What was life in early Sydney like for convicts?

By 1801 Sydney had grown into a little village with streets and buildings. Many of the buildings were made of timber and stone, some older houses were made from .

Convicts lived in their own homes in an area known as ‘The Rocks’, some with their families. But it wasn’t just convicts living in the village; local Aboriginal people lived there too. They camped near the convict houses, fished on the harbour, traded goods and food with townsfolk and brought news from further away.

Aboriginal people had lived in and around Sydney Cove for thousands of years and they called it . By now they were used to the sight of new ships arriving and they would often be out on the harbour in their canoes.

For newly arrived convicts, the environment of Sydney was strange and very different to what they were used to. During summer, days of unbearable heat were often followed by ferocious thunderstorms and torrential rain.

Overhead flew flocks of brightly coloured parrots and cockatoos, while kangaroos, echidnas, wombats and goannas roamed the scrubby bush. Most convicts enjoyed living in Sydney more than living on settler farms in the bush. In town they could visit friends or family for a cup of tea or lunch, enjoy a dance in fancy clothes or visit a theatre. When they were not working, they gambled with their money, played games and relaxed.

The Tank Stream

A natural freshwater stream ran through the town, and flowed into the harbour.

This water source is why Governor Phillip chose to settle at Sydney Cove, instead of Botany Bay. Long before the arrival of Europeans, the local Gadi people also used this stream as a source of fresh water. The stream gave the early colonists drinking water. It also divided the early settlement in two. Government buildings were to the east of the stream and convicts lived on the western side.

In the 1790s three or four tanks were dug into the stream's bedrock to store water. Each tank held about 20,000 litres when full.

The stream then became known as the Tank Stream.

To keep the water clean, Phillip had fences built along the stream's banks. Washing clothes in the stream was not allowed and animals were not meant to graze close by. But as the colony grew, the once natural source of fresh water became more polluted. By the 1820s it had become an open sewer.

How did the colony of NSW develop?

Terra nullius, Perspectives, Reconciliation

What was terra nullius? How can you examine Australian history from Aboriginal perspectives? How does understanding past decisions, help Reconciliation?

What food did convicts eat?

Most convicts were given a daily ration by the government. They collected it from the government food store and were given:

- 450 grams of

- 450 grams of corn (sometimes still on the cob)

- 450 grams of wheat flour to make bread.

Women and teenagers were given smaller rations than the men – so they would have often been hungry.

Sometimes the meat was rotten because it had been kept for months, or even years, on a ship before being issued. In the colony, when the weather was bad and crops got damaged, the convicts were given less to eat.

If a convict had some money they could buy more food. Better still, if they had a small vegetable garden at their home they could eat, or sell, what they were able to grow. Some convicts tried to catch fish or collect oysters and shellfish in Sydney harbour to give them more to eat. They also tried to hunt animals like ducks, birds and kangaroos – but that was not easy.

Aboriginal people hunted, gathered and carefully managed the various local food sources, making sure they didn’t take too much. But when convicts started to hunt and collect food in the same areas, they often took too much. This put pressure on the environment and reduced the amount of food available.

What work did convicts do?

Convict men started work at 7am and did lots of different jobs. Most men worked for government ‘gangs’ although some worked for free settlers and soldiers. They cut down trees, sawed timber, made bricks, built doors, windows and furniture. Some men pulled carts and others moved buckets and barrels of water.

The government lumberyard (located on the corner of Bridge and George streets) was an important place where men with trades worked side by side.

Carpenters worked with wood, wheelwrights built wheels, tailors and shoemakers made clothes, and blacksmiths made chains and work tools. A few educated convicts that could read and write, like James Hardy Vaux, were given government desk jobs.

Female convicts did different work to the men. Many of them worked for families as cooks, maids, nurses or washerwomen. However, one female convict called Ann Marsh, ran a pub in the Rocks as well as a river ferry service between Sydney and Parramatta.

A lot of the work that convicts did affected Aboriginal people, their way of life and their close connection to their country. Cutting down trees and clearing land destroyed traditional hunting grounds. Catching fish and collecting oysters from the waterways meant there was less available for Aboriginal people to feed their families. Building farms and fences made it harder for Aboriginal people to travel across, care for and camp in areas that they had used and nurtured for many years.

