The Mint project: Sydney’s adaptive reuse triumph

Sydney’s urban landscape is a testament to both the city’s rich history and examples of forward-thinking vision. Among the most compelling examples of this fusion of past and future is the revitalisation of the Mint complex. Completed in 2004, the adaptive reuse project centred on the transformation of the historic Sydney Mint site, on Gadigal Country, and represents a sophisticated blend of heritage preservation with thoughtful contemporary design.

It was the first project to simultaneously receive the Australian Institute of Architects’ Sir John Sulman Medal for Outstanding Public Architecture and the Francis Greenway Award for Conservation. The Mint was also awarded the Lachlan Macquarie Award for Heritage and nominated in the UK’s Building Services Journal as one of the ‘top 30 ground-breaking buildings of the world’.

Twenty years later, as a significant heritage site, a public space and a place of work, The Mint remains an exemplary model of adaptive reuse, demonstrating how heritage structures can be revitalised to meet contemporary needs while maintaining their historical integrity.

A glimpse into history

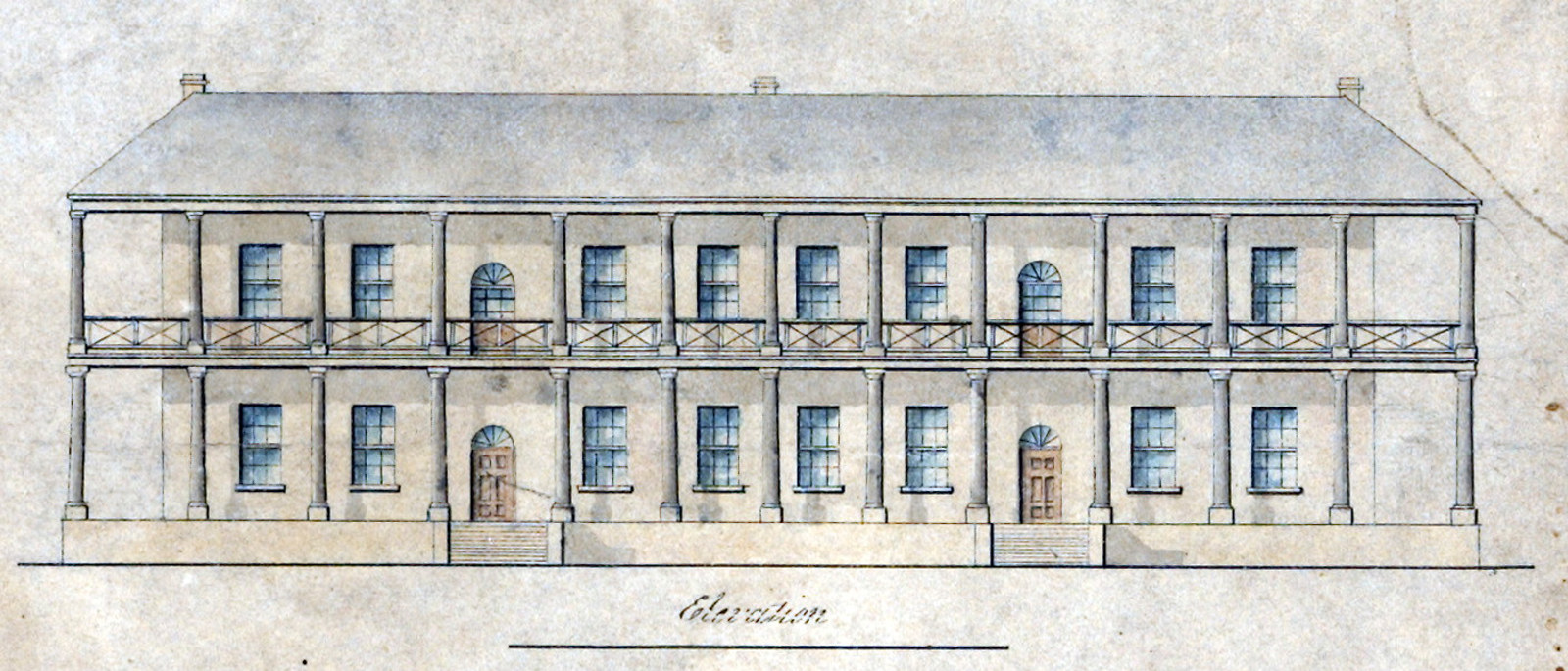

The Mint complex, situated on Macquarie Street, is a cornerstone of Australian architectural and economic history. Completed in 1816, the earliest building on the site was originally part of Governor Macquarie’s three-wing General ‘Rum’ Hospital and provided accommodation for assistant surgeons, and later a dispensary and infirmary for the poor. In 1855 it began a new life as the offices of the colony’s official Mint – the first overseas branch of the Royal Mint in London. This saw the expansion of the site with the addition of industrial buildings behind the former hospital building, including the coining factory. Coining gold and silver, the Mint played a crucial role in the early economy of NSW.

The Mint eventually closed in 1926. Over the following decades, the complex of industrial coining factory buildings at the rear of the former Rum Hospital survived repeated calls for their demolition and plans to improve Macquarie Street and erect new public buildings on the site.

Thanks to the adaptive reuse project, first considered in late 1999, today The Mint is the proud home to one of Museums of History NSW’s two head offices, as well as the Caroline Simpson Library, the Bullion Store and cafe, and a spectacular series of venue hire spaces.

