Books of lost emotion: exploring our historic house libraries

The thousands of books in MHNSW's historic houses provided entertainment, education, moral improvement and spiritual sustenance – and now offer intriguing and moving insights into the people who owned them.

How often have you found yourself in someone’s house perusing their bookshelves? Many of us are reading more on electronic devices than ever before, but the habit of judging people by their books persists. Shelves of books in a living room or hallway are, paradoxically, not only public but also intensely private, revealing the inner workings of the minds of a household.

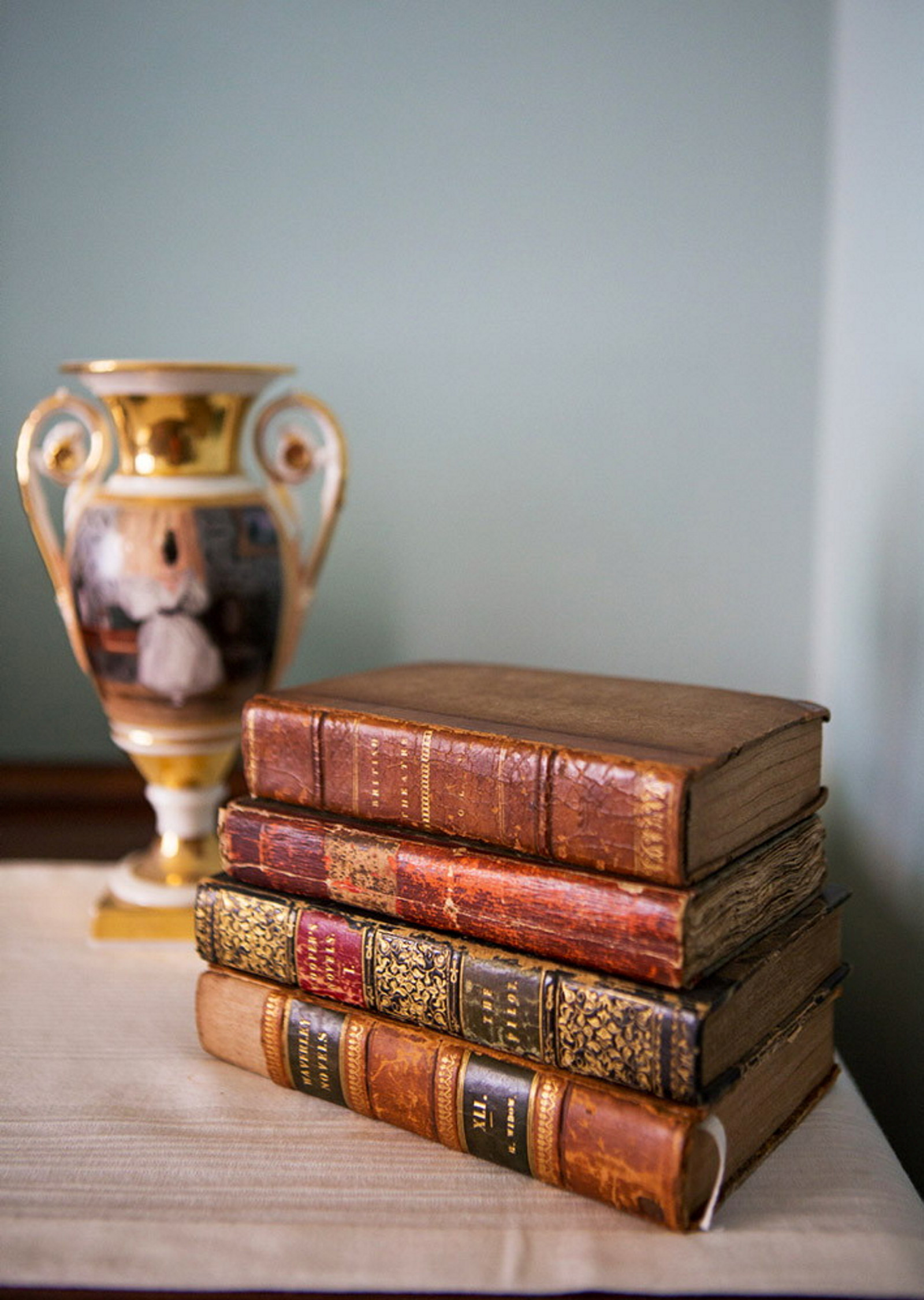

Books in the homes of the past can be similarly useful for exploring a family’s psychological make-up, but we need to apply different methods to understand what we see. Often the titles on the shelves are unknown to us, most of the authors are a mystery, and once popular subject areas can look dull to the modern reader. While these libraries may seem difficult to interpret now, their very opaqueness underscores the ephemeral nature of our own popular culture.

A world of books

MHNSW is privileged to care for several remnant historic libraries dating from the 19th and 20th centuries. Some of the libraries remain in their original home, such as at Meroogal and Rouse Hill Estate, while others, like the collection from Throsby Park, are stored in MHNSW’s Caroline Simpson Library. More challenging to interpret are the books dispersed from houses like Elizabeth Bay House, Elizabeth Farm and the small terrace houses at Susannah Place.

One of the great pleasures of exploring historic house libraries is to take them on their own terms. If we try to understand a library’s contents as an expression of multiple moments in the life of a household, often over generations, we can step into a world of books that will not only echo our own experiences but also reveal differences. We can discover popular authors of the past, learn how books were promoted and distributed in NSW, and see how they were used and valued by their owners.

