Q&A: Jonathan Jones

The artist’s major new installation at the Hyde Park Barracks inspires visitors to consider the dual history of this important site.

A member of the Wiradjuri and Kamilaroi nations of south-east Australia, Sydney-based Aboriginal artist Jonathan Jones works across a range of media, from printmaking and drawing to sculpture and film. He creates site-specific installations and interventions into space that use light, subtle shadow and the repetition of shape to explore Indigenous practices, relationships and ideas.

Jonathan has been commissioned to create a site-specific installation that explores the history of the Hyde Park Barracks site within a contemporary framework. untitled (maraong manaóuwi) merges the visually similar symbols of the emu footprint and the English broad arrow. Both symbols talk to specific cultural ideas, reflecting two different narratives embedded in the one landscape. Thousands of the symbols, created in crushed stone sourced from Wiradjuri Country in NSW, have been laid out in the courtyard to frame the building. At the heart of the project are questions around how we construct history, how we live with history, and how history overlaps and speaks to different communities in different ways.

Your work explores cultural and historical relationships. What inspires you to tell these stories?

A lot of elders will tell you that you can’t move forward without knowing your past. Their words highlight the importance of knowing where we’ve been and where we’re going, and often ground my work. Unfortunately, Australia has yet to heed this advice and come to terms with its extraordinary past. We are the world’s oldest living culture yet we fail to look after our country. The results are mass extinctions, fires raging uncontrollably and droughts that have seen rivers fail. If we continue down this path it’s hard to imagine a future for the next generation.

Through a constructed national agenda we’ve been conditioned to understand Aboriginal and non- Aboriginal relations as a ‘them and us’ scenario, which has further distanced our relationship to Country. My work tries to draw awareness to the past so that we can have a future, one where Aboriginal knowledges are central to all our identities, and we don’t see ourselves as either them or us.

As an Aboriginal person, how do you feel when you visit a site like the Hyde Park Barracks?

Sites like the Hyde Park Barracks are complex, often undefinable, but always inspire inquiry. The convict story is significant, but where does it sit within the bigger Aboriginal story or immigrant story? Who are we telling our stories to? How can we tell our stories better?

I acknowledge that a site like the Hyde Park Barracks represents many things to many people, but we often don’t appreciate the different ways people interpret these sites. Information is today often given to us in small, uninspiring and authoritative bites, which never capture the rich complexity resting in a site and in the memory of our community. People can then feel left out and become uninterested. This project seeks to capture some of that complexity and in doing so broaden the audience’s engagement, creating a more inclusive site.

What are the elements you consider with site-specific work?

I try to consider everything. Being site-specific, in its true sense, is like a Welcome to Country. It’s about acknowledging the past, the present and the future, in order to create a holistic picture. I’m interested in understanding cultural connections and how Country informs place. By drawing out these connections we can get a better understanding of sites and create works that belong nowhere else but there. A project working this way often makes sense to the audience, as it speaks clearly to Country and contributes to the site’s memory.

How does the symbol chosen for the Hyde Park Barracks reflect the site’s dual history?

The project looks at the similarity of maraong manaóuwi, the emu footprint, and the English broad arrow. Both shapes have been etched into local Sydney rock, in a statement of ownership and demarcation.

Emus and their footprints have been slowly scored and rescored into sandstone outcrops and platforms since time immemorial, marking significant areas, events and people. The broad arrow, commonly used on colonial convict items, was also used in surveying roads and property and has been carved onto sandstone blocks, boulders and outcrops. The emu footprint and broad arrow occupy the same space but have their own unique interpretations. They become a framework through which to understand the complexities of Australian history.

What’s the importance of the emu in Aboriginal culture?

Within most Aboriginal communities the emu is highly significant. It’s one of the few animals whose father rears the young. After the mother lays the eggs, the father takes on all the parental responsibilities until the young emus can fend for themselves. In this way, the emu is an important role model for Aboriginal men, as it speaks to community aspirations of strong values around fatherhood.

The emu has become an important animal in Australian culture, being most apparent on the national crest (on the Supreme Court, visible from the Hyde Park Barracks site), but the emu’s cultural connections have been forgotten. Although the emu has become extinct around Sydney, its meaning and role in community are alive in stories and actions.

How do you imagine visitors will interact with the installation?

