Aboriginal Resources: administrative history

An administrative history of contact between the Government of New South Wales and Aboriginal people.

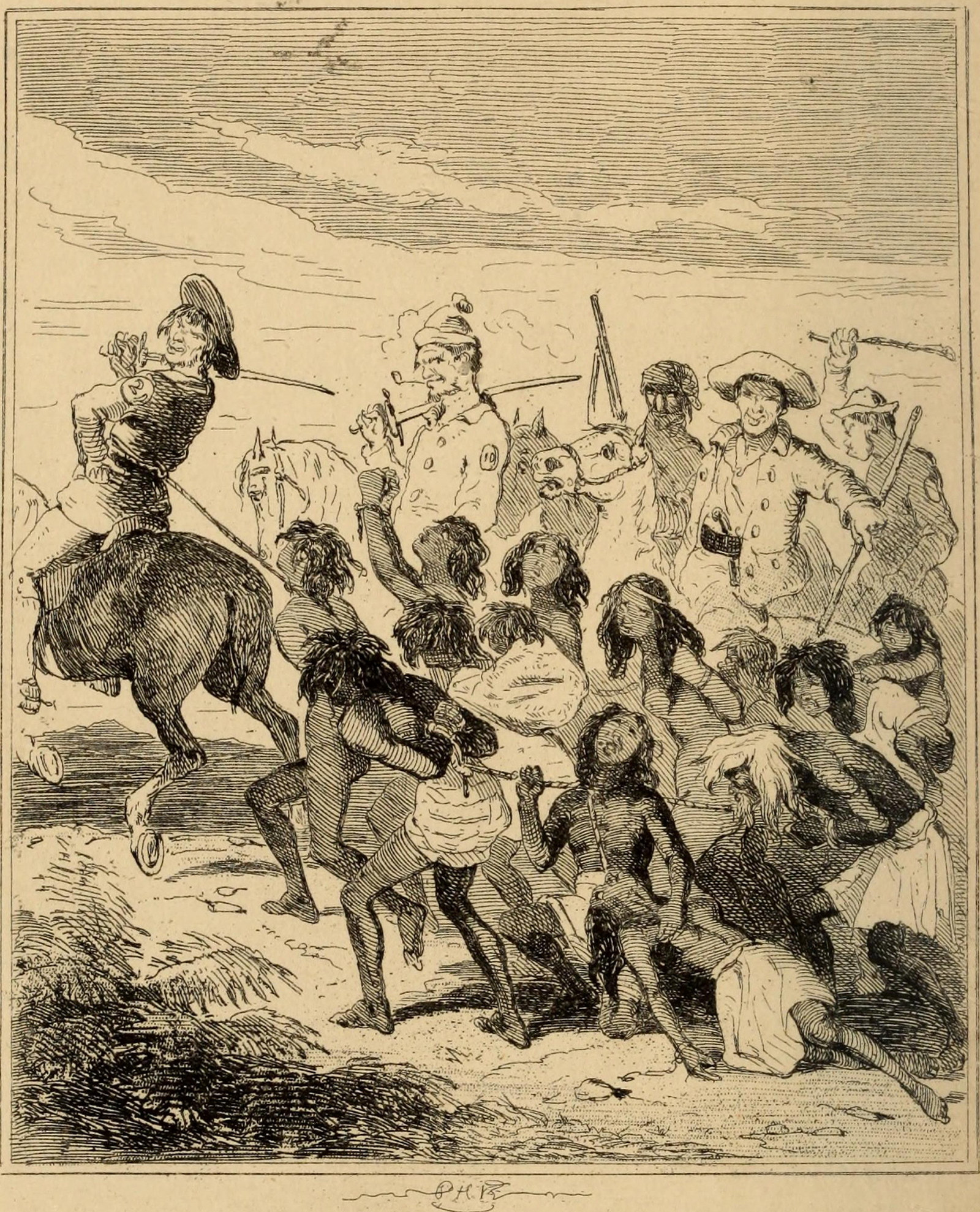

From first contact to Myall Creek

The record of the official policies of the Government of New South Wales from its establishment in 1788 is contained within the archives and public records of the State. Official contact with Aboriginal people has been continuous since 1788 and the first bureaucratic intervention came in 1815 when Governor Macquarie founded the Native Institution as a school for Aboriginal children of both sexes.1 The Government also subsidised missionary activity among the Aboriginal people, including that of the London Missionary Society in the 1820s and 1830s; the Reverend L.E. Threlkeld's Mission at Lake Macquarie being notable. Official activity was either benevolent, as in the distribution of boats and blankets by the authority of the Colonial Secretary, or aimed at control, as in the establishment of the Mounted Police and the Native Police.

