From the collection: staff favourites

We invite staff to write about their favourite object from our collections.

Choosing just one piece from the vast array of objects we care for has proved a challenge! Joanna Nicholas and Mel Flyte have selected intriguing and beautiful items from the Vaucluse House collection, objects that are fascinating in their own right but also personally evocative. A killer’s name scrawled in a notebook, and a record of a sailor’s life: curators Nerida Campbell and Anna Cossu chose objects that reflect the storytelling power of our collections.

Stitching, making, mending …

Joanna Nicholas, Regional Coordinator

One of my favourite Hans Christian Andersen stories as a child was about a darning needle who ‘thought herself so fine, she imagined she was an embroidering‑needle’. The moral of the story was lost on me at the time, but the image of the proud needle was significant because my earliest memories are of my mother sewing and embroidering. I remember her beautiful hand movements and the sound of the needle being tugged through the cloth. She’d learned these skills from her mother and paternal grandmother; the latter made her own hats and gloves, sewn with the finest, tiniest stitches. I still have one of the first things my mother made for me – a velvet dress pocket embroidered with a butterfly.

I think this is why Sarah Wentworth’s Dutch cast‑silver chatelaine resonates with me so much. Sarah (1805–1880), the daughter of ex-convicts, was apprenticed as a milliner before she married William Charles Wentworth. They went on to have ten children, and made their home at Vaucluse House. It’s thought that the chatelaine was acquired on their travels to Europe in the 1850s when they were living in England.

The chatelaine consists of six chains with appendages mostly for needlework – a penknife, scissors in a scabbard, a pincushion, a thimble in its holder – as well as a heart-shaped vinaigrette for holding smelling salts, and a pencil.

I imagine that Sarah, like my mother, was deft with a needle. I’m not an embroiderer, yet, but I can dream.

Pass the salt!

Mel Flyte, Collections Discovery Assistant

This silver saltcellar was probably purchased by the Wentworth family on one of their visits to Europe. It’s such a whimsical object. Imagine sitting down at a grand dinner, asking your host to pass the salt, and seeing this little chariot race down the table bearing its savoury cargo. What a treat!

Saltcellars are documented from as early as Roman times, and became increasingly elaborate through the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance. One large cellar was placed on a table, either close to the lord or host or in the centre to be shared. By the 19th century, individual cellars had become popular, corresponding with changes in dining fashions. By the 20th century, their use was in decline with the advent of non-clumping table salt and the salt shaker.

My mother bred Arabian horses, and I’m often drawn to equestrian objects and images. I’m always reminded of a Bedouin legend that speaks of Allah taking a handful of the southerly wind to create the horse, a creature destined to fly without wings and conquer without swords – much like this little steed.

I also love all things blue, so the only thing that could make this object more special would be if it still had its original cobalt-blue glass liner, which protected the silver from the corrosive effects of salt.

A matter of identity

Anna Cossu, Curator

Stained and worn, this identity card travelled the world with Norwegian sailor Arnt Martinius Andersen, known as Martin, more than 100 years ago. This simple document reminds me of my own grandfather, who emigrated to Australia from Italy around the same time as Martin, in the early 1920s. Both were seamen who for reasons that remain elusive ‘jumped ship’ in Australia and established new lives in Sydney.

Martin was a resident of Susannah Place from the mid-1930s until 1963, and much of what we know about him comes from oral history interviews with his sons, who knew little of their father’s early life. This identity card issued in the French port city of Rouen contains multiple purple-inked stamps for the ports Martin passed through during 1918–19. More evocatively, it also holds a small passport-style photograph of the 29-year-old Martin and records the tattoos inked on his body – a cross and the words ‘In memory of my dear mother’ and ‘True love’. My grandfather also had tattoos from his seafaring days, though in later life he kept them hidden beneath his shirtsleeves.

In 1939, following the outbreak of World War II, and ten years after these identity papers were last stamped in France, Martin presented them once again to the authorities. Like all immigrants and residents who weren’t British subjects, Martin was required to register as an ‘alien’ at his local police station. As for his earlier French identity documents, his photograph and fingerprints were taken. Although my grandfather had been naturalised in 1927, he was still subject to some of the wartime ‘enemy alien’ regulations.

