The bombing of Bangoola: being German in Sydney during World War I

Sometime in 1912, Paul Schreiterer (1868–1939) and his family decided to have their comfortable home, Bangoola, located in the Sydney suburb of Mosman, photographed for posterity.

The photographs suggest the story of an immigrant’s success. Paul Schreiterer had arrived in Australia from Germany as a young man in 1893. He found lucrative work as a wool buyer, married Australian-born Ida Smith (1874–1953), raised six children and built a substantial home with harbour views. But the languid calm suggested in these Bangoola photographs was, for the Schreiterer family, transformed in a most confronting way with the coming of World War I.

At 1.57am on 6 January 1917 a ‘large gelignite bomb’ was thrown into the basement of the Schreiterers’ home and ‘exploded with great violence’, according to The Sun newspaper.1 The family were fortunate to escape injury despite the force of the explosion throwing two of the children from their beds. The sound of the bomb was heard as far away as Cremorne Point and caused a crowd to quickly gather near Bangoola. Those who arrived early would have witnessed a dazed Paul Schreiterer and family emerging from the damaged home.

The house was saved from being blown off its foundations only because of its substantial bulk. Nevertheless, the bomb, thrown through a ventilator under the verandah, caused considerable damage. Heavy floor joists were lifted and the timber verandah flooring wrecked, every front window was broken, the piano in the parlour was thrown out of position, valuable china and glassware was smashed and a pendulum was blown off the grandfather clock.

Despite a police investigation and the offer of a £100 reward, no arrests were made for the bombing of the Schreiterers’ home. Although Paul Schreiterer stated that he had no known enemy, German Australians were exposed to considerable abuse and even physical violence from many sectors of the community during World War I. Almost a year earlier, in February 1916, a similar incident occurred when an explosive was thrown through an open fanlight of the Mosman bakery of German-Australian Otto Pfafflin. No one was injured but the shop was wrecked, and as with the Bangoola bombing, police made no arrests. Pfafflin, a pastry cook, was German born but had lived in Australia for over 30 years, married an Australian-born woman and raised four children.2

Before the war, German nationals formed the largest non-British ethnic group in Australia. Australians with German ancestry had integrated well into the community. All that changed with the war. The publication of Australian casualty lists, especially after the Gallipoli landing in April 1915, had a devastating effect on many families, and the sinking of the passenger liner Lusitania by a German U-boat in May 1915 with the loss of 1198 lives galvanised feeling against anyone associated with Germany.

‘All Germans and persons of German origin were looked upon with suspicion’, according to Ernest Scott, author of Australia during the war, one of the official histories of Australia during World War I.3 In fact, the definition of who was a ‘German’ – and conversely, who was an ‘Australian’ – was contentious for both the community and the government during the war. Although he took an oath of neutrality at Mosman on 14 August 1914, Paul Schreiterer had never become a naturalised Australian. He was classified by the Commonwealth Government as an ‘enemy alien’, and his Ballarat-born wife was also classified as German, having lost her Australian citizenship on her marriage to a non-national. Ida’s application for readmission to British nationality was refused in February 1915. The Schreiterer children were also considered enemy aliens when the definition expanded in May 1916 to include Australian-born children and grandchildren of those born in countries at war with Australia.

As the war progressed, accusations of anti-Allied activities were increasingly made against German Australians. An extensive dossier was compiled about Paul Schreiterer by the Special Intelligence Section attached to the Australian defence forces. One report prepared in October 1917 observed that ‘hardly a month passes without some communication, mostly anonymous, being forwarded accusing him [Schreiterer] of behaving in a suspicious manner’. Schreiterer’s file itemised allegations by various members of the local community accusing him of espionage, of secretly signalling at night to another German Australian and to having other ‘Germans’ over to his house with whom he celebrated ‘at every reverse of the Allies’.4 The police investigated every allegation, interviewing neighbours of the Schreiterer family and other people in the Mosman community. Despite all this effort, no evidence of any wrongdoing was ever uncovered. The dossier reveals that following investigations, ‘it has always appeared that the people who ought to have been able to give the information [about Schreiterer] knew nothing about the facts alleged and referred to other people who were just as ignorant’. Indeed, despite numerous allegations of spying, sabotage or hindrance to Australia’s war effort by German Australians, no claims were ever substantiated. Military intelligence blamed the Mosman branch of the Anti-German League for the false allegations against Schreiterer. The branch, according to one officer, was composed of ‘several highly neurotic women’.

