Convict farmer Antonio Roderigo and a ‘dastardly massacre’

A dispute over potatoes farmed by convict-settler Antonio Roderigo was one of many hostile events between colonists and Wiradyuri people that led to the Bathurst War of 1824. Curator Dr Jacqui Newling has traced Roderigo’s story through the archives.

As the NSW colony expanded beyond the Sydney basin in the 19th century, conflict and violence between colonial settlers and Aboriginal people became more frequent. Many incidents were not formally documented. One such incident occurred in 1824 after a group of Wiradyuri harvested potatoes grown by convict farmer Antonio Roderigo. Roderigo’s response resulted in several Wiradyuri people, including women and children, being injured or killed by local colonists. The earliest written record of this ‘dastardly massacre’ dates to the 1880s, in a memoir by William Suttor, who farmed at Brucedale, near Bathurst.1 The account offers scant detail, but members of the local community understand that among those killed were Watamara (or Worima), the wife of renowned Wiradyuri leader Windradyne, and one of their sons.2 Sometimes referred to as the ‘Potato Field Incident’, the conflict was a catalyst in the escalating series of clashes between Aboriginal people, including Windradyne, and colonists, many of them poorly supervised convicts or ex-convict settlers who acted as vigilantes against local people.

An ‘alien’ convict

Documents held in the State Archives Collection and other historical sources have helped us to piece together the story of Antonio Roderigo, who came to Bathurst in 1815 as an assigned convict. Believed to be Portuguese, Antonio Josea Roderigo (also Rodrigo, Roderick) was one of many ‘alien’ (non-British) convicts transported to Australia in the early 1800s. Aged about 30, he was tried for burglary at Winchester, Hampshire, in the south of England, in March 1810.3 He was sentenced to death, but this was commuted to transportation for 14 years. He arrived in the colony on 29 September 1811, on the Admiral Gambier, and was sent into private assignment in Sydney.

Roderigo worked under assignment for ex-military officer William Cox from about 1812. In 1815 he became a stockman on Cox’s newly granted property – 2,000 acres (809 hectares) situated across the river from present-day Bathurst. Cox was the first person to be granted land in the region, in recognition of his role supervising the construction of the roadway through the Blue Mountains, which facilitated the colonisation of the land beyond, in Wiradyuri Country. Cox did not live on the property, which he named ‘Hereford’, but he ran sheep and grew wheat there, relying on workers (including Roderigo) to tend the land and his flock.4 In his work for Cox, Roderigo was one of Bathurst’s founding convict ‘settlers’.

By 1819, having served eight years of his sentence, Roderigo applied for mitigation, most often granted in the form of a ticket of leave, which would enable him to live independently but with restrictions and reporting conditions, in a similar fashion to the parole system today. Roderigo’s testimonial to the governor stated that ‘during his residence in the colony [he had] always conducted himself in a manner becoming his humble station’ and he hoped that ‘His Excellency’ would ‘take his long sentence, servitude and character into [his] benign consideration’. Cox supported his application, writing on the testimonial that Roderigo was an ‘honest and truly industrious man’ and that he ‘had never been brought before a magistrate since being in the colony’. Roderigo had also ‘by his own industry put in two acres of wheat at Bathurst’.5 His application was evidently successful, and he soon received a ticket of leave.6

Free to farm

In the general population muster of 1822 – a form of census – Roderigo is listed as ‘Landholder Bathurst’.7 His landholding was a lease of 70 acres of Crown land at Kelso ‘promised by Governor Macquarie, on or before 1st of December, 1821’.8 The land is shown on a ‘Map showing distribution of land settled by colonists’ from 1824 at plot 8 on the Macquarie River at Kelso (above). In another record, dated September 1822, Roderigo is registered as a ‘resident’ with 100 acres of cleared land, with 12 acres under wheat, ‘peas & beans’ on 1 acre, potatoes on three-quarters of an acre, and with 18 horned cattle.9 According to local Wiradyuri Elders, the area along the river being farmed by colonists, including Roderigo, was where Aboriginal people grew yams, one of their staple foods. Colonial occupation of this land compromised the local people’s access to the rich riverside soils and their yam grounds, which were soon planted with imported crops by colonial farmers.

Model citizen or recalcitrant thief?