Devotion to duty

Nerida Campbell, Curator

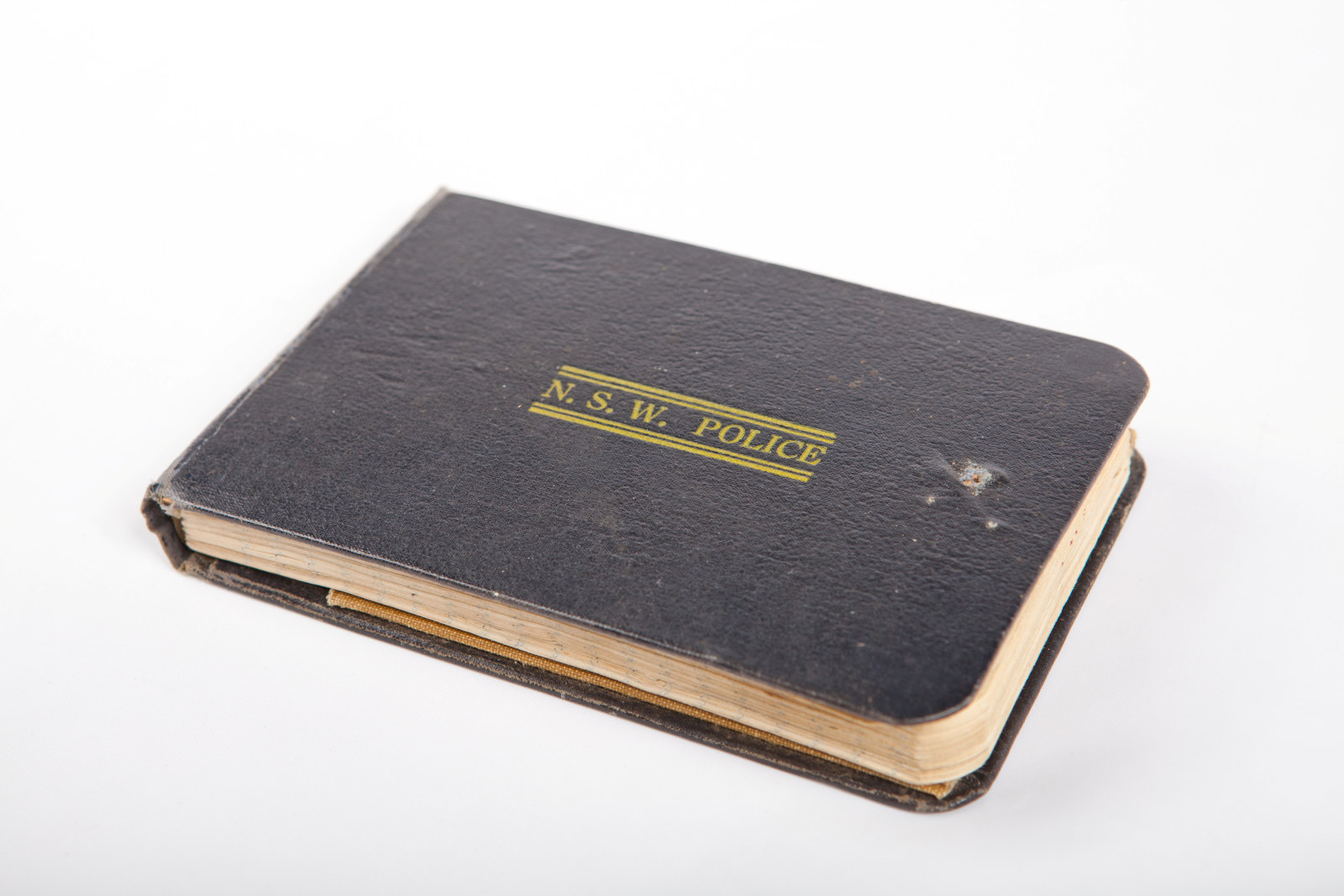

This notebook from the Justice & Police Museum collection always gives me goosebumps. The courage and devotion to duty shown by its former owner, Constable Cyril Howe, still inspire awe among those who hear his story. Every time I see the notebook I reflect on the risks faced by police daily.

In 1963, Howe was based at the Oaklands Police Station in southern NSW when he pulled over a car driven by William Stanley Little, who was suspected of stealing cheques and a shotgun from his employer. When Little attempted to escape, Howe gave chase, and Little crashed his vehicle. Howe again approached Little, who shot him in the stomach. The constable retreated to his police car as the two men exchanged fire, before his police‑issued pistol jammed, leaving him defenceless.

As Little got away, taking a hostage with him, the mortally wounded officer wrote the shooter’s name repeatedly in his notebook. He was found alive but in immense pain, and his initial concerns were to give a full report to a fellow officer, ensure his pistol was safely secured, and communicate instructions for his funeral. Howe, aged 31 and a father of three, died shortly afterwards. He was posthumously promoted to the rank of sergeant.

Published on