Thirty-two branches of the Anti-German League were active throughout NSW during World War I. The Mosman branch, established in October 1915, met twice a month to listen to talks and discuss the latest campaigns, such as support for the pro-conscription referendums. The ‘Platform & Objects’ of the branch advocated the internment of all enemy aliens and stated that all persons of ‘enemy origin’ should lose particular entitlements of Australian citizenship such as the right to vote, to be elected to any Australian parliament or to take up Crown land.5 From its earliest days, the Anti-German League also urged the dismissal of all German Australians employed in Australian public, naval or military services. The Mosman branch, however, took their activities a step further, acting as a self-appointed investigative agency into the activities of local German Australians.

The Mirror was probably the most strident anti-German newspaper published in Australia during World War I. Under the headline ‘Germans live in luxury whilst Australians perish’, the article listed the names, addresses and activities of a number of allegedly suspicious German Australians. Some lived in or around Mosman, and a number were involved in the wool trade like Paul Schreiterer and so were probably acquaintances. The two German Australians who owned ‘Hun homes’ at Neutral Bay were also in the wool trade and were relatively close neighbours of the Schreiterer family.

At a meeting of the Mosman branch of the Anti-German League in December 1916, just a week before Bangoola was bombed, the principal business concerned the behaviour of a suspicious local group known to members as ‘Little Berlin’.6 Although the membership of ‘Little Berlin’ is unknown, the group may well have included Paul Schreiterer and his German-born neighbours and colleagues. When investigating one of the allegations against Schreiterer, Sergeant G E T Pollard of Mosman Police noted that since the outbreak of war, ‘the German population of Mosman has been ostracised by their former British friends, consequently bringing the Germans more in touch with each other’.7 In addition, Paul Schreiterer probably found himself spending more time at home in Mosman than he had before the war, as his employment dried up when German-owned wool broker and import/export firm Lohmann & Co was shut down by the Australian government under the Trading with the Enemy Act

After the bombing of Bangoola, the remainder of the war cannot have been a comfortable time for the Schreiterer family. Although anti-German feeling against German Australians continued until well after the war ended, the family continued to live in Mosman, and both Paul and his son Claude applied for and were granted Australian citizenship in the early 1920s. The Schreiterers had German roots but the family clearly saw their future as Australians. Paul lived in Mosman until his death, at home at Bangoola in April 1939 – just a few months before another world war would bring unhappy consequences for the next generation of German Australians.

Footnotes

1. ‘Bomb outrage: explosion at Mosman’, The Sun, Sydney, 7 January 1917, p4.

2. ‘Supposed bomb: explosion at Mosman’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 February 1916, p10.

3. Ernest Scott, Official history of Australia in the war of 1914–1918, vol XI, Australia during the war, Angus & Robertson Ltd, Sydney, 1936, p106.

4. National Archives of Australia: Special Intelligence Bureau, New South Wales; ST1233/1, Investigation files, single number series with ‘N’ [New South Wales] prefix; N45339, Paul Schreiterer [Box 158], 1915–1932.

5. State Records NSW: Premier’s Department; NRS 12060, Letters received, 1907–1976. [9/4849] 20/634 enclosing ‘Platform & objects of the Anti-German League, Mosman Branch’, nd.

6. ‘Anti-German League’, The Mirror, Sydney, 30 December 1916, p2.

