If these walls could talk: The Mint

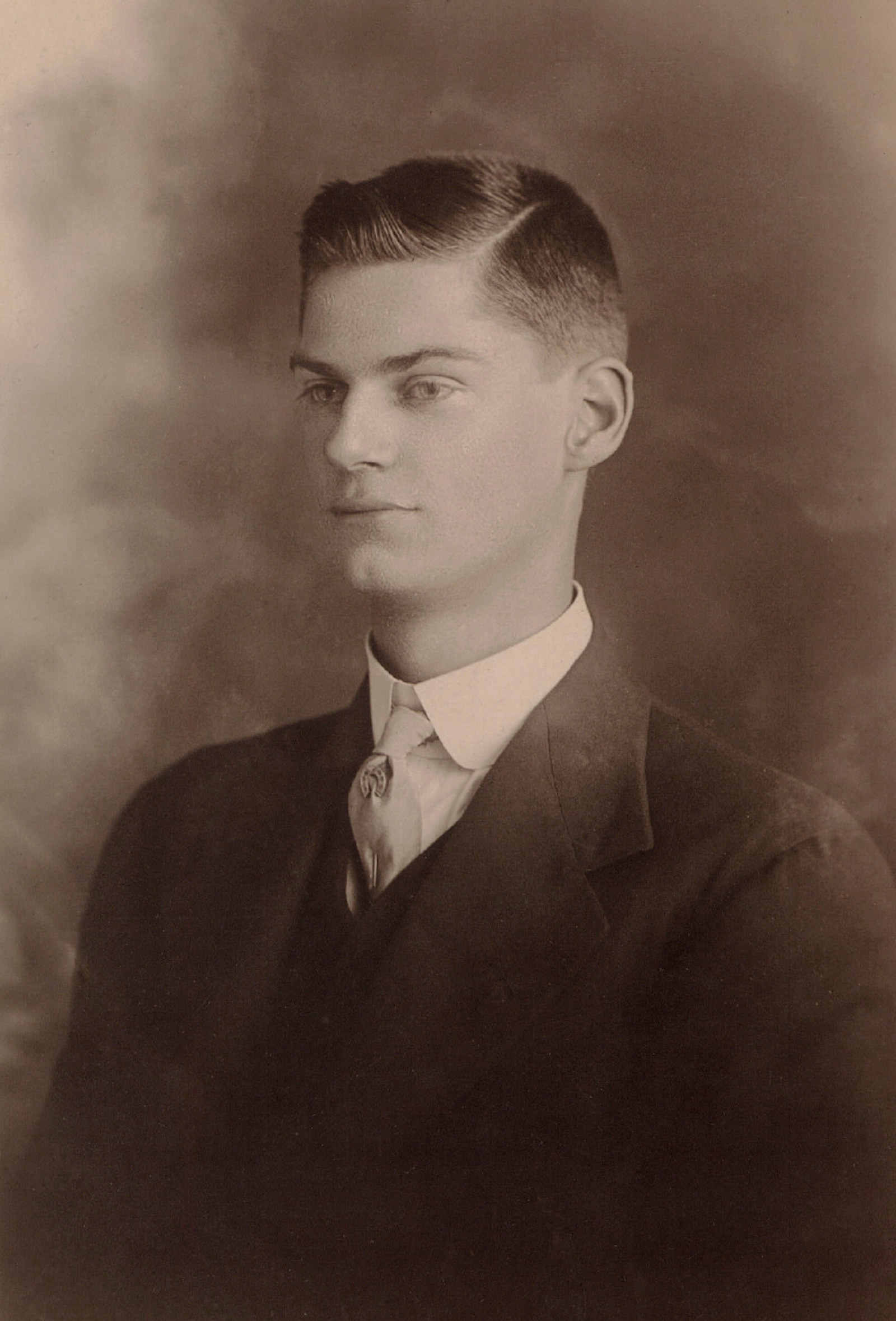

Charles Miller, Frederick Sydney Hoptroff, Arthur Kilgour, Edgar Upton, Oliver Whiting, Theophilus (Theo) Bowmaker and John Gilchrist were all employees of the Royal Mint’s Sydney branch. Between 1914 and 1918 they enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force and their service is remembered with an honour board that hangs in the southern stair hall of The Mint.

