How were convicts rewarded for good behaviour?

While some convicts broke the rules and were punished, most of them worked hard and tried to stay out of trouble.

Good behaviour could earn a convict different types of rewards or privileges. They might have been given extra food or more free time, or been given a job with more responsibility – such as being a constable (a convict assigned to supervise the behaviour of the other convicts) at the Barracks.

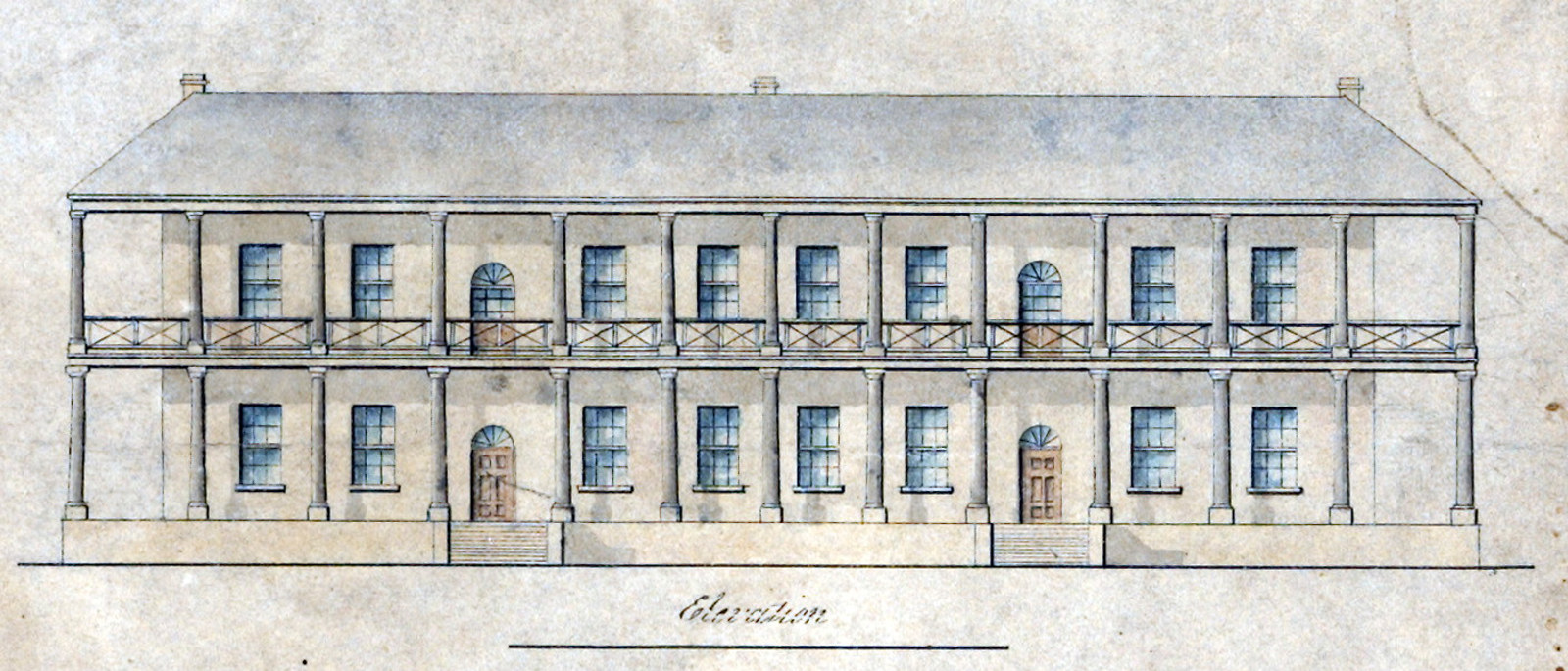

Francis Greenway

In 1812 Francis Greenway was sentenced to death for the crime of forgery. However, his sentence was then changed to transportation to NSW for 14 years. He arrived in Sydney in February 1814, and his wife and three children arrived a few months later.

As a trained architect, Greenway was a valuable person to the new colony. He was given a ticket of leave in 1815 and was employed by the government, designing many of their new buildings – including the Hyde Park Barracks.