The Myall Creek Massacre and protection

In 1838 following some violent clashes between Europeans and Aboriginal people, which resulted in massacres of Aboriginals, a Bill for the Protection of Aborigines was drafted, which contained provisions to protect ‘their just rights and privileges as subjects of Her Majesty the Queen.’2 1838 was also the year the Government of New South Wales, on instructions from the Secretary of State for the Colonies in London, instituted the short-lived experiment of a Protectorate of Aborigines based in Port Phillip.3 Funding for the Protectorate was cut in 1842, and it was abolished in 1849.

Until 1881 the main government agencies which dealt with Aboriginal people were the Colonial Secretary, Police and Lands Department.

In 1880 a private body known as the Association for the Protection of Aborigines was formed ‘for the purpose of ameliorating the present deplorable condition of the remnants of the Aborigine tribes of this colony.’4 Following agitation by this body, the Government appointed a Protector of Aborigines, Mr. George Thornton MLC.5

Related

Convict Sydney

Myall Creek massacre

On Sunday 10 June 1838, at least 28 Aboriginal people were massacred by a group of 12 Europeans at Myall Creek Station

The Aborigines Protection Board

A year later the Colonial Secretary and Premier (Alexander Stuart) in a Minute of 26 February 1883 created a Board for the Protection of Aborigines.6 This Board was to be ‘composed partly of officials and partly of gentlemen who have taken an interest in the blacks, have made themselves acquainted with their habits, and are animated by a desire to assist raising them from their present degraded condition.’7 The creation of the Board was ratified at a meeting of the Executive Council on 5 June 1883.8

The objectives of the Board were to ‘provide asylum for the aged and sick, who are dependent on others for help and support; but also, and of at least equal importance to train and teach the young, to fit them to take their places amongst the rest of the community.’9 The first members of the Board were three Members of the Legislative Council (including George Thornton, the former Protector), one private citizen (a lawyer), and two public servants. One of the latter was Edmund Fosbery, the Inspector-General of Police.

Around the same time the Government established the State Children’s Relief Board under the State Children Relief Act 1881 which had powers to remove children from charitable institutions, admit them to wardship and approve adoption of wards. This legislation set the scene for the future removal of Aboriginal children from their families.

The connection between the Board and the Police remained strong, with police representing the Board in most country areas, and also undertaking supervision of the reserves. The new Board also had the power to appoint Local Boards to aid the Board's business, which were, in most cases, comprised of local police and Police Magistrates. These Local Boards appear not to have been successful and were reconstituted by the Aborigines Protection Act 1909 (No. 25) into Local Committees. These were also deemed a failure as in 1915 they were ‘discontinued due to delays in administration and their failure to function expeditiously and were replaced by two Inspectors of Aboriginal Affairs.’10 The connection with the Aboriginal Protection Association was maintained, with the Board subsidising the Mission Stations which continued to be administered by the Association.11 In 1892, following a decline in public financial support, the Association turned over the management of these Stations to the Board.12

The policy of control and removal of children

In 1909 the Board was reconstituted and became a statutory body under the Aborigines Protection Act 1909 (No. 25). This happened because the Board felt they had ‘practically no authority over either the Aborigines or the Reserves set apart for their use, and it is very desirable that they should be clothed with sufficient powers to enable them to successfully carry out their work of endeavouring to ameliorate the condition of the race.’13

The Act specified that the Board would consist of the Inspector-General of Police, who would be ex officio Chairman, and not more than ten other members who would be appointed by the Governor. The functions of the Board were to apportion, distribute, and apply any monies voted by Parliament on behalf of Aborigines; to provide for the custody, maintenance, and education of the children of Aborigines; to manage and regulate the reserves; and to exercise a general supervision and care over all matters affecting the interests and welfare of Aborigines, and to protect them against injustice, imposition and fraud. The Act was proclaimed in the New South Wales Government Gazette to come into force on 1 June 1910.14 Under this Act the Board regularised and continued the policy of removing children from their families. In 1911 the Cootamundra Girls’ Home was opened to train Aboriginal girls for domestic service. Placement in the Home meant removal from their families.