Roderigo was an active member of Bathurst’s fledgling colonial community. In August 1822, he was listed as one of several colonists who had apprehended bushrangers in the region.10 In addition to farming his own plot as a ‘settler on Bathurst Plains’, in 1823 he was working as a stockman for William Durham.11 He was responsible for 117 head of cattle owned by Durham and another absentee cattle owner from Sydney, Thomas Hynds. A ‘Ticket of Occupation’ permitted their cattle to run on Wiradyuri land claimed by the Crown in the Bathurst area.12

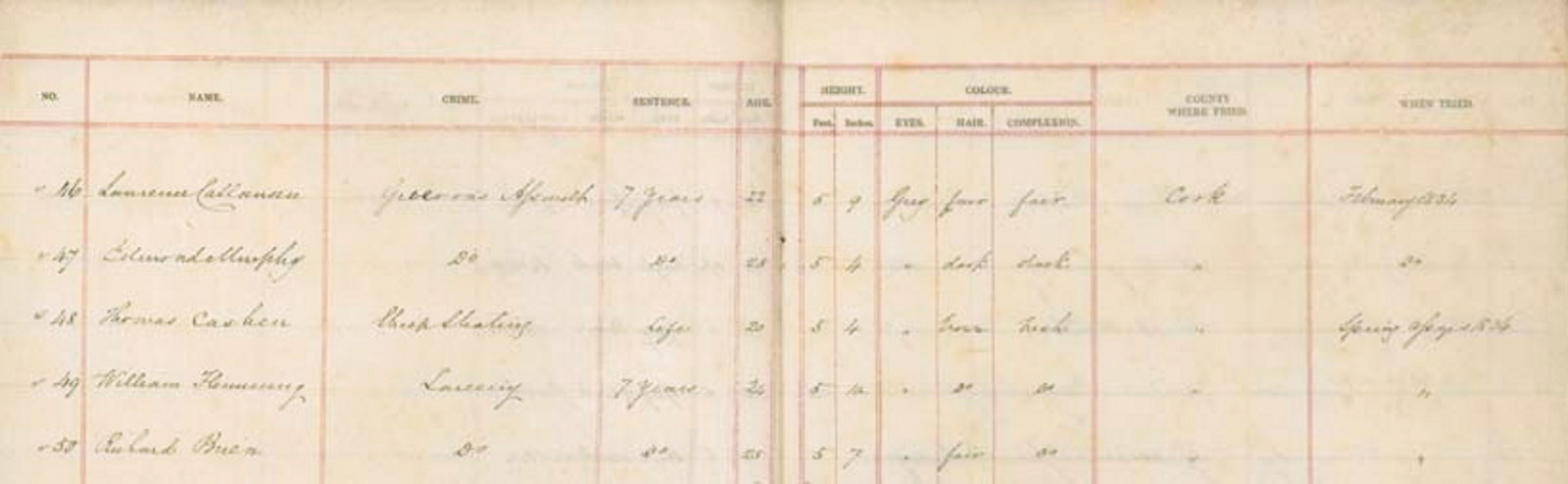

By 30 September 1824, Roderigo was described as ‘free by servitude’ – as it was now 14 years since his original conviction – however, his freedom came under threat when he was committed to court on a charge of cattle stealing.13 His name appears on ‘a return of prisoners tried before the Supreme Court on February 24, 1825’, but he was found not guilty.14

A tenuous arrangement

While the British claimed the right to assume Wiradyuri land, there was some doubt about the security of Roderigo’s tenancy at Bathurst. In 1822, he was one of several settlers to sign a memorial (plea to the governor) ‘praying that their grants be confirmed and that some forest ground be located as a common’ to provide them with access to firewood and grazing stock.15 By October 1825 he was a free man, but apparently he was not a British subject, with instructions requested from Governor Brisbane about the ‘execution of the deeds of Roderigo’s land grant, he being an alien’.16 However, it appears that he was able to continue his occupation of the land, as in 1835 the ‘estate, farm and residence’ at Kelso is listed under his name in a land grants register.17

Blood on the soil

The dispute that arose between Antonio Roderigo and the Wiradyuri in the mid-1820s over the right to potatoes is not well documented; like many other violent incidents it was not reported in newspapers. However, 60 years later, in 1886, local resident William Suttor published an account of several violent exchanges in The Daily Telegraph under the heading ‘Western Rebellions. Black v White’. His account of the intercultural conflict at Bathurst begins in 1824 with the ‘dastardly massacre’ of Wiradyuri people by Roderigo and fellow colonisers. Suttor wrote18:

In the year above mentioned a foreigner named Antonio [Roderigo] had cultivated a patch of land on the Macquarie River opposite the town of Bathurst. Among other things he grew some potatoes. One day as a large number of the black tribe of the place came by, Antonio, moved by a spirit of good nature, gave some of his tubers to those people. Next day, they having appreciated the gift, [they] appeared at the potato patch and commenced to help themselves. This was not to Antonio’s liking, who roused the people of the settlement in his be-half. They rushed down and attacked the blacks, some of whom were killed and others maimed.

The colonists’ farming activities had impinged on and potentially engulfed the local Wiradyuri people’s yam grounds, and it makes sense that potatoes would fill the role of the native tuber. The name Wiradyuri means ‘no having’, reflecting an ethos that the land and its resources could not be owned by any one person but were there to be shared. This cultural understanding of ownership would also have applied to the food growing in the soil.19

The massacre escalated the resistance movement by local Wiradyuri, who embarked on a campaign to defend their land, attacking colonists and their farms and residences, resulting in deaths among both communities.