In December 1817, Governor Macquarie rewarded him for his good behaviour and hard work with a conditional pardon. Then, in May 1819, the governor rewarded him with an absolute pardon.

Greenway also designed St James’ Church (opposite the Hyde Park Barracks), where the convicts had to attend service every Sunday. Built in 1824, the building still stands today.

Official rewards

A well-behaved convict could be rewarded in different ways. Some of the official rewards were:

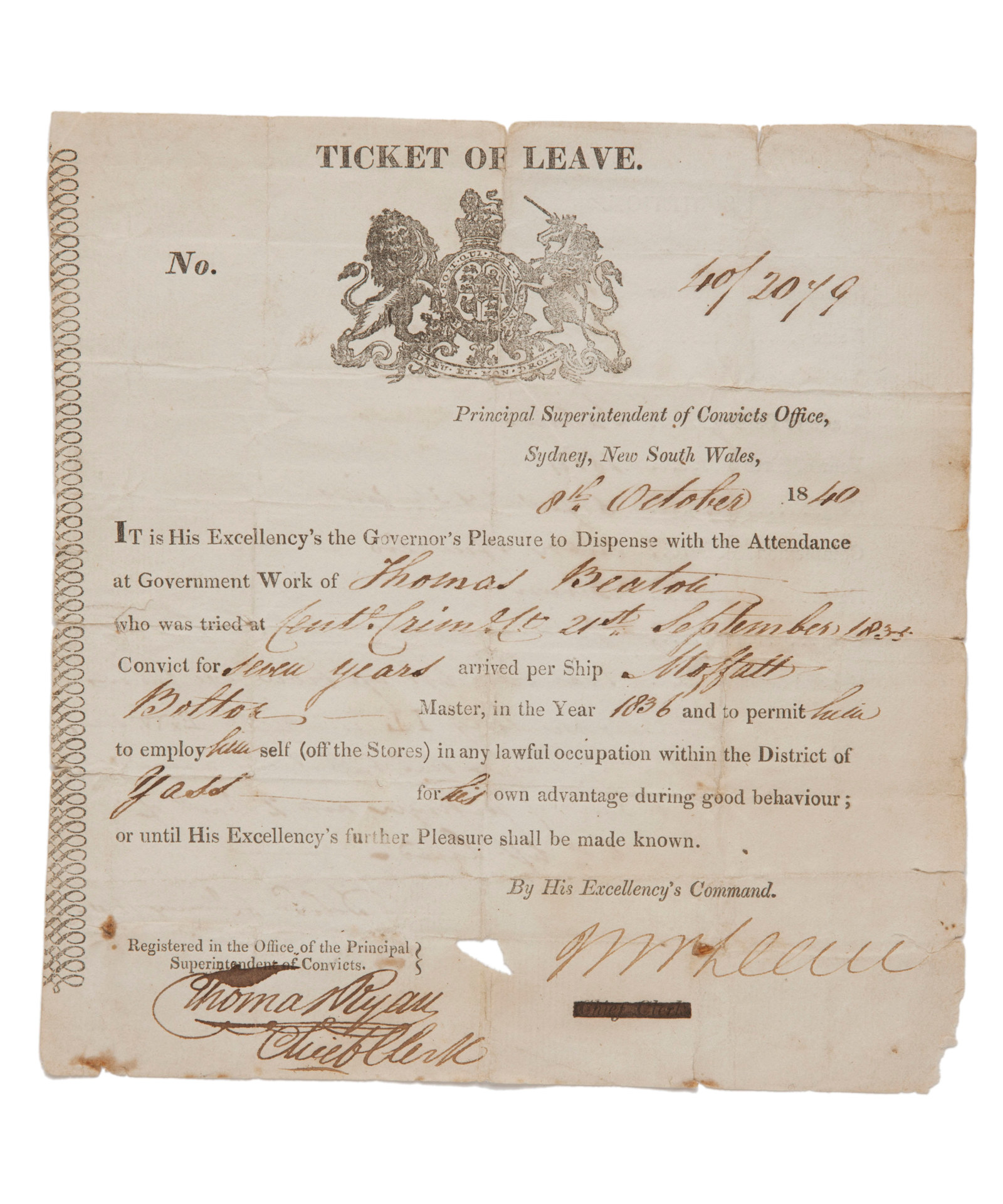

- Ticket of Leave – allowed convicts to work for themselves in a specific place, but they still had to follow rules and report to the authorities.