In 1915 this Act was amended by the Aborigines Protection Amending Act 1915 (No. 2) which gave the Board further powers over apprentices and gave it the right to assure full custody and control over the child of any Aboriginal person, if after due inquiry it was satisfied that such a course was in the interest of the moral or physical welfare of the child.

The Act remained substantially the same until 1936 when the Aborigines Protection (Amendment) Act 1936 (No. 32) was passed, under which additional wide powers were conferred upon the Board. It consolidated the child removal sections and gave the Board complete power over the lives and future of every Aboriginal person in New South Wales.

Inquiries, agitation and a Welfare Board

In 1937 the Aborigines Progressive Association was formed, giving Aboriginal people their own vehicle for political debate and agitation. The same year the Legislative Assembly of the Parliament of New South Wales set up a Select Committee to inquire into the workings of the Aborigines Protection Board; and the following year the Public Service Board also held an inquiry into the Board.

The Sesquicentenary year of white settlement (1938), also saw the growth of the Aboriginal political movement, with the Day of Mourning and Protest being held on 26 January 1938. Soon afterwards the Committee for Aboriginal Citizens Rights was formed; and the Aborigines Progressive Association began to publish their journal, the Australian Abo Call, from March 1938.

In 1940 the Board was reconstituted by the Aborigines Protection (Amendment) Act 1940 (No. 12). This Act renamed the Board the Aborigines Welfare Board, and broke the nexus between the position of Chairman of the Board and Inspector General of Police. From then on the Chairman of the Board was to be ex officio the Under Secretary of the Chief Secretary's Department. The other members of the Board were: the Superintendent of Aboriginal Welfare (a Board official); an officer of the Department of Public Instruction; an officer of the Department of Public Health; a member of the police force of or above the rank of inspector; an expert in agriculture; an expert in sociology and/or anthropology and three nominated by the Minister. The Board's membership structure was changed once more in 1943 by the Aborigines Protection (Amendment) Act 1943 (No. 13) which provided for the appointment of two Aborigines to the Board. This Act also provided for the incorporation of the Board; and for exemptions from those parts of the Act which prohibited Aborigines from being supplied with alcohol. These liquor provisions were removed from the Act in 1963.

The 1960s saw a different kind of political activity with the Freedom Rides, modelled on the American Civil Rights movement, taking place throughout northern New South Wales. The Parliament of New South Wales also set up a Joint Select Committee on Aborigines welfare. As a result of this Committee’s Report, the Aborigines Welfare Board was abolished in 1969 by the Aborigines Act 1969 (No. 7).

After the Board

In place of the Board the Act created two new bodies, one administrative (the Directorate of Aboriginal Welfare), and one advisory (the Aborigines Advisory Council). The Directorate of Aboriginal Welfare was placed under the administration of the Department of Child Welfare and Social Welfare (later Youth and Community Services, now Community Services).15 In 1975 the Commonwealth Government took over the functions of the Directorate, which then became the Aboriginal Services Branch of the Department.16 In 1982 the Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs was created and took over the functions of the Aboriginal Services Branch.

The abolition of the Board meant that Aboriginal children under the care of the Board became wards of the State. Six years later in 1975 the title to Missions and Reserves in New South Wales was handed over to the New South Wales Aboriginal Lands Trust. In 1983 the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (No. 42) was passed.

The Department of Aboriginal Affairs is the successor agency to the Board and consequently retains the right to set the access conditions for the records.17 It does this in consultation with the Archives Authority, specifying that any person who wishes to see the records must consult with the Department first. These decisions on access are made by Aboriginal people within the Department of Aboriginal Affairs after consultation with Aboriginal organisations, the responsible Minister and the Archives Authority.