The vision for adaptive reuse

Adaptive reuse is a strategy that involves repurposing old buildings for new uses while preserving their historic value. In short, adaptive reuse is futile if it fails to protect a building’s heritage values. The most successful adaptive reuse projects are those that respect and retain a building’s heritage significance and add a contemporary layer that provides value for the future.

The Mint adaptive reuse project exemplified this approach, transforming the historic coining factory buildings into modern, multifunctional spaces without compromising the site’s heritage significance. Integrating new technologies and functionalities while preserving the site’s character required careful planning, innovative design solutions and precise execution.

The project team consisted of the architectural firm FJMT (now fjcstudio), with heritage consultant Clive Lucas & Stapleton, and keen involvement from Peter Watts, the then director of the Historic Houses Trust of NSW (now MHNSW). The result attests to the collective team’s skill and dedication to achieving a harmonious balance between historical integrity and contemporary relevance.

The project’s objectives were clear: to preserve historical elements, integrate contemporary functionality, promote commercial and environmental sustainability, and enhance public engagement.

Preserving historical elements

Unsurprisingly, one of the project’s central goals was to retain the industrial buildings’ original architectural features. The project focused on peeling back layers of 20th-century additions to reveal the 19th-century spaces, fabric, patina and overall industrial quality of the place. The project reopened numerous original doorways, windows and skylights and revealed an extraordinary assemblage of prefabricated iron components, as well as deliberately exposing the two sandstone spine walls running the length of the coining factory to illustrate the richly layered evidence of past uses – including the grit and texture of the minting processes, and mid-20th-century court and office adaptations – along with decay and neglect.

An archaeological program was undertaken by Godden Mackay Logan (now GML Heritage) as part of remediation works on contaminated land which revealed wall footings, machinery bases, hearths and underground flues. All these elements were fully documented and recorded; some were incorporated into the design of the new office spaces, others preserved under new additions and features, and the installation of services was carefully planned around all remaining elements.

Modern functionality

The project introduced a range of flexible spaces, such as multipurpose event spaces, exhibition areas, office and administration spaces for staff, and modern amenities. All spaces were designed to be both adaptable and discreet, and new interventions were cleverly chosen to complement rather than overshadow the historic fabric. These included the addition of a sleek modern atrium with glass walls and roof which offer a contemporary counterpoint to the historic stone and provide natural light and visual connectivity between different parts of the former industrial complex. Warm timber was also chosen to complement the tones and materiality of the stone used throughout the complex. Other new additions included glass partitions and modern lighting fixtures that provided a contrast to the traditional elements while enhancing functionality.

The project included the installation of thoughtfully designed ramps and elevators to improve accessibility; these modifications ensured that the complex became welcoming and usable for all visitors while maintaining its historical layout. These upgrades have made the Mint complex a dynamic, accessible venue for various activities, from cultural events to educational programs.

Sustainable design

The 2004 project integrated sustainable design practices reflecting a visionary consideration of a building’s environmental impact. These included the installation of energy-efficient systems such as LED lighting; high-performance heating, ventilation and air-conditioning systems; and water-saving fixtures. Considered material choices and conservation strategies were integrated to reduce the building’s environmental impact; materials used in the new additions matched those employed in the historic structures in terms of thermal performance (meaning how well a building retains heat). Roofs, both old and new, were also given improved insulation. This reduced the need for a large-capacity air-conditioning system and reduced the stress placed on the historic fabric by fluctuating conditions.

The use of sustainable materials and technologies has minimised the building’s environmental footprint while preserving its historical attributes and leveraging the embodied carbon of the historic complex, demonstrating incredible foresight and ingenuity in relation to issues emerging in sustainable heritage conservation practice today.

Community and cultural impact

The revitalised Mint continues to serve not only as a head office for MHNSW but also as a cultural and educational hub, hosting a variety of events, displays and programs that engage the public and foster a deeper appreciation of Sydney’s heritage. Visitors can explore the site’s rich history while enjoying contemporary amenities and events. The Mint’s role as a cultural venue fosters a sense of community and pride in Sydney’s cultural landscape.

Looking ahead

Twenty years on, the Mint project stands as a landmark example of how historic buildings can be successfully adapted with sensitivity and creativity. Through a thoughtful architectural approach that prioritised understanding of the place’s significance and integrated preservation with innovation, the project revitalised The Mint, ensuring its continued relevance and accessibility today and for future generations. It serves as an inspiring model for similar projects around the world, demonstrating that with careful planning and design, the old and the new can coexist harmoniously. Projects like this one continue to play a crucial role in demonstrating that innovation and preservation of heritage are not mutually exclusive.

The Mint adaptive reuse project was more than just a renovation; by blending historical preservation with modern functionality, it still offers a blueprint for how owners of heritage places can honour a place’s cultural significance while advancing into the future.

Published on

Read more

Browse all

Unexpected views

Over the decades, photographers have captured unexpected glimpses of the Mint’s history

Museum stories

The changing face of the Mint

As photographers documented the evolving face of the Mint, they recorded changes to the site and streetscape

After the Royal Mint

Between 1926 and 1997 almost 20 different government departments and law courts came and went from the Mint buildings

Francis Greenway: the ‘future safety’ of the Rum Hospital buildings

When Sydney’s Rum Hospital was completed in 1816, the buildings were already showing signs of potential collapse, but newly-appointed Civil Architect Francis Greenway came to the rescue