7. NAA, ST1233/1, N45339, Paul Schreiterer [Box 158].

Published on

More

On This Day

17 Dec 1915 - 'Waratah' recruitment march

On 17 December 1915 the "Waratah" recruitment march arrived in Sydney

WW1

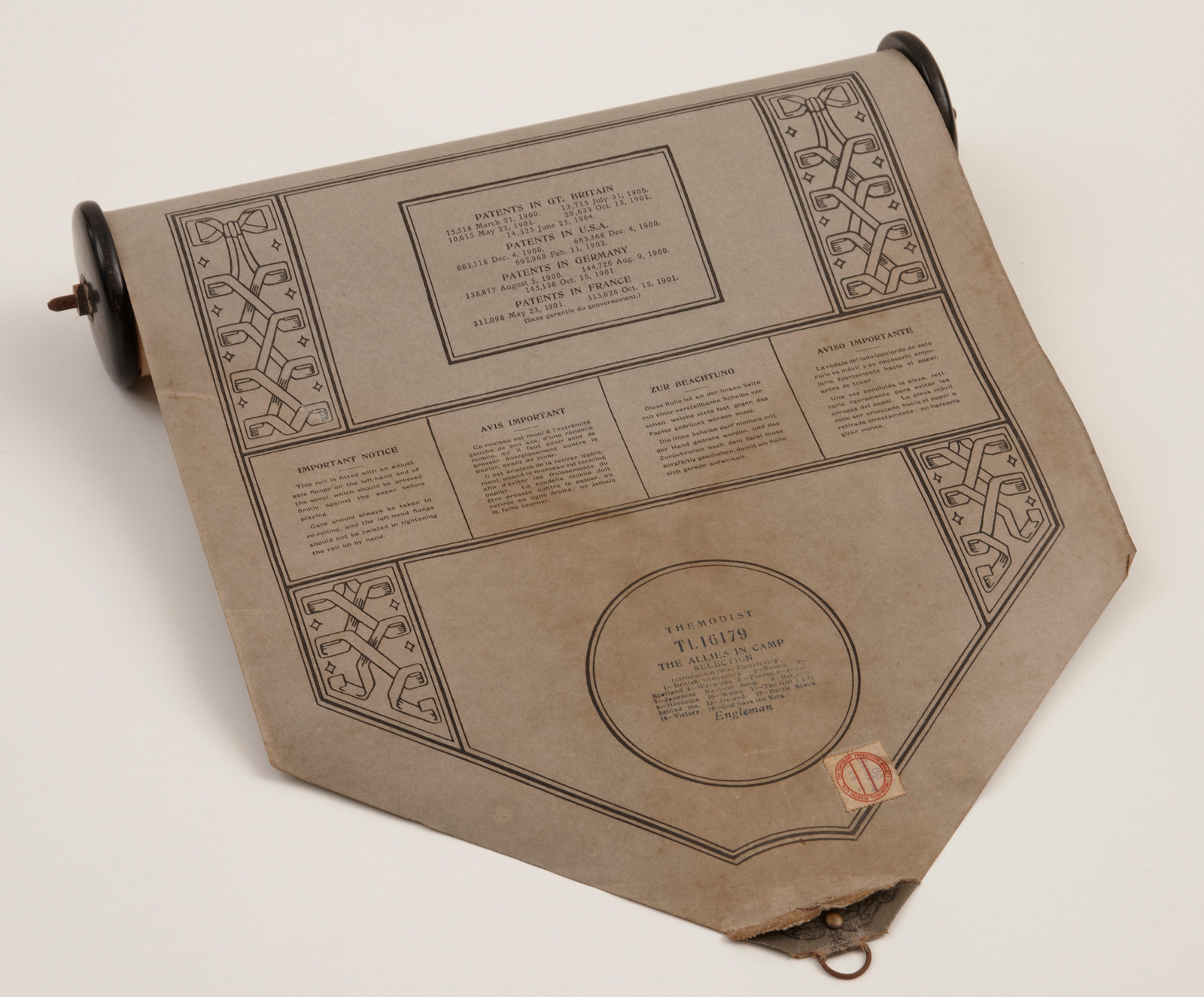

The Allies in camp music roll

Rouse Hill house boasts a fine pianola, a player piano, which came into the house just a few years before the outbreak of World War I