Chronology of events

Aboriginal resources: chronology of significant events

This chronology gives an overview of significant events which have happened in Australia from 1788 to 1998, concentrating on the relations between Aboriginal people and the post-1788 immigrants

Notes

- Supreme Court: Miscellaneous Correspondence relating to Aborigines; Government and General Order of 14 December 1814 SRNSW: [5/1161. Copy at COD 294A]; the New South Wales Government Submission to the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families, March 1996, has a useful Chronology on pages 3-6. This Submission is also a detailed history of official administrative contact with the Aboriginal people.

- Colonial Secretary: Copies of Minutes and Memoranda Received, 1838 SRNSW: [4/1013]. This bundle also contains policy drafts, Minutes, and correspondence relating to land rights sovereignty, and conflict between British settlers and Aboriginal people. Copies of the Bill are also in the New South Wales Parliamentary Archives.

- Historical Records of Australia, Series 1, Volume XIX, pp.252-255. Despatch No. 72 dated 31 January 1838.

- New South Wales Aborigines Protection Association, Report 1881-1882, Sydney, 1882.

- New South Wales Government Gazette, 30 December 1881, p.6816; Colonial Secretary: Copies of Minutes and Memoranda Received, 1882, Minute No. M18310 of 3 January 1882 in Colonial Secretary In Letter 82/98 SRNSW: [1/2523].

- Colonial Secretary: Copies of Minutes and Memoranda Received, 1883, Minute No. M18452/2 SRNSW: [1/2542].

- ibid.

- Executive Council: Minute Books, Volume 23, Minute No. 21, 2 June 1883, p.58. SRNSW: [4/1570]; New South Wales Government Gazette, 5 June 1883, p.3087.

- Aborigines Protection Board, Annual Report, 1885, p.3, in New South Wales, Votes and Proceedings of the Legislative Assembly, 1885, Volume 2, p.605.

- Public Service Board, Special Bundles: Report and Recommendations of the Public Service Board on Aborigines Protection, 1940, p.8. SRNSW: [6/4501.1]; Manuscript original is in the Chief (Colonial) Secretary’s Special Bundles, 1938 SRNSW: [4/8565.2]; also printed in New South Wales, Parliamentary Papers, Session 1938-39-40, Volume 7, pp.739-786.

- The stations were Cumeragunja, Warangesda, Maloga, and (later) Brewarrina.

- Aborigines Protection Board, Annual Report, 1892, in New South Wales, Votes and Proceedings of the Legislative Assembly, Session 1892-3, Volume 7, pp.1144-1155.

- Letter from the Secretary of the Aborigines Protection Board to the Under Secretary of the Chief Secretary’s Department in Colonial Secretary In-letter 09/102 SRNSW: [5/7030]. The subject of the letter was the definition of the word “Aborigine” in the draft Bill.

- New South Wales Government Gazette, 11 May 1910, p.2486.

- Report of the Minister for Social Welfare on the workings of the Aborigines Act, 1969, for the year ended 30 June 1970, pp.6-7, in New South Wales, Parliamentary Papers, Session 1969-70-71, Volume 1, pp.6-7.

- Department of Youth and Community Services, Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 1976, p.32, in New South Wales, Parliamentary Papers, Session 1976-77-78, Volume 12, p.1285.

- The Department was established in 1995. New South Wales Government Gazette, Special Supplement, 5 April 1995, p.1859 and p.1860.

First Nations

Browse allAboriginal resources: an overview of records

A brief overview of the State archives that document the NSW government's interaction with Aboriginal people from 1788 until today

Aboriginal resources: a guide to NSW State archives

A listing and description of records in our collection which relate to Aboriginal people

19th Century Aboriginal population records

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are respectfully advised that our collection may contain images or names of deceased people in photographs or text. We acknowledge that language in the records referring to Aboriginal people may be confronting and in some instances would be considered offensive if used today.

Aboriginal trackers & gaol photos

This webinar highlights records that Aboriginal people can access to discover more about their own family history on the colonial frontier