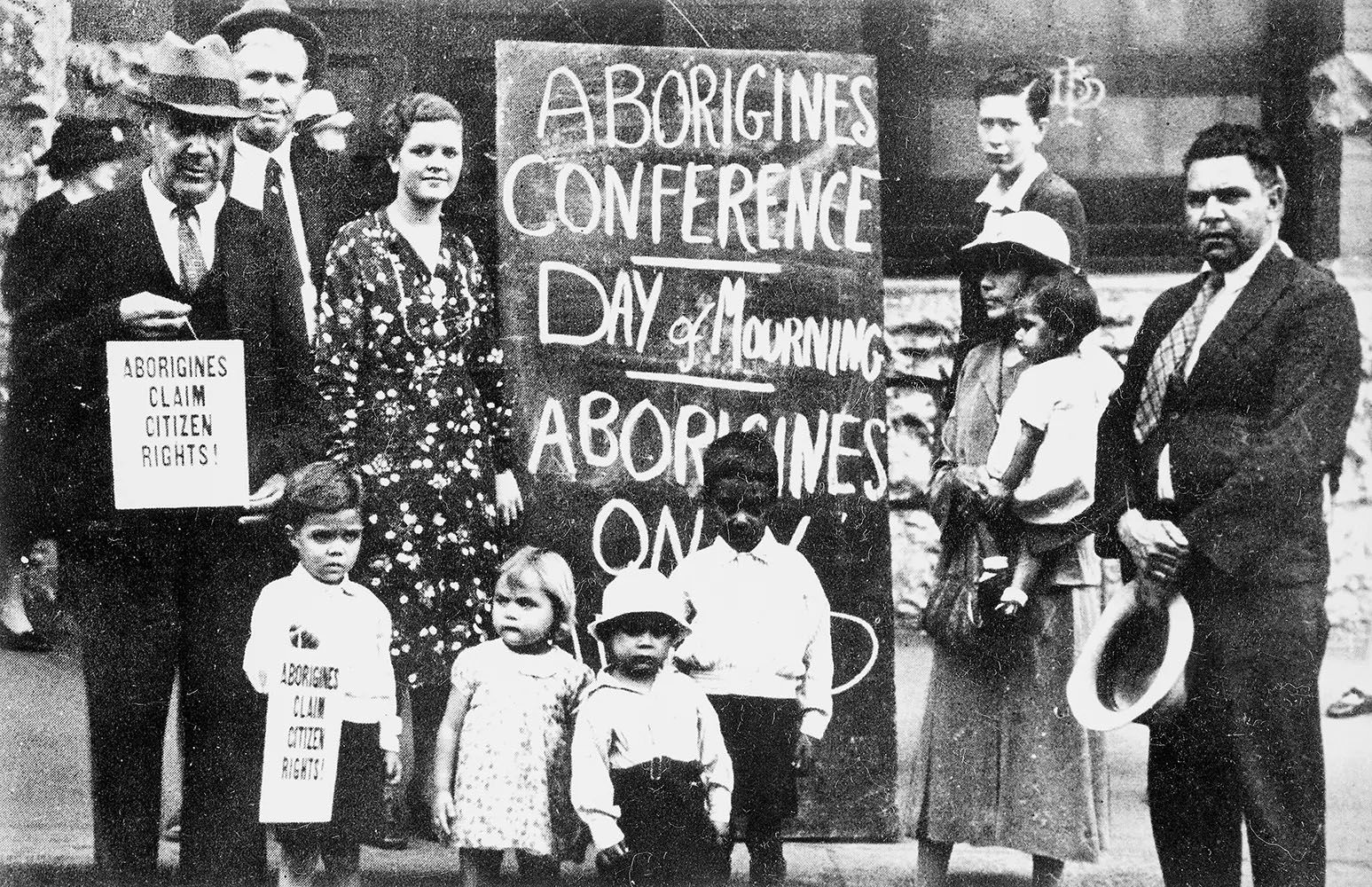

Day of Mourning

January 26 has long been a day of debate and civic action. Those who celebrate may be surprised of the date’s significance in NSW as a protest to the celebrations of the anniversary of the arrival of the First Fleet on what was then “Anniversary Day” in NSW