Working-class soldiers

Six of the men were ‘workmen’, permanent employees whose wages increased with experience. Charles Miller started at the Mint in 1904, and by 1914 he was an accomplished third class workman earning 8 shillings a day. The lure of adventure or a sense of duty must have been compelling, because in December of that year he became the first Mint worker to enlist.

Theo Bowmaker, who started as a junior clerk in 1896, was the only white-collar employee among the men. By 1916 he had accumulated 20 years’ employment and had an annual salary of around £300. Yet he too was drawn to war. Leaving behind a secure job and a wife, he enlisted in 1916 at the age of 39.

Before embarking for war the men would have undertaken hours of drill and rifle training, and learned skills relevant to their various positions in the army. As privates they earned 6 shillings a day, so none benefited financially from enlisting. The Mint’s deputy master agreed to make up any shortfall, ensuring the men received the equivalent of their full Mint pay while serving in the army.

Life on the front line

Within a week of moving to the front Arthur Kilgojjjur’s nerves were strained. He served with a Field Ambulance unit, carrying stretchers and giving basic first aid to wounded soldiers. In his diary he records his experiences of witnessing death and sadness and of almost being blown apart by a German shell. He confesses his struggle to give up gambling for the sake of his wife-to-be back home and recounts losing a wristlet watch (a present from Sydney Mint staff) in a French hayloft.

Went through the gas test this morning … Chlorine gas. Once again memories of the Mint came flooding back to me, of how the Chlorine gas affects so many of the [Melting] House staff.’

Arthur Kilgour, diary entry, 27 July 1916

Kilgour describes undergoing training to survive a gas attack, an experience that left a deep impression on him: ‘Went through the gas test this morning … Chlorine gas. Once again memories of the Mint came flooding back to me, of how the Chlorine gas affects so many of the [Melting] House staff’. Chlorine was used at the Sydney Mint as part of the gold purification process.

Woven among these accounts of the difficulties of life on the front line are tales of ‘skylarking’ with mates, mud-fights and hunting for blackberries. Kilgour saw spectacular aeroplane duels high above the trenches, voted ‘no’ in the 1916 conscription referendum and enjoyed life’s simple pleasures whenever he could: ‘Had another swim in the Ancre River this evening’, he wrote in May 1917. ‘It was tres bon.’

Another mud fight this afternoon. If the folk at home were to see us skylarking they would think we had gone mad.

Arthur Kilgour, diary entry, 11 December 1917

Mint men and proud of it

Kilgour did not lose his identity as a Mint man while abroad, visiting London’s Royal Mint at least twice. ‘Went over, by appointment,’ he wrote in November 1917, ‘the foreman of the Coining Room remembered me from last time. We had a great little chat’. Neither did he forget the men he had worked alongside in Sydney, catching up behind the lines with one of his old colleagues and hearing news of others: ‘Met … Hoptroff from the Sydney Mint. What a grand old chat we had of old times. If we do not go up the line tomorrow Sid is coming down to me’ and ‘This afternoon I went down to tea with Sid Hoptroff. Our old friend Oliver Whiting of the Sydney Mint has been killed in action. The news has fairly stunned me’. Whiting was killed in 1917, a week before his 20th birthday.

Returned servicemen

Miller served at Gallipoli and in France, and returned to the Mint in 1919, re-entering the workforce as a second class workman on 10 shillings a day. Bowmaker was badly wounded in the leg and was discharged from the army. By 1924 he was head of the Coining Branch, overseeing Miller, as well as Upton, Kilgour and Hoptroff, who all returned to the Mint after their wartime service. Gilchrist went back to work in the Melting and Refining Branch. Hoptroff resigned from the Mint in 1924 to take up a job with the Telephone Department; the rest of the men remained at the Mint until it closed in 1926.

The author acknowledges the following as a key reference for this article: Diary of Arthur McPhail Kilgour (Private, 1st Australian Field Ambulance and then 2nd Battalion): diary extracts detailing service in France between July 1916 and November 1918. Australian War Memorial, private record.

Published on

The Mint stories

Browse all

Unexpected views

Over the decades, photographers have captured unexpected glimpses of the Mint’s history

Museum stories

The changing face of the Mint

As photographers documented the evolving face of the Mint, they recorded changes to the site and streetscape