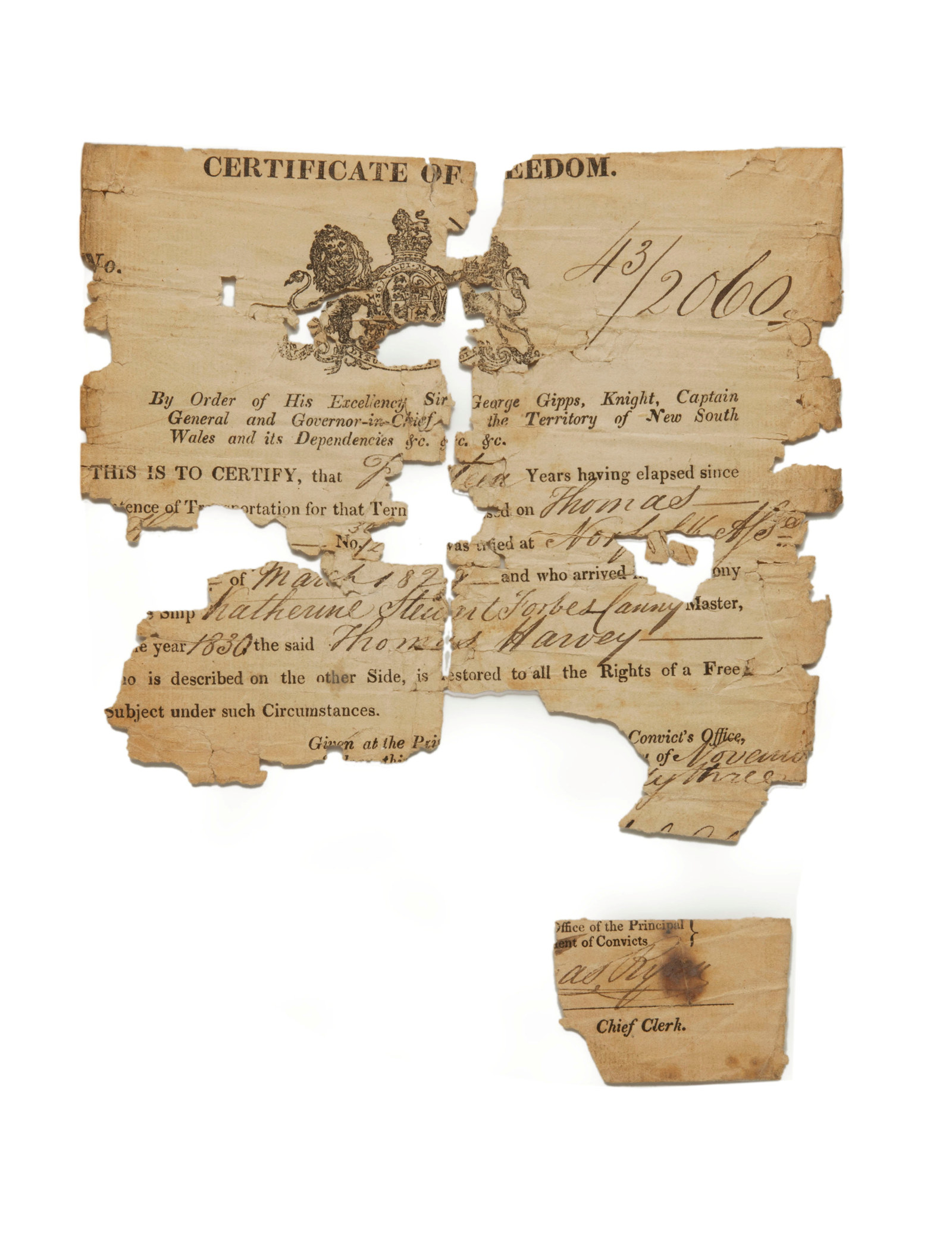

- Certificate of Freedom – given to convicts when they had served their sentence of seven or 14 years. This meant they were no longer a convict.

- Conditional Pardon – given to well-behaved convicts who had been transported for life. This allowed them freedom, but they were not to leave the colony.