To better understand an old house library we need to look beyond the printed texts and consider these libraries as a collection of objects. Can you see bookseller labels, owner’s bookplates or signatures and inscriptions on the endpapers? Marginal notes and insertions such as bookmarks, letters, drawings and pressed flowers can all add to our knowledge of a book and its owner.

Practical, prestigious and poignant

In most Australian households, books were sprinkled through the living areas, bedrooms, schoolrooms and offices, depending on the size of the house and the purpose of the books; dedicated rooms designed to accommodate libraries appear in only the largest of Australian homes. In the late 1830s, Alexander Macleay, Colonial Secretary of NSW, built a grand room large enough to store more than 4000 books at Elizabeth Bay House. A collection unrivalled in Australia, Macleay’s natural history literature and insect specimens had long been the envy of fellow naturalists in Britain. Over the next 60 years, books flowed in and out of the library – some were sold, new additions came with Macleay’s son and nephew, others were removed to England as an inheritance, and finally, in 1891, the scientific collection was bequeathed to the Linnean Society of New South Wales. Although it was later dispersed by the Society, many titles have survived, and almost 300 volumes were returned to Elizabeth Bay House in 2016.

The Macleay family’s treatment of its library over two generations suggests a practical and unsentimental approach to a collection that was valued primarily as a research tool. By contrast, the book collection of the Throsby family at Throsby Park, Moss Vale, was increasingly revered by successive generations. The earliest Throsby family members had rarely bothered to sign their books, but by the 1890s ‘Throsby Park Library’ had been scrawled inside many of the volumes. Two works in the collection were written by the family patriarch, John Throsby, and reflect the dynastic power of books. The books, Select views in Leicestershire (1789) and The history and antiquities of the ancient town of Leicester (1791–93), were probably brought to NSW by John’s son Dr Charles Throsby in 1802. An illustrious second copy of Select views, formerly belonging to gothic novelist Horace Walpole, was purchased by the family some time after it was auctioned in 1842. In 1934, a great-great-nephew of John Throsby, Dr Herbert Throsby, proudly displayed the family’s copy of the History of Leicester before the Historical Section of the British Medical Association while presenting a paper on his distinguished ancestors.

The ownership marks of multiple generations can reveal the value, utility and emotional engagement a single title can hold over many years – such as the scientific books from Elizabeth Bay House signed by Alexander Macleay, his son William Sharp Macleay and nephew William John Macleay. A copy of The miniature language of flowers (1865) at Rouse Hill Estate is signed by Kathleen Rouse; decades later, a signature has been added by her great-nephew John Terry. Perhaps most poignant is a dictionary from the Youngein family, tenants at 64 Gloucester Street, Susannah Place. On 15 April 1914, 13-year-old Dolly Youngein inscribed her signature on the endpaper of a new copy of Blackie’s standard shilling dictionary, one of the few books in the family’s possession; the children relied on weekly visits to the city council library at the Queen Victoria Markets to catch up on their reading. Above Dolly’s signature, the names of her brothers, Jim and Jack, have been added, while the name of her son, ‘Jack C Brown’, born in 1923, is inscribed at the top of the page.

The inner lives of book owners

While possession of a book may offer a clue to the interests of its owner, there’s no guarantee that the book was ever read by them. The discovery of inscriptions, notes, underlinings and inserted items offers the potential to uncover further meaning. The endpapers of a copy of The works of Alfred Lord Tennyson: poet laureate (1882) at Meroogal are laden with additions: lines of inked verse weave around dried flowers, strands of hair, and newspaper clippings. Its owner, Euphemia ‘Effie’ Leslie, used the Tennyson publication as a place to memorialise the marriage and death of her friend Jessie Billis. On one of the endpapers Effie has pressed a floral keepsake from the 1886 wedding of Jessie to Robert Taylor Thorburn, of Meroogal. She notes the date of the marriage, and pastes in the newspaper notice. Among the verses she has added is a line from ‘Human life’ by Samuel Rogers: ‘While, her dark eyes declining, by his side moves in her virgin-veil the gentle bride’. The full poem explores the transience of life, and another line reads, ‘and such is Human Life; so gliding on, it glimmers like a meteor, and is gone!’1

The pasted-in newspaper notice of Jessie’s death, less than two years after her marriage, reveals the purpose of the page. The flowers are both wedding posy and wreath. This memorial is perhaps further complicated by Effie’s own marriage to Jessie’s widower, Robert Thorburn, almost two decades later. Was Effie’s documented joy and then grief for Jessie complicated by her feelings for Robert? Maybe these emotions came later. Books from a historic house library can mean so much more than the words printed in them.

Note

- Samuel Rogers, Human life: a poem, John Murray, London, 1819, pp9–10.

Related

Published on

Related

Browse all

The Astor, 1923–2023

Upon completion in 1923, The Astor in Sydney's Macquarie Stree twas the largest reinforced concrete building in Australia, the tallest residential block, and this country’s first company title residences

City of Gods, my early experience and toy boat

Inspired by a watercolour of the ruins of the temple of Vishnu, refugee curator in residence Jagath Dheerasekara writes about Devinuvara as a site of pilgrimage, colonisation and uprising

Watch pockets

Watch pockets hung on the head cloth of a four-post bedstead and originally served in place of bedside tables, which were uncommon in the 19th century