WW1

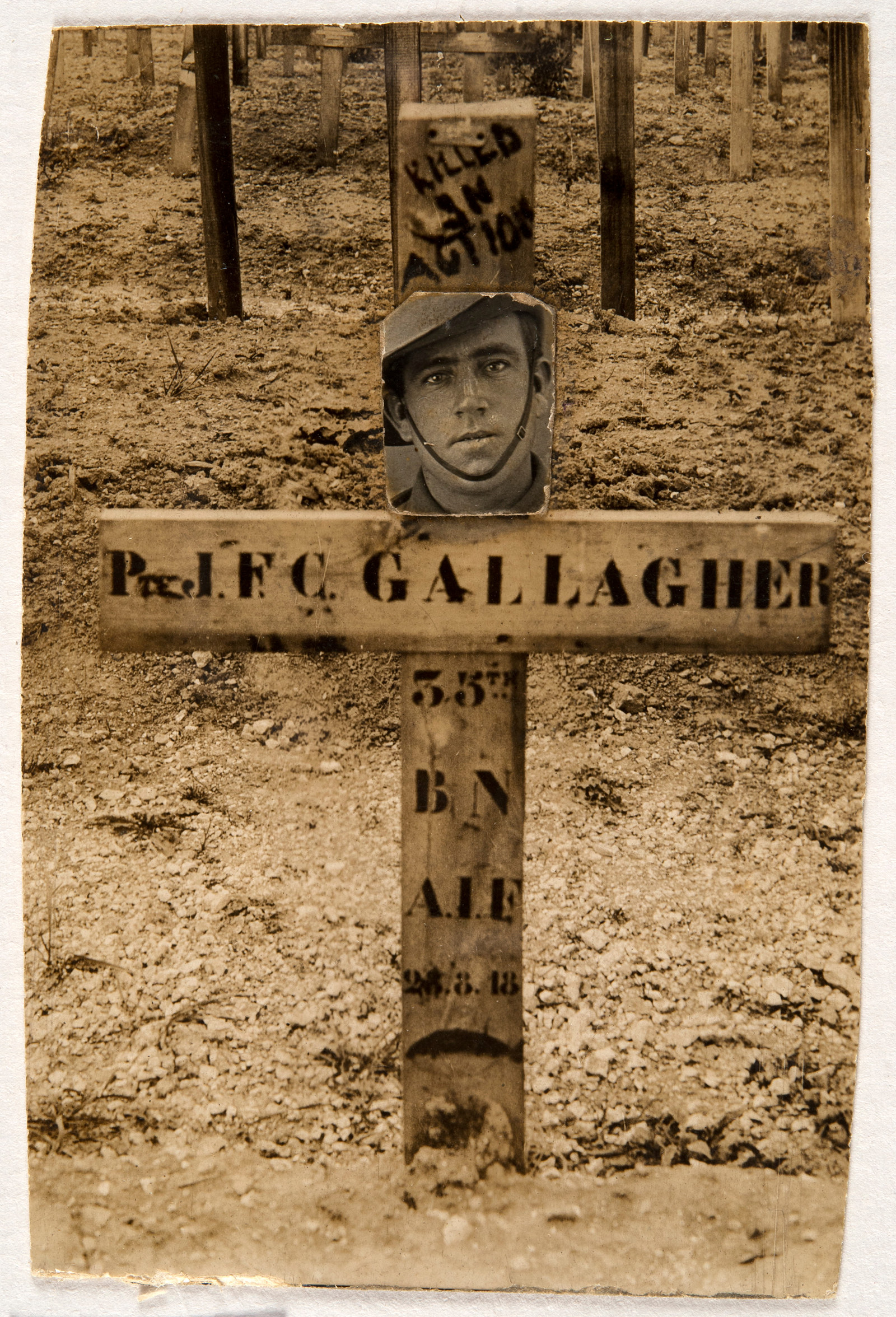

Frank Gallagher’s grave markers

Late in the afternoon on 23 August 1918, Private John Francis Cecil Gallagher, known as Frank, was killed by shellfire at 23 years of age