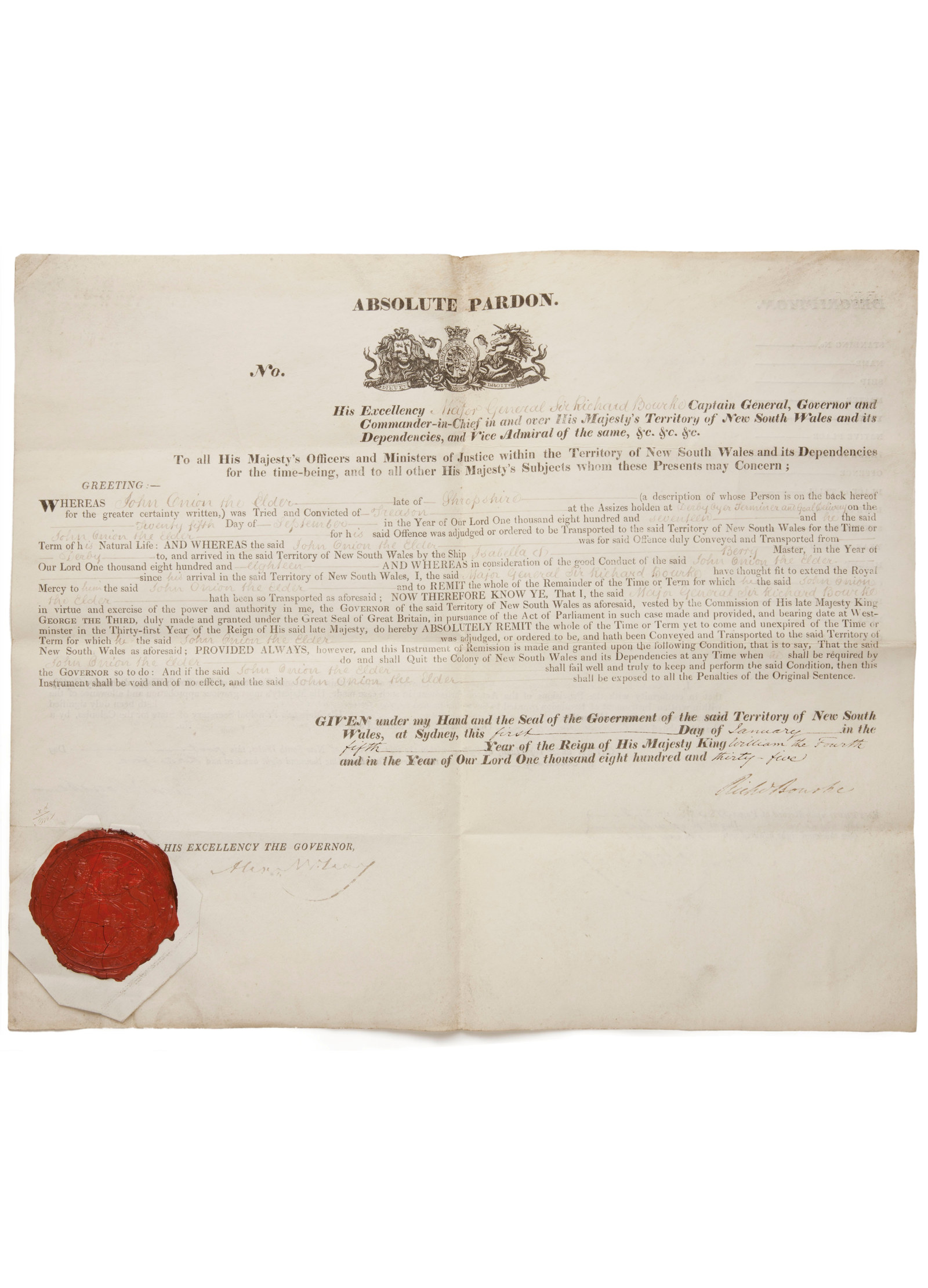

- Absolute Pardon – gave very well-behaved convicts complete freedom; they could stay in the colony or to return home.

- Royal Pardon – granted only by the monarch of England, these were very rare; they gave a convict complete freedom, to stay in the colony or to return home.