The artwork is created to be walked on, a process that will see it slowly destroyed. This process means the entire work will become a public performative act. The intentional destruction of the artwork questions the validity of memory, our own individual roles in history, and how we select and preserve cultural sites. Over time, the crushed red and white stones will be mixed together and the courtyard will appear as it did before. In effect, this major cultural performance will be a cycle of destruction and regeneration that will live on in our memories.

Related installation

Past exhibition

untitled (maraong manaóuwi)

In February 2020, Sydney-based Wiradjuri/Kamilaroi artist Jonathan Jones presented his site-specific installation 'untitled (maraong manaóuwi)' at the Hyde Park Barracks

MHNSW and Jonathan Jones would like to acknowledge and thank the following supporters who have assisted this project:

- Josh Black and Lucy Greig

- Penelope Seidler AM

- Glenella Quarry

- The Medich Foundation

- Neilson Foundation

Author

Ashlie Hunter, former Producer, Public Programs, Hyde Park Barracks

Published on

Related

![Pencil drawing of Bathurst 1818, Plans of Government Buildings at Bathurst, Main series of letters received [Colonial Secretary], 1788–1826.](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/zl9du87e/production/ec5b53147e75bdc6536c142340cae04b71adc992-3203x1998.jpg?fit=max&auto=format)

Convict farmer Antonio Roderigo and a ‘dastardly massacre’

A dispute over potatoes farmed by convict-settler Antonio Roderigo was one of many hostile events between colonists and Wiradyuri people that led to the Bathurst War of 1824