News of the violence and destruction of farms and loss of livestock sparked fear in the colony. In an attempt to quell these increasingly violent incidents in the Bathurst region, the colonial government intervened with greater military presence and imposed martial law in 14 August 1824. When the cessation of martial law was announced in newspapers in December that year, the official proclamation stated that the local magistrates with ‘judicious and humane measure … have restored Tranquility without Bloodshed’.20 Local knowledge and subsequent recollections such as Suttor’s belie this claim, with reports of heinous incidents, including mass exterminations of Wiradyuri people, during and after 1824.21

We do not know if Roderigo had any further involvement in other conflicts. He eventually left the Bathurst district. In 1840 he gave up his land at Kelso, which was taken up by William Lee, another founding convict-coloniser of the area.22 By 1847 Roderigo was residing in the Hunter Valley, working as an ‘overseer to Mr. Hale, of Wambo’.23 On 27 January 1863, Roderigo’s application for a lease of 100 acres ‘near Hale’s 1218 acres’ was approved, at the rate of £1 per annum.24 Roderigo died two years later, in 1865, in the area of Patrick’s Plains (now the town of Singleton), aged 85.25

Truth-telling at the Hyde Park Barracks

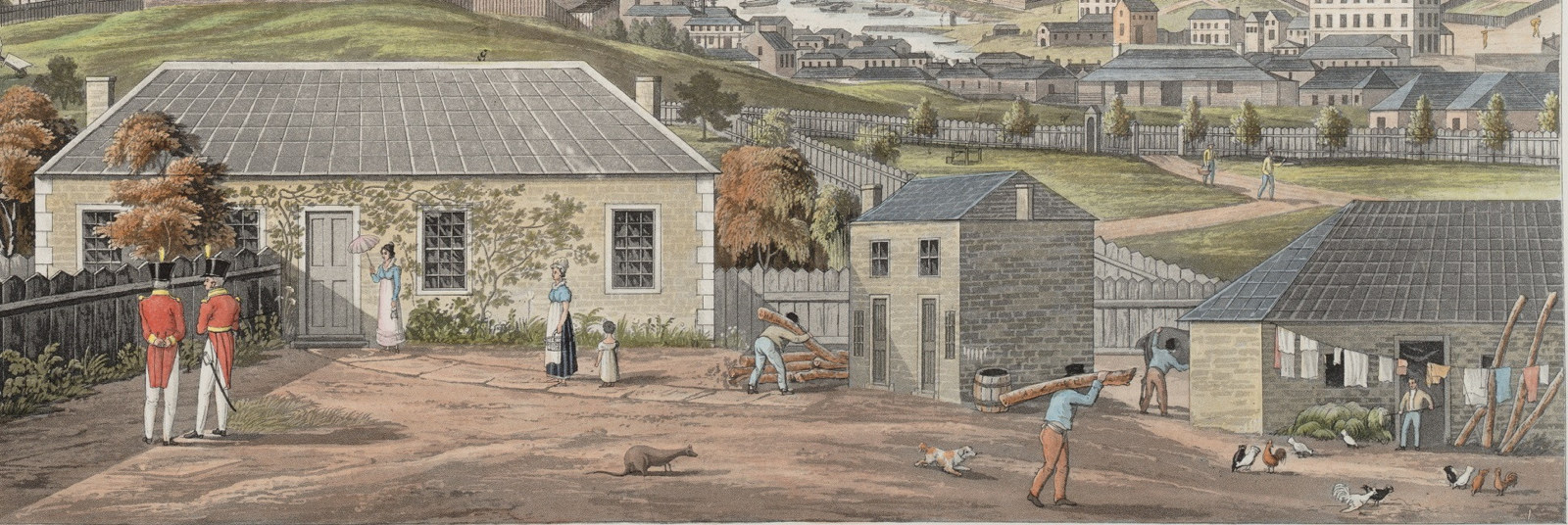

The ‘Potato Field Incident’ is one of the stories depicted in the Hyde Park Barracks’ ‘Expanding the colony’ gallery through an immersive audio narrative and a specially commissioned diorama built at 1:100 scale by Modelcraft (NSW).

Titled Dalman Ngurang (place of plenty), the diorama about the dispute between Wiradyuri people and Antonio Roderigo is one of several miniature models in the museum that were created to explore the impacts of colonisation on First Nations people. Developed in close consultation with Wiradyuri representatives from the Bathurst community, the model depicts a group of armed colonists approaching a Wiradyuri camp near a colonist’s farm. At the camp, men, women and children are gathering around a fire and foraging along the river in preparation for a meal. The rest of the story is told through the audio narrative.