These documents had to be carried with the person at all times, to prove that they were free. The documents often included detailed information that identified the convict, including:

- place of origin (such as: London, England)

- age

- the year they arrived in the colony

- the name of the ship they were transported on

- hair and eye colour

- any scars, disabilities or tattoos.

Read more

Francis Greenway: the ‘future safety’ of the Rum Hospital buildings

When Sydney’s Rum Hospital was completed in 1816, the buildings were already showing signs of potential collapse, but newly-appointed Civil Architect Francis Greenway came to the rescue

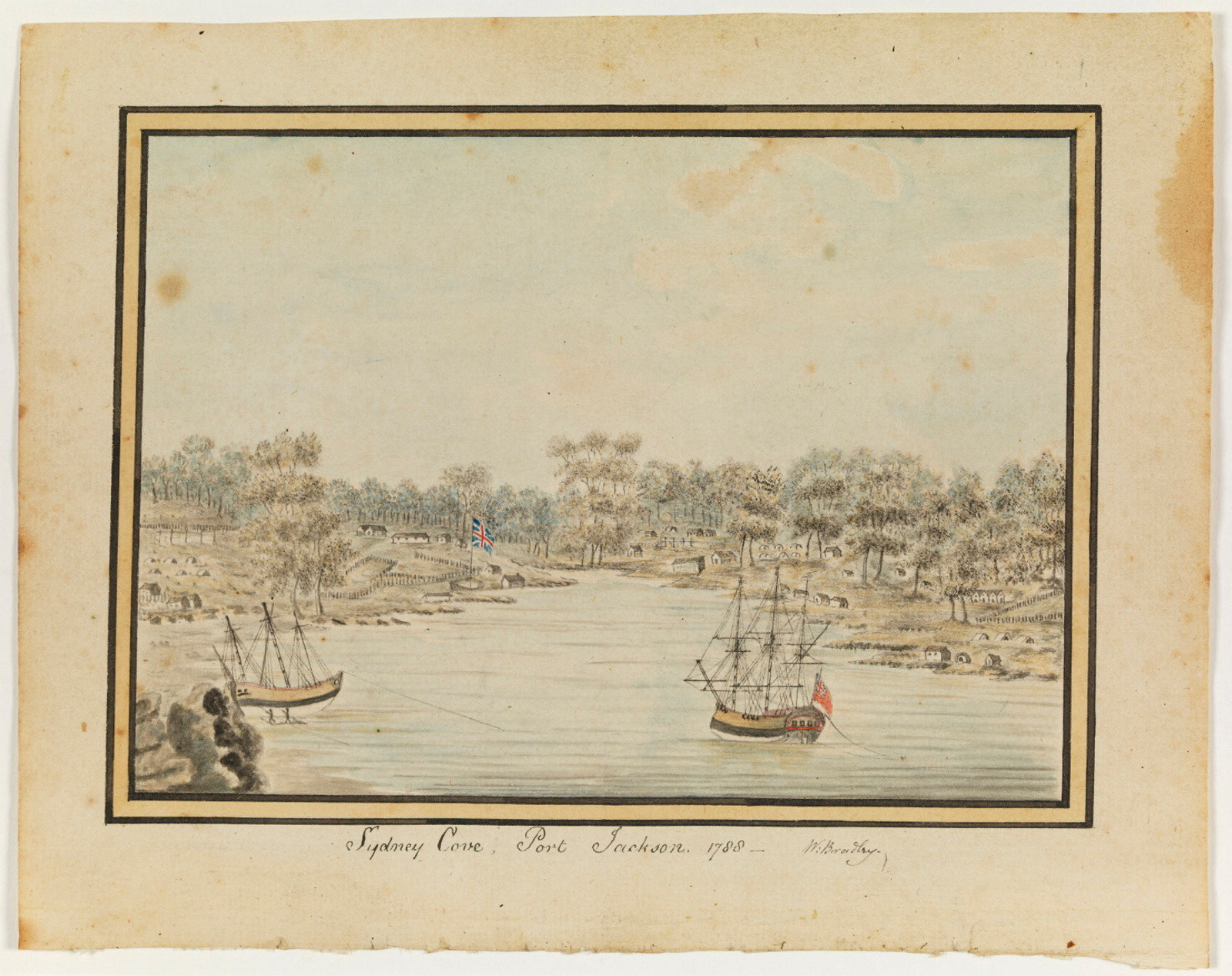

Convict Sydney

Ticket of leave

This Ticket of Leave granted to convict Thomas Beaton shows how well-behaved convicts could reduce the length of their sentences

Ticket of leave

During the early years of the settlement in Sydney, the government often gave convicts a ticket of leave if they were able to support themselves with work, or by growing food.