What was it like inside a convict’s house?

Convicts were often quite comfortable. They lived in two or three roomed houses, shared with fellow convicts or with a family. They had tables and chairs, cooked dinner (like pea and ham soup) over a fireplace and ate their food on china crockery using silver cutlery!

They slept on beds with mattresses, washed their clothes with buckets and washboards, and hung it out on the line to dry in the sun. Some convicts kept animals like chickens and pigs and might also have tended a small vegetable garden.

Sydney as a little village.

The painting above (from 1803) shows visiting ships anchored in the harbour, houses with chimneys and fences and a simple system of streets. The long white building is the hospital and there are a range of different people in the foreground. The weather looks like a bright clear day.

Title: Sydney from the west side of the cove

Artist: George Evans

Date: 1802

Were the convicts well-behaved?

Most convicts worked hard and tried to behave well so that they would earn a ticket-of-leave. A ticket-of-leave meant a convict could work for himself or herself, earning money and enjoying more freedom.

William Noah is a good example of a convict who worked hard and was well-behaved.

Noah had been convicted of robbery in England and sentenced to transportation for life. He arrived in Sydney in 1799 and was sent to work at the government lumberyard, where he worked hard for many years. In 1818 he was given an Absolute Pardon, which meant his 'life sentance' was over, and he then lived in Sydney for the rest of his life as a free man.

However, if a convict was badly behaved, refused to work, stole food or tools, or tried to escape they could be punished with a flogging or a stint in chains. If their behavior was really serious they faced being sent to work in the mines of Newcastle or further away on lonely Norfolk Island.

What clothes did a convict wear?

Convict men were given work clothes, called ‘slops’, by the government. They got a cotton shirt, a blue woollen jacket and waistcoat, white trousers and shoes. They were also given a woollen cap or hat.

Women wore jackats, shifts (with a petticoat underneath), stockings, shoes and a cap on their head.

After work and on weekends male and female convicts would take off their government clothes and change into something nicer. They would wear fancy coats, tailor-made dresses, new shoes and hats, and buy new clothes with any money they had saved.

Activities

History skills in action (source analysis)

Artworks are a terrific way to learn about history. They often contain evidence (clues) that shows you what life was like in the past for different people and how places have changed over time.

Investigate both artworks for clues that help you answer the questions below. Then use those answers (as well as all the information provided above) to help you complete the creative writing task below.

Start with the first painting. Then investigate the sketch, it has a helpful key at the bottom with a lot of information about the different buildings and places you can see.

Click on the images to make them larger.

- Describe all the different people you can see in the painting and what they are doing.

- Look carefully – can you find any evidence of vegetable gardens in the front yards of the houses?

- Try and locate the Governor’s house – it faces the ship in the harbour, has two chimneys and is high up on a hill.

- What can you see being built on the shores of Sydney Harbour?

Now use the sketch to find out more about what the different buildings are, and who used them. Use the numbers in the key to start investigating.

Imagine you are a convict living near Sydney Cove around 1800.

Write a letter to a family member who lives back in London and tell them about:

- where you live, what you eat and the work you do

- the different people who live in Sydney, and where they live

- what the different buildings are like

- what the environment is like

- the different activities you see people doing each day around the town

- how you feel about living in Sydney.