First Nations

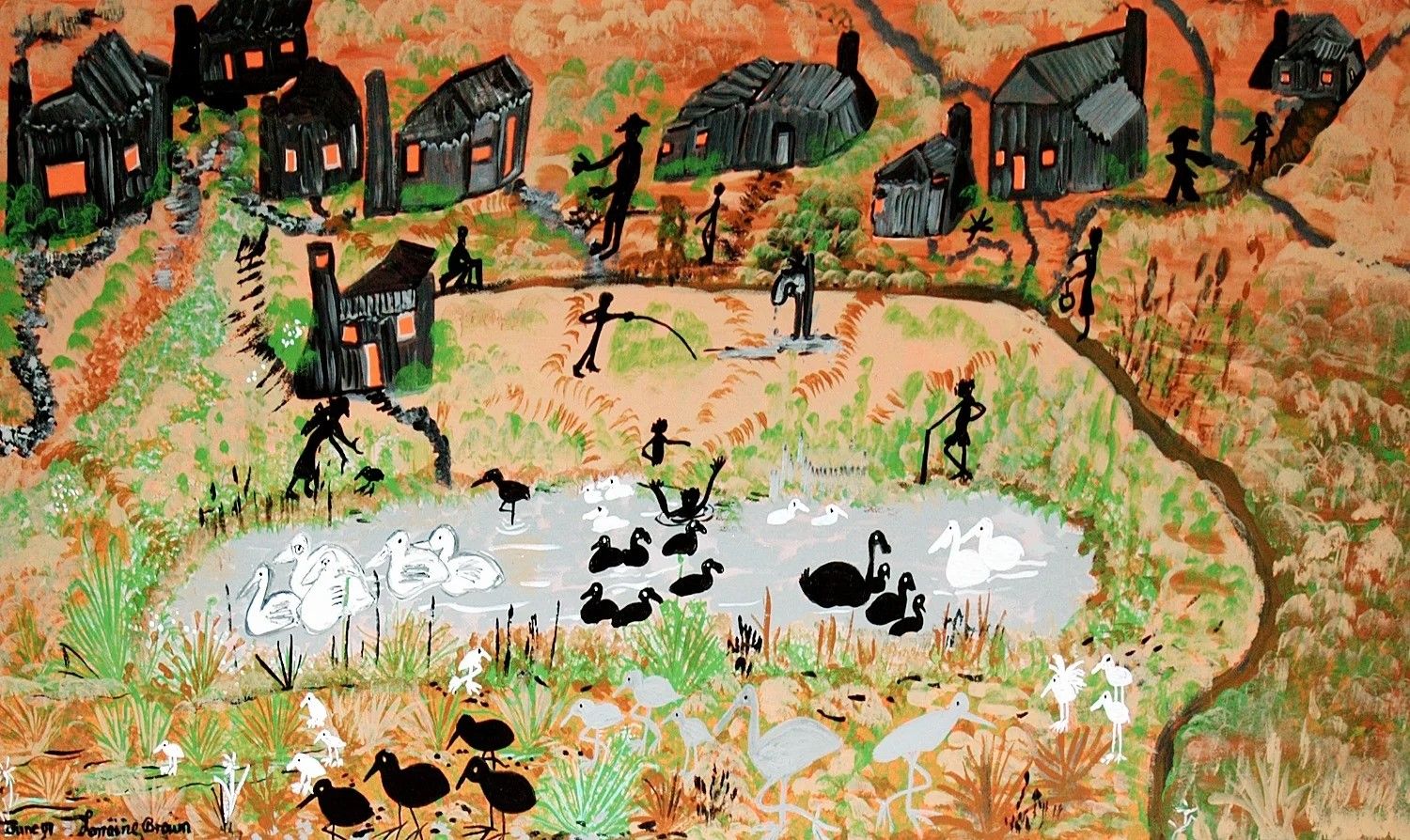

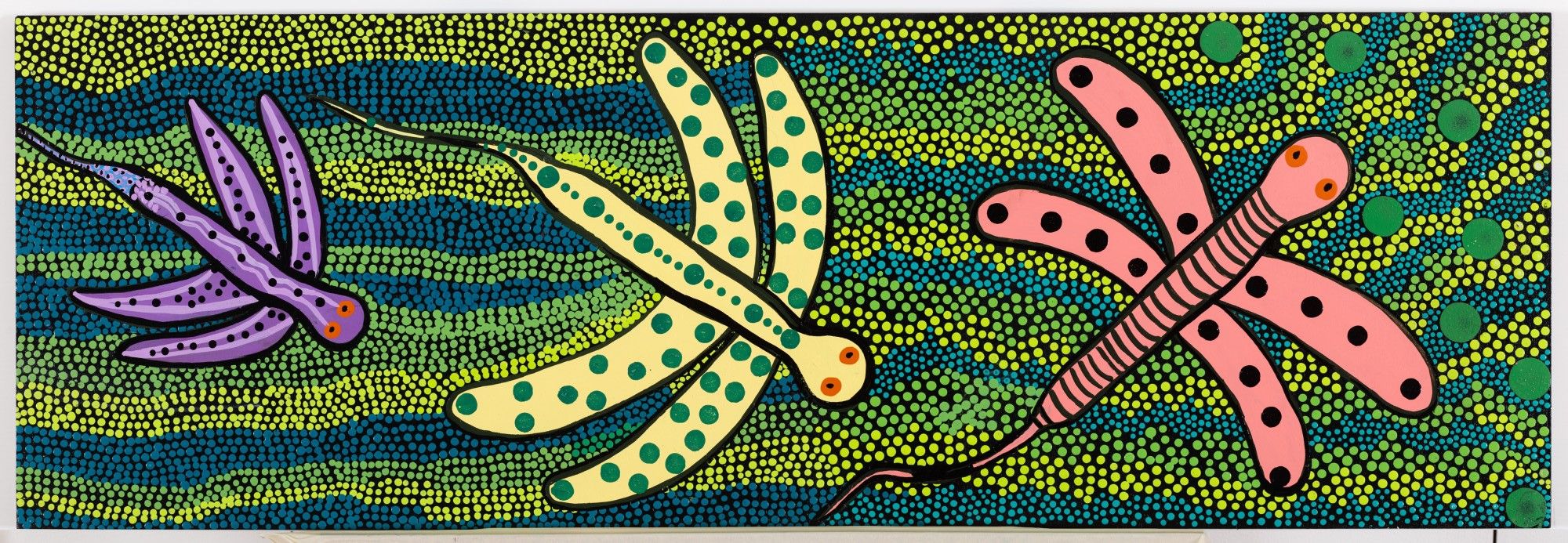

Coomaditchie: The Art of Place

The works of the Coomaditchie artists speak of life in and around the settlement of Coomaditchie, its history, ecology and local Dreaming stories

First Nations

Coomaditchie: Of place

These works record the extraordinary arc the artists of Coomaditchie have travelled over more than three decades

First Nations

Coomaditchie: Lagoon stories

These panels detail the ecological life in and around Coomaditchie Lagoon