WW1

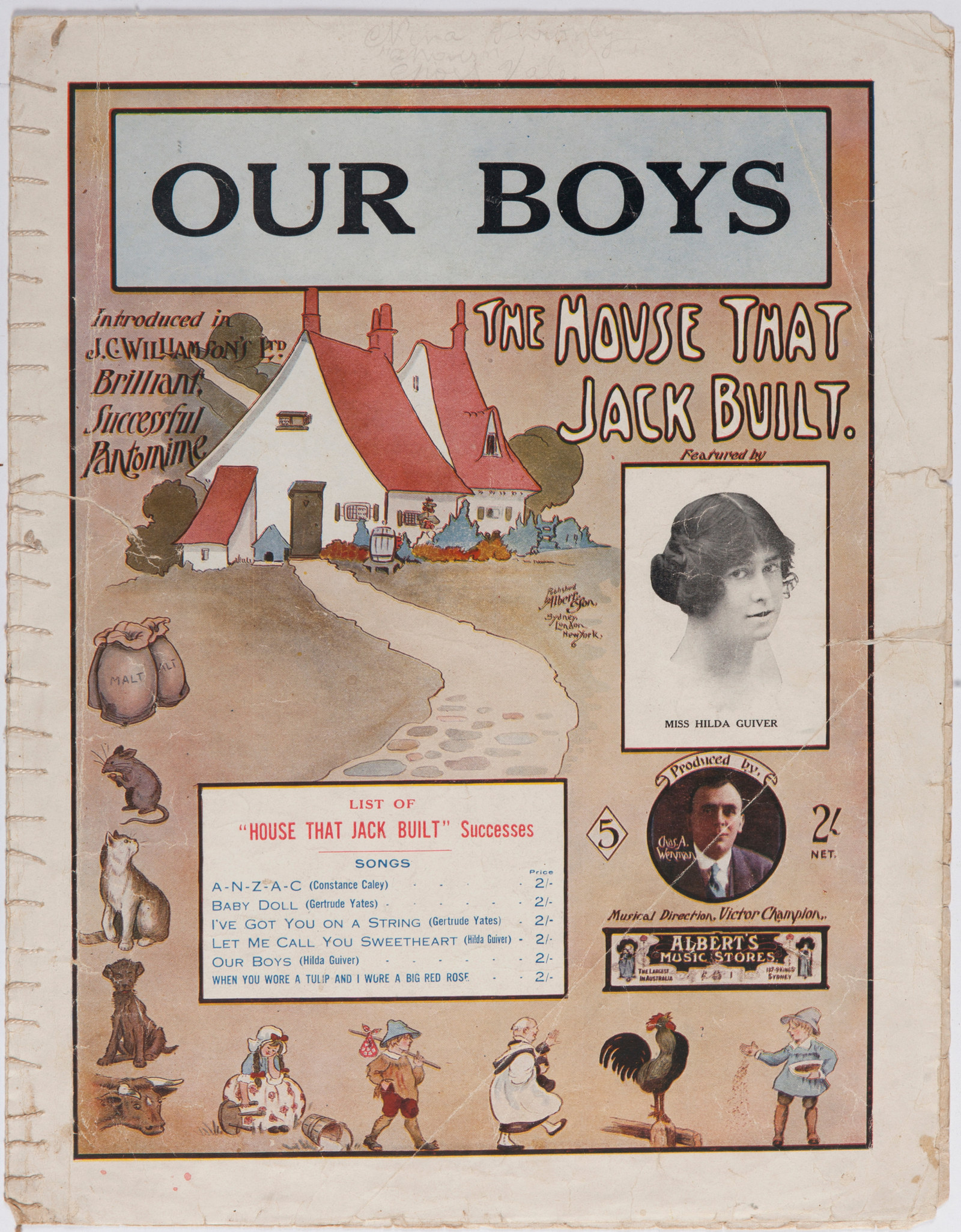

Our Boys: patriotic sheet music

The song, written by a young Sydney woman named Evelyn Greig, was one of more than 500 patriotic songs published in Australia during World War I