Convict Sydney

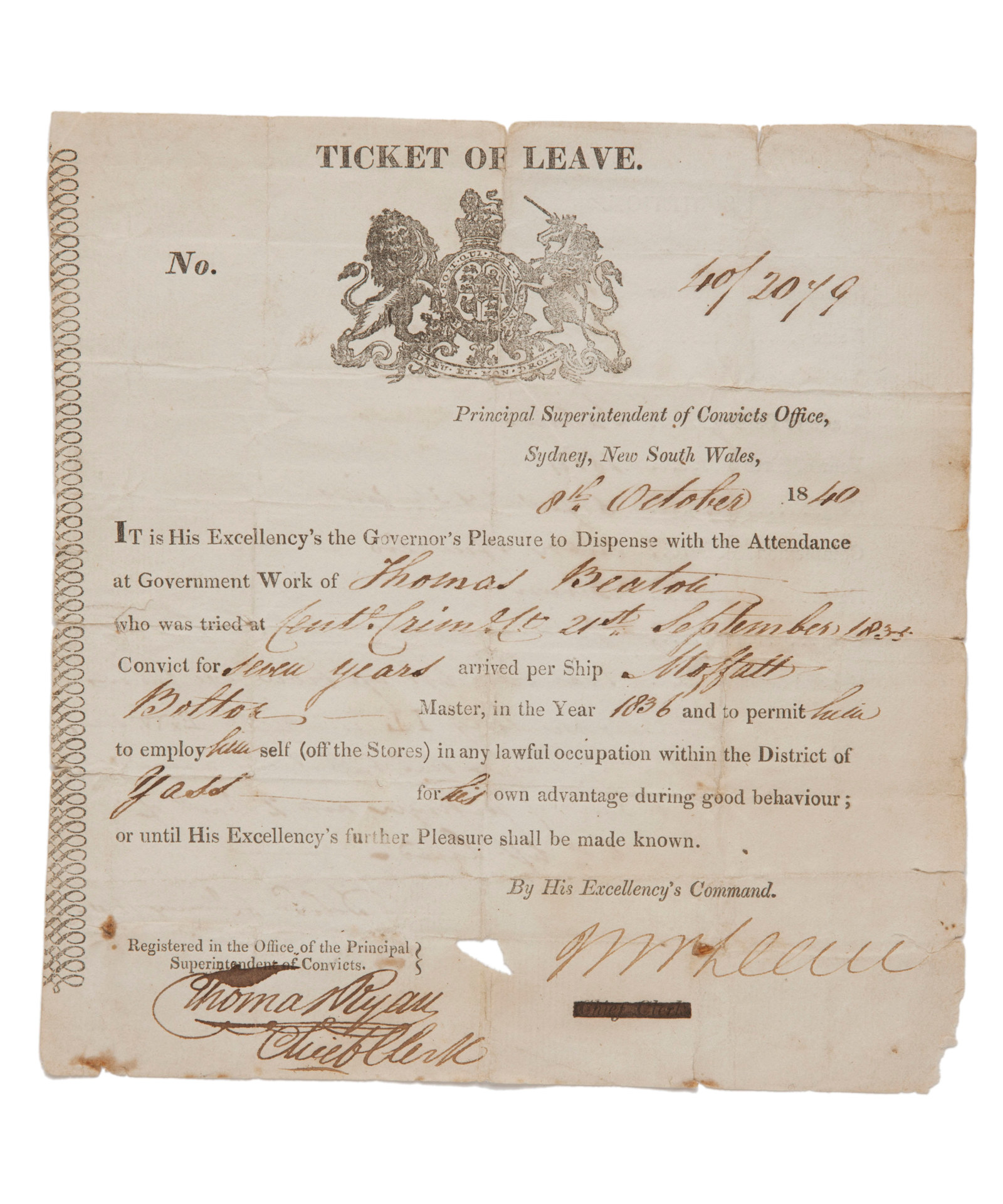

Ticket of leave

This Ticket of Leave granted to convict Thomas Beaton shows how well-behaved convicts could reduce the length of their sentences

Convict Sydney

Hack barrow

Convict brickmakers working at the Brickfields (now Haymarket) used hack barrows like this one, stacking 20 or 30 wet bricks on the timber palings along the top, for transporting them from the moulding table to the ‘hack’ yard for drying

Related

Convict Sydney

Convict Sydney

From a struggling convict encampment to a thriving Pacific seaport, a city takes shape

Learning resources

Explore our range of online resources designed by teachers to support student learning in the classroom or at home

Convict Sydney

Objects

These convict-era objects and archaeological artefacts found at the Hyde Park Barracks and The Mint (Rum Hospital) are among the rarest and most personal artefacts to have survived from Australia’s early convict period