This and a series of other highly detailed models are presented in an imposing sculptural shape that spans two galleries of the museum which depict convict activity in the colony.

Notes:

1. William Suttor, ‘An old story retold’, The Daily Telegraph, 23 October 1886, p9, trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/25771870. Later published as ‘Western Rebellions. Black and White’, in Australian stories retold and sketches of country life, Glyndwr Whalan, Bathurst, 1887, pp44–6, archive.org/details/australianstorie00suttiala/page/44.

2. Dhinawan/Uncle Bill Allen, a descendant of Windradyne, consultation during Hyde Park Barracks renewal, 2019. See also T Salisbury and P J Gresser, Windradyne of the Wiradjuri: martial law at Bathurst in 1824, Wentworth Books, Sydney, 1971, p22.

3. England & Wales, Criminal Registers, 1791–1892, HO 27/6, p81, National Archives UK.

4. Edna Hickson, ‘William Cox (1764–1837)’, Australian dictionary of biography, adb.anu.edu.au/biography/cox-william-1934, accessed 5 June 2024. Cox’s land is shown further along the river from Roderigo’s plot on the ‘Map showing distribution of land settled by colonists, 1824’, reproduced in this article.

5. Petitions to the Governor from Convicts for Mitigations of Sentences, 1810–1826, NRS-900-1-[4/1856], p229, State Archives Collection, MHNSW.

6. The memorial suggests the application was made in 1819, whereas a subsequent record from 1822 states that the ticket of leave was granted in December 1817: Petitions to the Governor from Convicts for Mitigations of Sentences, 1810–1826, NRS-900-1-[4/1856], p88, State Archives Collection, MHNSW.

7. ‘Roderigo, Josea A’, General Muster, 1822, Home Office HO 10/36, National Archives UK.

8. The Sydney Monitor and Commercial Advertiser, 27 November 1840, p3.

9. Land and Stock Returns: New South Wales 1818–1822, NRS 1268 [4/1231] Reel 1252, 2–13 September 1822, State Archives Collection, MHNSW.

10. Main Series of Letters Received, 1788–1826 [Colonial Secretary], NRS-897-14-[4/1761] p88, State Archives Collection, MHNSW.

11. Memorials to the Governor, 1810–1826 [Colonial Secretary], NRS-899-3-[4/1839A], File no 837, pp467–72, State Archives Collection, MHNSW.

12. Main Series of Letters Received, 1788–1826 [Colonial Secretary], NRS-897-15-[4/1798], pp123, 127, State Archives Collection, MHNSW.

13. Special Bundles, 1794–1825 [Colonial Secretary], NRS-898-33-[4/6671], p75, State Archives Collection, MHNSW.

14. Special Bundles, 1826–1982 [Colonial Secretary], NRS-906-1-[X727], p7, State Archives Collection, MHNSW; Informations and Other Papers, 1824–1947 [Criminal Division, Supreme Court of New South Wales] NRS-13477-1-[T20] 25/45 and 25/46, State Archives Collection, MHNSW.

15. Main Series of Letters Received, 1788–1826 [Colonial Secretary], NRS-897-15-[4/1798], pp123, 127, State Archives Collection, MHNSW.

16. Copies of Letters Sent Within the Colony, 1814–1827 [Colonial Secretary], NRS-937-1-[4/3515], p393, 27 October 1825, State Archives Collection, MHNSW.

17. Notices of the Intention to Issue Deeds, NSW, Australia, Land Grants, 1835, NRS-1229, Series: 1233; Roll: 1439, p332, State Archives Collection, MHNSW.

18. Suttor, The Daily Telegraph, 23 October 1886, p9. trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/25771870.

19. Dhinawan/Uncle Bill Allen, a descendant of Windradyne, consultation during Hyde Park Barracks renewal, 2019.

20. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 16 December 1824, p1.

21. Salisbury and Gresser, pp31–3.

22. The Sydney Monitor and Commercial Advertiser, 27 November 1840, p3.

23. Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, 30 October 1847, p2.

24. Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, 14 February 1863, p6; Empire, 29 January 1863, p6.

25. NSW Births, Deaths and Marriages, 5426/1865. Antonio Josea Roderigo is not to be confused with Joseph Roderick or Roderig, who lived in the Hunter area in the early 1860s and is listed in the Maitland Mercury for various misdemeanours.

Published on

Read more

Browse all

Expansion

Convicts played a crucial role in the new colony’s rapid spread, which dispossessed and displaced Australia’s First Peoples, and indelibly altered their lands

Convict Tickets of Leave

Convict discipline depended not only on punishment but also on incentives and rewards. Governor King introduced the ticket of leave system in 1801

Convict transportation to NSW

A history of convict transportation to New South Wales and related records such as trial records and records of the voyage and arrival

Convict Sydney

What was convict assignment?

‘Assignment’ meant that a convict worked for a private landowner