Some convicts – such as those who had been wealthy gentlemen back in England – were given tickets of leave as soon as they arrived!

However, this changed over time. In 1821 the governor ordered that all convicts had to serve a few years of their sentence before they could be given a ticket of leave, no matter how well-behaved they were.

This was usually:

- four years of a seven-year sentence

- six to eight years of a 14-year sentence

- ten to 12 years of a life sentence.

Once a convict was issued with a ticket of leave they did not have to work for the government anymore. However, they still had to follow certain rules. They had to:

- stay in the location written on the document (for example, Parramatta, NSW)

- obey government orders

- attend church each week

- report to the Hyde Park Barracks four times a month (if a convict lived further than 7 miles (11 kilometres) from the Barracks, they had to report to the local police station four times a month instead)1

If they broke any of these rules or committed another crime their ticket of leave could be cancelled. This meant they were convicts once again and had to work for the government.

In April 1826, Thomas Watkins’ ticket of leave was cancelled because he was involved in a crime.

A group of male convicts had stolen a load of wood and then sold it to Watkins. When they were caught, all the convicts were sentenced to wear leg-irons. But Watkins had his ticket of leave cancelled and so he lost his precious freedom.

Certificate of Freedom

A Certificate of Freedom was given to a convict once they had served their whole sentence of seven or 14 years. It was never given to someone who had been sentenced to life.

The certificate was a very important document, because it proved that he or she was now a free person – known as an emancipist (the term often used to describe a person once they were no longer a convict). A convict who was given one was allowed to leave the colony if they wanted to.

The certificate was split into two pieces.

One piece was kept by the government as a record of the convict’s reward. The other piece (called the ‘butt’) was kept by the person it was given to. They would carry it at all times as proof they were no longer a convict.

More than 40,000 Certificates of Freedom were awarded.

Read more

Convict Sydney

Certificate of Freedom

Certificates of Freedom had to be carried at all times and shown to the appropriate authorities on demand

Pardon me?

Convicts who had been sentenced to transportation for life were not eligible for a Certificate of Freedom. However, they could be awarded a ticket of leave and then, if they continued to behave well, a pardon.

There were three different types of pardon given to convicts with a life sentence.

Conditional pardon

A convict given a conditional pardon was free to work and travel anywhere in the colonies.

However, they were not allowed to return to Britain. Convicts given a conditional pardon could be given an absolute pardon at a late date.

Absolute pardon

An absolute pardon meant the convict was completely free. They could travel outside of the colony, including back to Britain.

An absolute pardon gave the convict back their full legal rights as a citizen and could be awarded at any time during their sentence.

Royal pardon

A few convicts were even rewarded with a royal pardon, authorised by the king or queen of England. These were quite rare, and awarded when the monarch decided to forgive the person for their crime, or the convict was found to be not guilty.

Convict Robert Mason received a royal pardon in 1837.

Mason arrived in Sydney in 1831, with 133 other convicts convicted of the same crime. He spent one month at the Hyde Park Barracks before being assigned to a free settler in the Hunter region.

He had been convicted of destroying farm machinery during the industrial revolution. This was called ‘machine-breaking’ and people did it because they were afraid that machines would replace them in their jobs.

Five years after he arrived as a convict he was pardoned. He married a female convict called Lydia Mills and lived in New South Wales for the rest of his life.

Read more

Convict Sydney

Absolute pardon

It must have been a proud moment for John Onion when he received this absolute pardon document in 1835

Convict Sydney

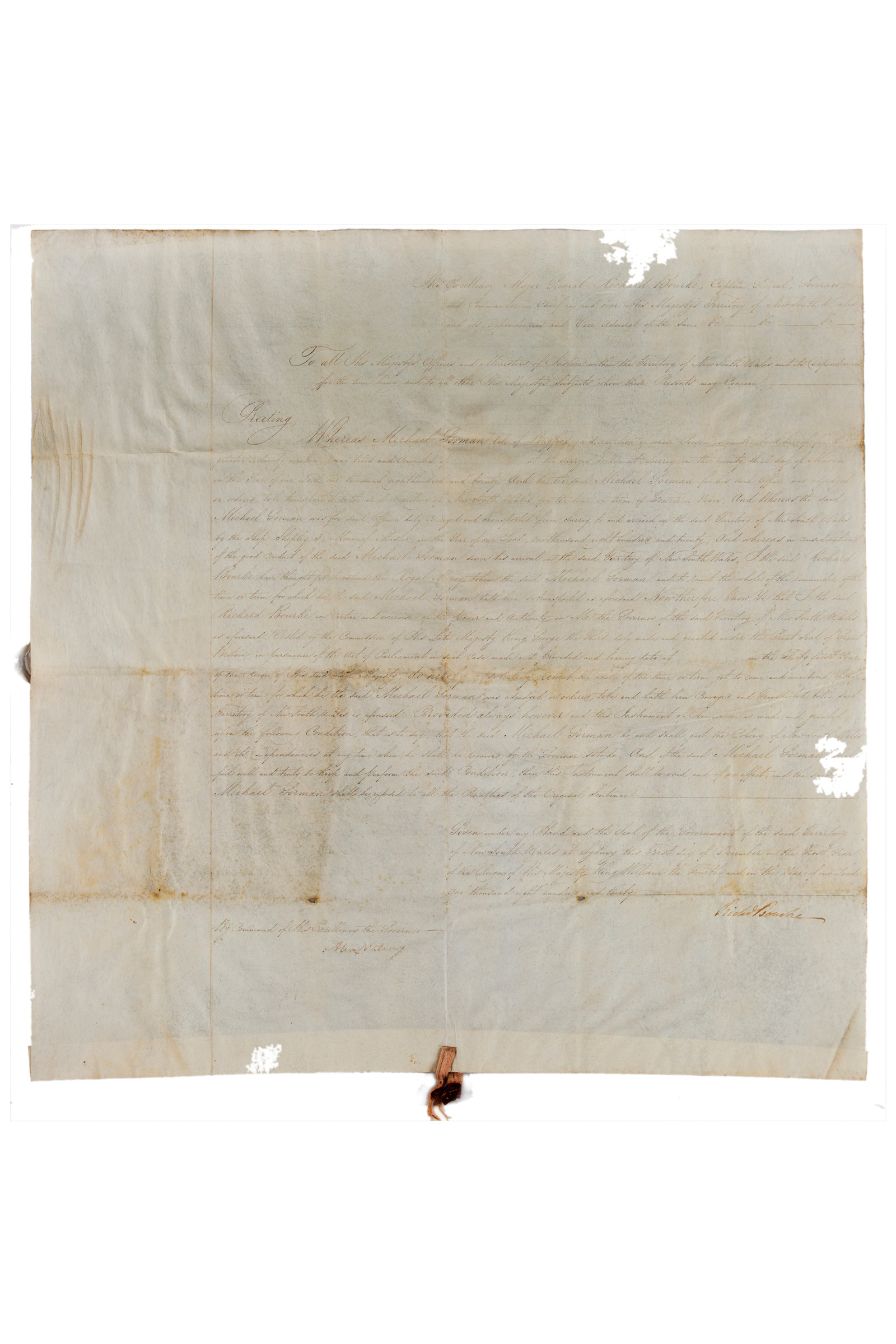

Absolute pardon

Convict constable Michael Gorman earned this absolute pardon in 1830/1832, for his service in the capture of the notorious bushranger John Donohoe

Footnote

1. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 15 April 1826, p1.

Related

Learning resources

Explore our range of online resources designed by teachers to support student learning in the classroom or at home

Convict Sydney

Convict Sydney

From a struggling convict encampment to a thriving Pacific seaport, a city takes shape

Why were convicts transported to Australia?

Until 1782, English convicts were transported to America, however that all changed after 1783

Resource

What clothes did male convicts wear?

The convict men who lived at Hyde Park Barracks were provided with a uniform to mark them as ‘government men’